Arlott and Swanton embraced change while still keeping cricket’s soul intact

A prelude to summer arrived last week, and with it a noisy chorus of speculation over the future of cricket. A posh boy – Tonbridge and Peterhouse – with a faith in statistical analysis became the chief national selector of an unsettled England team. Cries of dismay greeted the revelation that the new inter-city competition will be based on yet another shortened form of the game, this one requiring each side to face a mere 100 balls in order to fit television schedules. And the BBC was outbid by a commercial rival for the radio rights to an overseas Test series.

Once again the most serene and timeless of games was being tossed and buffeted by those who cannot leave it alone. Or so it seemed. But perhaps the best way to put all this into some sort of context is to read a new dual biography of a pair of famous cricket writers and broadcasters whose views and voices became synonymous with the game in the second half of the 20th century. Under the title Arlott, Swanton and the Soul of English Cricket, the historian David Kynaston and the journalist Stephen Fay demonstrate that most of these arguments have been going since anyone now alive was old enough to roll the dice in a game of Owzthat.

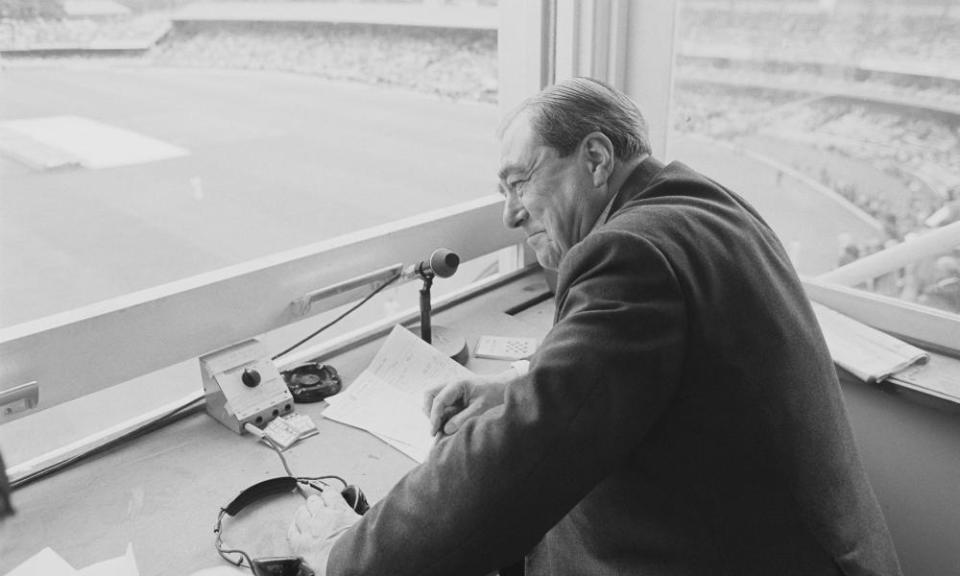

On the surface, John Arlott and EW “Jim” Swanton were such different types that it would be easy to set them up as opponents in a permanent battle for the game’s imagined soul. In the press box Arlott represented the Guardian and Swanton the Telegraph, with all the attendant contrasts of attitude and tone. In the broadcasting booth they were similarly divergent, Arlott’s increasingly wine-darkened Hampshire burr lovingly taking its time over describing the small, seemingly peripheral details of the unfolding drama, while Swanton’s close-of-play summaries were delivered in a crisp, forcefully judgmental style, as if a man in an MCC tie had suddenly emerged to address the multitudes from the Vatican balcony.

In the endlessly recurring debate over the England captaincy, one of them could be expected to root for Yorkshire’s pragmatic Ray Illingworth, the other for Kent’s patrician Colin Cowdrey. While one encouraged the formation of the first cricketers’ union and became its honorary president, the other helped establish an annual competition for the old boys’ sides of leading private schools.

It would be easy to fall for the caricatures of the chippy liberal and the pompous snob. But Kynaston and Fay look deeper, recognising that if Swanton imagined himself to be, in the words of one exasperated England tour manager, the Lord Protector of English Cricket, while Arlott’s radio audience saw him as a poet laureate of the eternal game, they shared a devotion to its welfare which expressed itself not in a defensive conservatism but in a commitment to changes that both saw as inevitable.

The authors admit to having begun their project as “Arlott men”, which is perhaps how a fair proportion of those reading this would categorise themselves. Arlott wrote beautifully, as befitted a former producer of poetry programmes for the BBC, his view of the game characterised by its empathy for the journeyman professional. By contrast Swanton’s prose never rose above the functional, a vehicle for the ex cathedra pronouncements with which he expected to mould opinions at breakfast tables from St John’s Wood to the shires.

But if they were never likely to be friends, they shared a position on several important matters, none more vital than the question of English cricket’s response to the growing worldwide protests against apartheid. In Swanton’s case, tours to the West Indies and South Africa had modified what might otherwise have been his caste’s standard views on questions of race.

In this of all weeks it is worth recalling his reaction to Enoch Powell’s “rivers of blood” speech, which he called “hateful, lacking a single compassionate phrase towards fellow members of our Commonwealth” and “a complete negation of patriotism”. This came in the midst of the debate over whether England should select Basil D’Oliveira, a refugee from the apartheid regime, for a tour of South Africa. On that one, Swanton and Arlott – who had been suspended from the BBC’s Any Questions in 1950 for describing the South African government as Nazis – were united.

It’s easy to stub one’s toe on an ingrained prejudice against Swanton and his assumed omniscience. The man who thought amateurs made the best captains also voted to accept women as members of his sacred MCC, while he and Arlott both gave their blessing to the introduction of one-day competitions.

I finished this fine book in the Oval’s Bedser stand, while watching the first day’s play in the County Championship match between Surrey, the county of Peter May, an England captain who habitually sought Swanton’s advice, and Arlott’s beloved Hampshire. Apart from the helmets, the numbers on the players’ shirts, the fielding side’s huddle before each resumption, the floodlight pylons and the swooping canopy over the Vauxhall End stand, surprisingly little seemed to have changed in the game since their heyday.

What would they have thought of the Moneyball-style data analytics that Ed Smith will apply to the business of selecting an England team, or of the furore over the ECB’s 100-ball version of Twenty20? In the end, perhaps the headlines are best seen as a demonstration that people still care about cricket and want to help it navigate a safe course through a rapidly changing world, just as it has done ever since attendances at County Championship matches began falling in the 1950s. The arguments over how to avert cricket’s death might just be the real signs of its life.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport