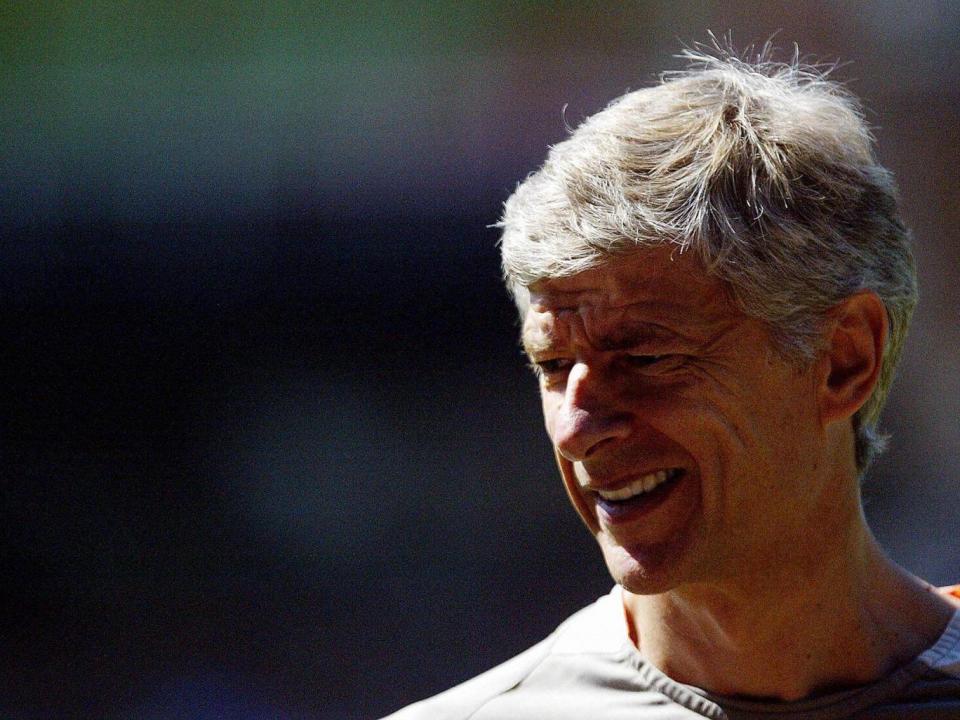

Arsene Wenger: Philosophy, politics and parents - 'Le Professeur' opens up on life at Arsenal

Among the nicknames attached to Arsène Wenger when he arrived at Arsenal, with his stopwatch, studious air, and what Tony Adams called "his boffin's glasses", was Le Professeur. Little did Adams, Paul Merson and company know that, 12 years on, the French academic would be engaged in one of football's most audacious experiments, with their club as the guinea pig.

When Arsenal committed themselves to moving from Highbury early this decade Wenger decided to embark on a bold, some would say suicidally naïve, venture.

In a rare interview this week he revealed: "When we decided to build the stadium I wanted to anticipate the possibility of financial restrictions, so I concentrated on youth. I also felt the best way to create an identity with the way we play football, to get players integrated into our culture, with our beliefs, our values, was to get them as young as possible and to develop them together. I felt it would be an interesting experiment to see players grow together with these qualities, and with a love for the club." He pauses, smiles wryly, and adds, "It was an idealistic vision of the world of football."

This credo, which has never previously been expressed so clearly, has provided Arsenal fans with both delight and frustration. There is pride among supporters at the club's development of young players, and joy at the football they deliver, but there is also frustration at the lack of trophies. The investment in the Emirates was supposed to provide Arsenal with the financial muscle to compete with Chelsea and Manchester United in the transfer market. According to the recently departed director Keith Edelman it has. He said there was £70m available to Wenger. If there is, it sits in the bank, gathering interest. Another transfer window is about to close and Wenger, as usual, looks like roughly breaking even.

Last week he said he could spend £30m on a player if he wanted to, but he does not need to. Results this season will demonstrate whether that is the case or not, but the reality is Wenger does not want to. This visionary is a stubborn one. The board would clearly give Wenger whatever he asks for, even if it stretched the finances, but the economics graduate will only ask for £30m in extremis. Nor is he about to countenance a £135,000-a-week contract even if Mathieu Flamini and Alexander Hleb have departed for better paid employment elsewhere, and Emmanuel Adebayor was evidently tempted to follow.

Wenger believes his team are already good enough to win one of his two targets, the Premier League or Champions League, but feels they will not peak for five or six years. "The challenge we face is to keep them together," he admits. "It is very important to meet their needs inside the club, the way we play, the way we behave, with success on the field and in financial rewards. If you can achieve that as a club you can keep them together. I don't feel at our club you have to make any other sacrifice than financial, because all the other aspects are better at our club than anywhere else."

The financial sacrifice is, however, non-negotiable. "I believe you need a wages structure," says Wenger, "if you want to be fair with everybody, or try to be as fair as possible. You could make the odd exception but you need a logic in the way you pay your players and in the way you structure the whole wages bill. Personally, I don't think it is right to lose £100m and to play football. I feel that the skill of a manager is to do the maximum with the resources he has and try to be successful. I don't believe that [£100m losses] can last a long time, it will not be accepted, not only because it will implode [if the benefactor pulls out]."

"If you do not balance the books you go bankrupt and die. I could push the club into big debt. I go away with success and the guy who comes after me suffers for five years because he cannot buy a player any more and the club goes down. The guy who comes after me has good players he can work with, he has a healthy financial situation, and he has a club in good shape. That is part of management as well."

Elite footballers, obviously, already earn more than any normal person can spend but the same applies to stars in the financial world. In football, as in the City, the biggest pay packets are not about spending power but parity.

"It is more a status thing than the actual money," says Wenger. "The player compares himself to other players he thinks are on the same level, not because of the money, more for the respect for his own quality. That is where meeting their needs comes in. Money is only one fraction of the needs that a player has at a club. On that front you can sometimes accept a small disadvantage knowing that the rest is superior."

Wenger has done this himself, rejecting offers from clubs such as Real Madrid and Barcelona because he believes his working conditions at Arsenal could not be bettered elsewhere.

Only Sir Alex Ferguson's tenure at Old Trafford now exceeds Wenger's at Arsenal and, like the Scot, Wenger has steeped himself in, and deliberately abided by, the culture of the club.

"I feel if you come into a club as manager you have first to work out its specific qualities," Wenger says. "For me Arsenal is a club which tries to respect tradition, style, honesty, fair play. If you come in and behave like a gangster you will not last long. The supporters will be the first ones not happy with that. A club needs values. If a club has no values you go nowhere."

Wenger's own values come from his parents, Alphonse and Louise, who ran an auberge in the Alsace village of Duttlenheim when the young Arsène was growing up. "Everyone is an extension of their parents," he says. "When you are very young you do not feel that the influence of your parents or your education is decisive. The more you grow into your maturity you realise you feel you are only comfortable with yourself if you are respecting the values you got when you were a kid. It takes you some time to discover that. You feel independent, but when you look back at your life you find that what guides you is the values you got when very young. Then you accept it.

"A trait of my parents I recognise in me is the belief that you work very hard and you shut up. If you are good someone will see it. You try to do as well as you can and, if you are honest and you work hard, you will be all right."

We are speaking on an afternoon when Wenger's faith in such natural justice has taken a blow. Together with Cesc Fabregas, Manuel Almunia and Faye White, the captain of Arsenal Ladies, Wenger has been touring the Young Persons Unit at University College Hospital, London. It is a prime example of the facilities developed by the Teenage Cancer Trust, which has been chosen by Arsenal this year to be their club charity. The unit, from which Arsenal's Emirates Stadium is visible, is exclusively for teenagers and Wenger has been taken aback by the sight of so many sick youngsters. Cheerful as many appear in front of the Arsenal party, whose visit hugely overruns such is their popularity, their baldness - the cruel imprint of chemotherapy - reveals their true condition.

"Personally, it is a shock," says Wenger. "When you are used to seeing teenagers together in good health, to experience them together like this is difficult to take. You do not expect them to be sick.

"What is very impressive is the team attitude to fight against cancer. The children are brought together, the parents are brought together. What comes out of that unit is, 'Let's fight it together'." Wenger inevitably recognised parallels with the mood in a successful squad, the same sense that, he says, "You can be stronger together."

Wenger places great store by team spirit; it is one of the benefits he hopes to realise by building a club from the youth ranks. Maintaining it, however, requires a constant vigil.

"You check that every day that the team is bonded. You try always to make sure it is integrated. It is never guaranteed, and it is very fragile and vulnerable. It can be upset by exterior factors or interior factors and can disintegrate very easily. It is the skill of the manager to always assess it and to address the situation when needed. A team is made of a collection of individuals. Sometimes a few individuals feel they do not need to put their energy into the team as much, and think more about themselves. That quickly has consequences for the team."

Once Wenger balanced his squad between what he described as "an English block and a French block". Now his squad features 17 nationalities but there is one dominant accent. The French core grew to six leading players with the acquisition of Mikaël Silvestre. Is that a risk? "It is natural the same culture gets together. If you yourself met some English people in Jamaica you will speak to them, you will have dinner together. You cannot fight against that because it is a lost fight. If you have a dinner together you will choose the same kind of food. It is a glue, it is part of you. What you can fight for is to keep the communication going inside the team and make sure this does not go into a clique situation."

The decline of "the English block" has been endlessly commented upon and, when pressed, Wenger addresses the subject wearily. Yet while it is true that high hopes are being expressed for the rising generation of Jack Wilshere and Henri Lansbury, not forgetting Theo Walcott, it is only four years ago he sang the praises of Ryan Garry, Justin Hoyte and Ryan Smith. All have since left the club.

"They were victims of the competition. It is not a question of nationalities. The Premier League today is a competition among the players of the whole world; at the top clubs it is a competition among the top players of the whole world. Of course that is detrimental to some English players and it will be tough for Wilshere and Lansbury, but if they make it they are world stars and you do not have many world stars in any academy, not now you can only recruit locally."

In assessing a player Wenger says he looks for "intelligence, motivational level and talent". The first criterion would, to many cynics, rule out most English players but Wenger insists they were not lacking in this area. He admitted they may seem under-educated compared to foreign players, not least because the English are inordinately impressed by anyone who speaks more than one language, but adds, "Don't worry, the big players in England are intelligent."

Maybe we just start too late. In his first job, as a youth coach at Strasbourg, Wenger began taking a class of five-year-olds. The club academy began at seven. At the time English clubs were not allowed to access children until they were 14. After a few years the two groups in Strasbourg were compared. The class which began at five had developed a technical advantage, says Wenger, which could not be bridged. "You have to pause every 20 minutes as they cannot keep a longer focus, but the big row in the Olympics, about the gymnast who they said was only 12, teaches you at 12 you can be technically at the top level in the world."

But I ask, speaking as a father of a five-year-old, what can I teach him at that age? "To kick correctly the ball. To put him in situations where he develops his skill. The talent of a coach is to put an exercise to a player that he has to find the solution to. If he does not, you teach him to do it better. If the exercise is too easy, or too difficult, he will not learn. And he has to find it out for himself. What makes football special is you have a billion techniques. It is not like in tennis where you hit the ball." Wenger demonstrates a low forehand. Then, with more demonstration, he adds, "In football when you come to hit the ball you have someone pushing you on the top of your left shoulder, and you still have to keep your balance and hit the ball right. At the start your basic movements have to be right, then you adapt."

The first time I sat down with Wenger, 11 years ago, he was still new to the capital and I wondered what he had seen of one of the world's great cities. He said he knew only the journey to Heathrow, to Highbury, and the training ground. I remind him of this and he smiles, almost sheepishly. "You know, nothing has changed, except the way to the Emirates is slightly different to Highbury. If someone says, 'Can you show me London?' I say, 'Buy a good guidebook and do it on your own'."

Is this sad, or admirable? What it confirms is that Wenger is one of the great football obsessives. There is this perception that Ferguson is the football nut, hewn in the tenements of Govan and honed on the terraces of Ibrox. Yet, compared to Wenger, the graduate from the Continent via Japan, Ferguson is a renaissance man, keenly interested in wine, art, the piano and horse racing.

Even with this hinterland Ferguson has found it hard to leave the game and Wenger you suspect will continue until his health gives way. Now 58, he has said he recognises the pressures of the job could cut short his life but it is a risk he will take to pursue "the only life he has wanted". He says, "Ten years ago I said to my wife [Annie], 'Five more years and that's all', and I am still here. So now I do not want to make those statements any more. I hope I will be strong enough to say one day 'that's it', but I am more focused on beating Fulham [Arsenal’s next game] than my longer future.

"I cannot imagine not working. Fishing in the morning is not so much what I like. It is a trap, this job, you are under high pressure, with big targets, but you cannot imagine not having it. That is not enough in itself, you must enjoy it. At the moment I enjoy it, I am healthy and successful, and I hope that lasts."

Inevitably the family – he has a daughter, Leah, approaching her teenage years – suffer. "It is difficult to find time to see them but there are jobs [which are worse]. You have guys who leave for work on Monday and come back on Friday. In my job I travel, but the problem is not so much the quantity of time you spend with your family, it is the quality. That is where this job is more damaging. You do not always give them the quality they deserve when you are at home because you are thinking of the next game."

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport