Rugby law changes: Why the 50:22 trial will not necessarily mean more kicking

The mission statement as World Rugby confirmed the global implementation of 50:22 law trial from August 1 was simple:

To encourage the defensive team to put more players in the back-field, thereby creating more attacking space and reducing defensive line-speed.

“Welfare benefits” were cited as a potential consequence, but the tweak could certainly alter the tactical landscape of rugby union.

The 50:22 law sees a side throw into a lineout if they kick the ball indirectly into touch beyond the opposition 22 from behind the halfway line. This strike from Alex Lozowski, playing for Montpellier against Leicester Tigers in the European Challenge Cup final last season, was one of World Rugby’s examples:

Being awarded a throw into a lineout from here would have been an excellent, possibly game-changing result for Montpellier.

To combat it, Leicester might have dropped right wing Kini Murimurivalu deeper in order to help full-back Freddie Steward cover the back-field:

Consequently, their midfield defenders might have had to drift laterally rather than pushing up aggressively. Leicester’s players might have opted against competing at the previous breakdown in order to maintain as much width as possible in the front line.

Crucially, the introduction of the 50:22 – which will not affect the British and Irish Lions tour, only competitions that begin after August 1 – will not necessarily mean more kicking. The intention is that rewards for certain kicks change the behaviour of defences and create more space.

Creating space

Crowded defensive front-lines, comprising 13 or 14 players with two or even just one man covering the back-field, have been in fashion for most of the past decade. Scott Sneddon, now head coach of Loughborough Students, used to be the attack coach for South China Tigers, Global Rapid Rugby’s Hong Kong-based team.

Speaking last year, he said that the 50:22, which was trialled in 2020 and adapted from the 40:22 law in play the previous season, caused an immediate rethink. Global Rapid Rugby 2020 only got through a single round, on March 14, before a coronavirus suspension. Even so, Sneddon noticed patterns.

Need more rugby action? 🏉🏉

Catch ALL the full game replays ➡️ https://t.co/sVe9dFIFRs #RapidRugby pic.twitter.com/VuirPVapzY— Global Rapid Rugby (@rapidrugby) March 15, 2020

During their 52-27 victory over Manuma Samoa in March last year, South China Tigers amended their defensive formation.

“We were still seeing sides defending with a back two,” explained Sneddon, a Welshman who moved to Hong Kong after a spell as a player-coach at Rosslyn Park.

“But they were going slightly wider, leaving the middle of the field completely open. A lot of teams play with a back two. Depending where you are on the field, they will be close to the 15-metre lines. Now they’re sitting 10 or five metres from the touchline.

“That gives you a load of space down the middle of the park. We didn’t think we could allow opponents that much space, so we trialled having our nine almost halfway back in the middle of the field with our back two sitting almost 10 metres from an edge.

“Scrum-halves will usually stand in the line and be a shooting threat or even just an extra number filling in at guard. We trialled it that maybe he could stand in on a ‘half’ – as a winger might do but in the middle of the field. He would be in a position to cover the back-field down the middle if needed, if he saw the opposition 10 drop into the pocket. If there were any chips or dinks, he would still have the ability to work in behind.

“We caught Samoa long down the middle of the field a few times and they didn’t catch us once. This may have been down to our scrum-half putting them off the long midfield exit. Samoa tried a couple of kicks to compete, our scrum-half managed to cover up any high balls in that area. With the extra man on a half we felt quite comfortable because it gave us an additional man to work with our kick-counter.”

This illustrates how South China Tigers altered their defensive set-up in open play, moving from a 13-2 formation to a 12-3 or ‘12-2½’:

Ian Prior, a versatile half-back who has represented Western Force in 2019 and 2020 Rapid Rugby tournaments as well as the 2019 NRC and Super Rugby AU in 2021, went further.

“On the defensive side, you have to be wary of [the 50:22],” he said, before outlining another layer of deception. “But you can also lure the other team into [kicking] if you play quite shallow with two at the back. Then it becomes a bit of a race to see who can execute their skills better.”

Essentially, the cat-and-mouse relationship between kicking and back-field coverage, which often sees wide passing to coax defending wings up from deep positions and manipulate space in behind, remains. Only the stakes are higher.

“The kick can give you a 60-metre net gain and it’s your ball, too,” added Prior, who notched up a number of 50:22s in a victorious 2019 NRC campaign for the Force. A strong driving maul was one of their chief weapons.

“A lineout in the opposition 22 can be a game-changer in terms of momentum. I think it’s a great rule. Even if it’s one defender you take out, it still opens up a great deal of options.”

In breathless Rapid Rugby, which did not allow the ball to be kicked out on the full at all, the significance of a 50:22 is mitigated by another quirky law. Attacks that begin behind a team’s own 22 and travel all the way up to the opposing try-line can yield nine-point tries. Under regular laws, even without that bonus, Sneddon predicts a fascinating trade-off.

“If they have two in the tackle and two and a half in the back-field, there is going to be space. From the point of view of an attack coach, it would promote playing to that space a little more.

“From a defensive point of view, coaches will still say: ‘Right, if they want to run it back, let’s kick and put the emphasis on our chase and keep them back there’.”

When are 50:22s happening?

Last year, South China Tigers’ playmakers sat down to theorise about 50:22s. Turnover ball was the first area they identified as a chance for game-changing strikes.

England have been extremely effective themselves when kicking in these transition situations. Take this try, set up by Owen Farrell and scored by Jonny May against Wales in 2018…

…or this one against France a year later. Just 14 seconds span between Tom Curry and Courtney Lawes forcing a tackle-turnover and May dotting down from Elliot Daly’s grubber:

Yet another similar finish from May arrived at Rugby World Cup 2019. Henry Slade sets it up:

Scrums were also brought up in South China Tigers’ meeting. In the middle of the field, deploying a kicker at first-receiver on either side of a set piece can cause serious headaches. Prior has accomplished a 50:22 for Force after shuffling away from his number eight and receiving a pass from the base.

“With a four-two defensive set-up, you often need a full-back to cover the whole field, unless they go with two back – and if they do that there are obviously opportunities to get gain-line success there.”

He had more ideas concerning phase-play.

“The other option from scrum-half was to go against the grain with a ‘toppy’, when the ball bounces and gets a bit of a roll after their wing has come up a bit early and becomes disconnected from their full-back.”

South China Tigers did not manage any 50:22s against Manuma Samoa in 2020. They could, and perhaps should, have had three. This was one passage from which they might have capitalised.

It begins as Manuma Samoa clear from their own 22:

South China Tigers gather and run the ball back:

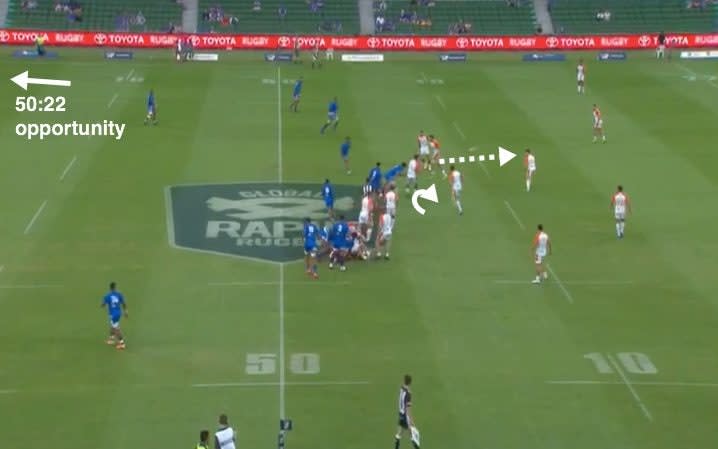

Their counter is initially stopped just before halfway, meaning a 50:22 is in play on the next phase over towards the far touchline, Manuma Samoa’s back-field coverage is slightly confused and shallow.

South China Tigers identify this, so after a flat first-receiver steps up…

…a swivel-pass gives a playmaker time:

The kick aims to find space and bounce into touch beyond the 22…

…but is mis-hit and stays in-field:

The 50:22 is sure to alter the mundane kick-tennis rallies that punctuate every professional match. It might gradually eradicate them.

A version of this analysis was first published in 2020

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport