How Bramall Lane's occasional cricketing heritage came to an end

As Britain reels from the impact of one advisory referendum, perhaps it is a decent time to remember another, of which the result – unlike the more famous and recent example of June 2016 – was promptly and most emphatically ignored by those in a position of power.

In the winter of 1970-71 Sheffield United asked their 450 shareholders to tell them whether they wanted to see Yorkshire continue to play a few games of county cricket each year at their original home, Bramall Lane – “simply [to] give the board an idea of the temperature among the shareholders”, as the chairman Richard Wragg put it. And it was 50 years ago today that the result was announced, with the majority of shareholders happy to see cricket remain.

Related: Australia let themselves down in search of victory over India | Geoff Lemon

“In considering future policy the directors will give full consideration to this view,” Wragg said. “This just proves what a set of fools the board would have looked if they had decided to move cricket from Bramall Lane. The board will, however, continue to do what they think is best for the club. This is not a referendum, but obviously the views will be given full consideration.”

Within six months Yorkshire had been told to pack their bags. At United’s annual meeting in August, “some weeks” after the decision had been made, Wragg explained that “cricket had become an encumbrance” and “our move was expected”, with Yorkshire given an approximate timeframe of “two or three years” to make alternative arrangements. “We are not interested in having cricket at Bramall Lane because it would stop us progressing,” he said. “There is no guarantee we are going to have a good football team, but we must make the effort to have a ground fit for a good football team.”

Cricket fans would see some poetic justice in what followed: Sheffield United made their decision having just won promotion back to the First Division. Ten seasons later they had been relegated three times, to the low point of a single season in the fourth division in 1981-82. Currently bottom of the Premier League with two points from 17 matches, this is their seventh top-flight season in 44 and is looking increasingly like their last for the time being.

It is not hard to see United’s motivation, however, given they had been playing in a three-sided stadium, with the cricket square stopping construction on the fourth touchline, restricting attendances and income, for the sake of four county fixtures a year plus a bit of Yorkshire League action. Talk about the end of cricket at the ground had occurred for nearly a century, since the 1870s when clubs using the ground in the summer had repeatedly been forced to find alternative venues so that Bramall Lane could be used for bicycle races. Notably in 1898, when the Sheffield Evening Telegraph debated ideas for the redevelopment of the ground, they factored in “a very fine oblong cycle track all round the ground”.

In 1961 rumours of cricket’s imminent end forced United’s then chairman, HB Yates, to put out a statement “to allay the anxiousness which is bound to be felt by the cricket-loving public, not only in Sheffield but all over the world” insisting “the subject has never at any time been discussed by the board”. There is a slender chance this was not a fib.

And then there was the state of the wicket. In 1893 Alfred Pullin, better known as Old Ebor, wrote “there is no mistaking the fact that the Sheffield wickets are not fit for first-class cricket”, adding: “The wickets have not been good there for some years. Such a state of things is hardly creditable to a first-class ground. The circumstances may be exceptional, but I know that some Sheffielders have strong doubts as to whether a good wicket will ever be possible again at Bramall Lane.” As controversy over the state of the square continued over the next decade it was widely accepted that pollution from nearby factories made it impossible to successfully nurture grass, though the ground’s pristine bowling green made such an argument logically problematic.

But though as the years went on they only irregularly got the chance to watch the game, and even then on a dodgy wicket, the Sheffield crowd was known for being particularly knowledgable about and passionate for the game, if a little more vocal than others – in 1938 the Guardian wrote about “spectators of the usual Bramall Lane breed, howling at times like young lions after their meat”. And they got to witness more than their share of history and drama. There was the time in 1877 when a batsman hit a shot, ran two runs and, on returning to his crease, exclaimed: “Now, you can’t do that,” and promptly died (the deceased, Joseph Parker, was perhaps not at his physical peak, being as he was 53, and a joiners’ tool-maker by trade).

In 1935 Jock Cameron, the great South African wicketkeeper who was destined tragically to die of typhoid within six months, hit 30 runs off a single Hedley Verity over (one of the balls he hit for six was found the following May, lodged in a rainwater spout in the pavilion). Geoff Boycott hit his first century for Yorkshire there, and Herbert Sutcliffe his 100th. England played Australia there in 1902, the ground eventually becoming one of only two venues (after the Oval) to host both a Test and an FA Cup final. In 1949 Denis Compton, fielding for Middlesex, was bitten by a small black dog that had run on to the pitch.

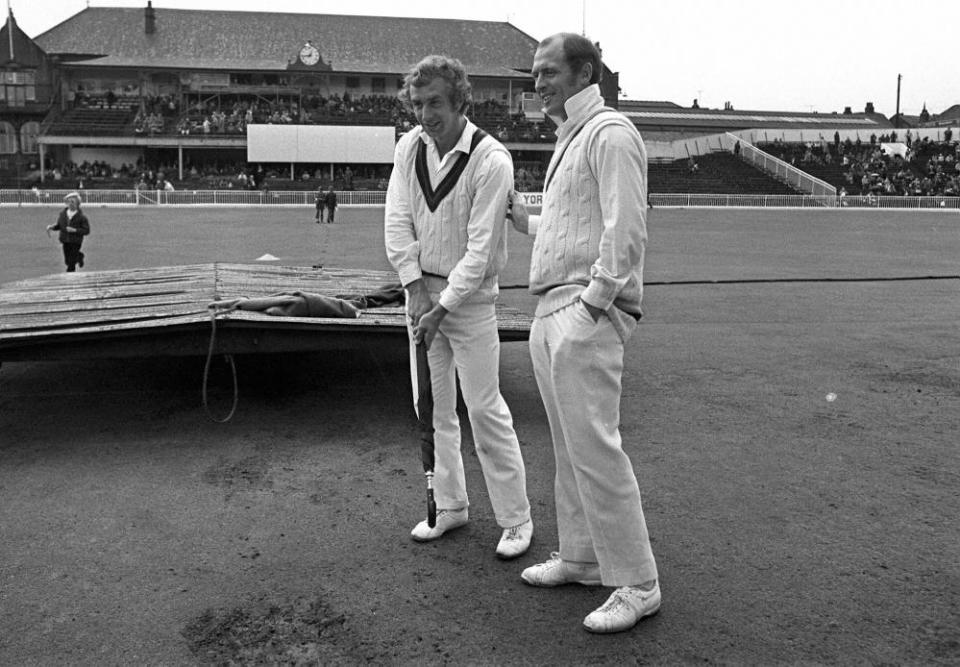

Yorkshire played there for the last time in 1973, a game against Lancashire which was, perhaps inevitably, rain-affected and meandered to a draw. The square was dug up and sold to fans for 20p per square yard, and work on the new stand that was to cover it started within a week. A year later it was reported “it is still not definite what will happen to the cricket pavilion, from which Yorkshire’s greatest names emerged each summer for an era which lasted 118 years and preceded Sheffield United’s formation by 34 years, but the choice seems to lie between a supermarket and a multi-storey car park”.

This is an extract taken from The Spin, the Guardian’s weekly cricket email. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport