Brazen, entitled, comfortable: why hot-mic debacles like Thom Brennaman's happen

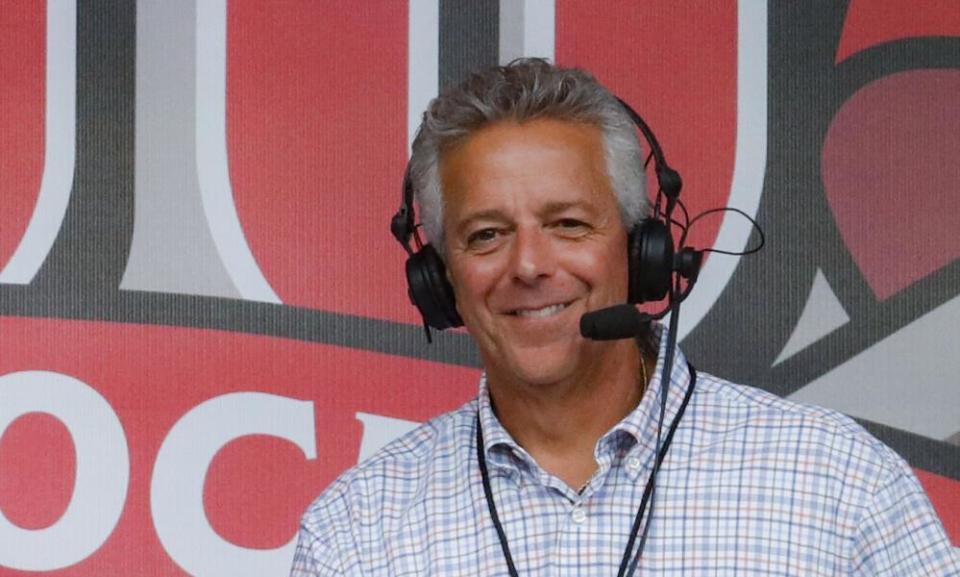

It took place coming out of a commercial break during Wednesday’s doubleheader between the Kansas City Royals and Cincinnati Reds. Thom Brennaman didn’t think anyone but Fox Sports’ broadcast production crew was listening in. But as the television voice of the Reds would discover, his audience was actually significantly larger and soon to swell well beyond the baseball world.

Related: Cincinnati Reds broadcaster Thom Brennaman uses anti-gay slur on air

“One of the fag capitals of the world” said Brennaman, with the audible swagger of a star dishing out a dose of knowledge his crew would surely be lucky to have. Not long after, some nauseating news made its way through Bernnaman’s waxy earpiece and into his soon-to-be-sizzling cerebrum: his microphone, normally turned down during breaks, was live and dangerous and shooting his anti-LGBTQ slur directly into social media news feeds everywhere.

With the aid of Fox Sports and Reds management, Brennaman somehow continued to broadcast well into the second game, despite experiencing that hot, head-spinning feeling you only get when you know you’ve really, really screwed the pooch. In the fifth inning, sensing an opportunity to make the moment worse before unceremoniously departing the booth, Brennaman managed to botch the apology.

no way did this just happen, this is not real pic.twitter.com/6ou1BkAhYW

— paco (@AllaireMatt) August 20, 2020

“That is not who I am and never has been”, said Brennaman, while pretending to be someone else other than who he really is. On Twitter, social justice champions such as Curt Schilling, who was himself just hours away from being associated with a fraud scandal, lamented the cancel culture that was rapidly overwhelming the ”nice guy” defense of the ex-pitcher.

With a good night’s sleep to think about it, Brennaman got his words together for botched apology, part two. That brought us a hilariously desperate take in which he denied knowing that the word was “so rooted in hate and violence”. Clearly the room emptied out so fast, there was not one single person left to help poor Thom.

It’s probably worth asking just what sort of work environment would make a broadcaster such as Brennaman feel comfortable enough to alienate an entire LGBTQ+ community for the intimate pleasure of his Reds broadcast team? Either it’s one that’s in on the jokes, or, maybe it’s the Ellen DeGeneres version, where easily replaceable crew members put up with a crass work environment for the credit and the check.

Of course, if you’re Brennaman, you wouldn’t so easily and effortlessly risk decades of top-tier television work without at least some sense of entitlement. As the son of Reds broadcaster Marty Brennaman, a legend who spent 46 years on the air until September 2019, he was born with a long lead off first base, broadcasting games at the tender age of 23, an opportunity that surely had nothing to do with his famous father. Later he would expand his portfolio to play calling national MLB games for Fox, in addition to NFL games. With that kind of capital, perhaps it becomes easier to believe you can say anything in the name of entertaining the crew, that is, until the booth breaks into the real world, and then, poof: even being a white male in the baseball boys’ club can’t save you.

As a one-time television co-host of MLB’s late-night, live coverage on Channel Five in the UK, I learned two things quickly. Never read anything off the prompter you didn’t approve of ahead of time, and always beware of the hot mic. Oh, and if you get caught saying anything you weren’t supposed to on air, don’t even think about blaming the techs.

I never thought that getting through dozens of broadcasts without off-mic commentary that included either homophobia or racism or sexual harassment was much of a career accomplishment, but perhaps I should have known better.

That’s because my very first job in television had involved watching live Major League Baseball games for the classic and now-defunct This Week in Baseball television program, logging the highlight worthy moments. We had clean feeds of games coming in from all over North America and, between innings, mics of broadcasters were often left on. Cameramen would often kill time by panning through the stadium stands in search of cleavage, in cahoots with commentators who offered up profound punditry on size, shape and quality. Even back then, when it seemed like you could say just about anything you liked in the workplace, and when there were far fewer opportunities for such transgressions to leak into the open, it felt like a brazen, risqué act.

Between the current leadership in the White House and moments like Brennaman brought us, it’s clear that an old-school mentality is hanging on, mostly amongst certain folks who can or think they can get away with it, even despite the ongoing movement to clean up offensive and hurtful language from our everyday lexicon. Some like the president operate in clear daylight, while others fight off politically correct fastballs in the shadows. Mostly, resistance to change seems to come from middle-aged to older white males, a segment of the population that happens to fill the majority of game calling radio and television broadcast positions. Thursday morning sports talk radio hosts in New York wondered which local broadcaster was most likely to pull a Brennaman-like blunder: all of those mentioned were white and male.

Indeed, gender and racial distribution across most major sports is heavily skewed. As of the 2018 season, 29% broadcasters were white (48 of 251) despite some 70% of NFL players being African American.

Current inequities aside, based on the full rebuke from Fox Sports, the Reds, and the overwhelming lack of resistance from the press and Twittersphere to Brennaman’s suspension, there’s reason to believe the tolerance for barefaced discriminatory language is continuing to slide. Even better, public reaction from a pair of Reds players also tells a hopeful tale of a younger generation unwilling to put up with such unbridled bias for any longer.

To the LGBTQ community just know I am with you, and whoever is against you, is against me. I’m sorry for what was said today.

— CountOnAG (@Amir_Garrett) August 20, 2020

LGBTQ+ community, as a member of the Reds organization, I am so sorry for the way you were marginalized tonight. There will always be a place for you in the baseball community and we are so happy to have you here.

— Matt Bowman (@bowmandernchief) August 20, 2020

Perhaps that’s the truest sign yet that acceptance of the unacceptable is on borrowed time.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport