Child genius Diego Maradona became the fulfilment of a prophecy

In the 1920s, as Argentina, a booming immigrant nation, sought a sense of identity, it became apparent that football was one of the few things that bound its disparate population together. No matter what your background, you wanted the team in the blue and white striped shirts to win – and that meant the way the national side played was of political and cultural significance.

The debate was played out in the pages of El Gráfico, and a consensus emerged that Argentinian football stood in opposition to the game of the British, the quasi-colonial power having largely departed by the beginning of the First World War. On the vast grassy playing fields of the British schools, football was about power and running and energy. The Argentinian, by contrast, learned the game in the potreros, the vacant lots of the slums, on small, hard, crowded pitches where there was no teacher to step in if it got a bit too rough; their game was about streetwiseness, tight, technical ability – and cunning.

Related: Diego Maradona, one of the greatest footballers of all time, dies aged 60

If a statue was to be erected to the soul of the Argentinian game, El Gráfico’s editor Borocotó wrote in 1928, it would depict “a pibe [urchin] with a dirty face, a mane of hair rebelling against the comb; with intelligent, roving, trickster and persuasive eyes and a sparkling gaze that seem to hint at a picaresque laugh that does not quite manage to form on his mouth, full of small teeth that might be worn down through eating yesterday’s bread.

“His trousers are a few roughly sewn patches; his vest with Argentinian stripes, with a very low neck and with many holes eaten out by the invisible mice of use … His knees covered with the scabs of wounds disinfected by fate; barefoot or with shoes whose holes in the toes suggest they have been made through too much shooting. His stance must be characteristic; it must seem as if he is dribbling with a rag ball.”

A little under half a century later, Diego Maradona made his international debut. Even at 16, he was not just a great footballer, he was the fulfilment of the prophecy.

Maradona, who has died aged 60, was a child of the potreros. He described himself as a “cabecito negro” – a little blackhead, the term used by Eva Perón for those of mixed Italian and indigenous heritage she saw as her natural constituency. Maradona’s parents were devoutly Peronist and had pictures of both Evita and Juan Perón on the wall at home.

His father had been a boatman on the Paraná delta in the province of Corrientes in the far north-east of the country and had moved to Buenos Aires to join his wife, who was living with relatives and had found a job as a domestic help. When the relatives moved, his father had to build his own house from loose bricks and sheets of metal in Villa Fiorito, a slum so violent that police were bussed in every day because it was considered too dangerous to maintain a permanent presence. One night, while a toddler, Maradona fell into an open cesspit. “Diegito,” shouted his uncle Cirilo as he helped him out, “keep your head above the shit.” It was a phrase Maradona would repeat like a mantra in the more difficult moments of his life.

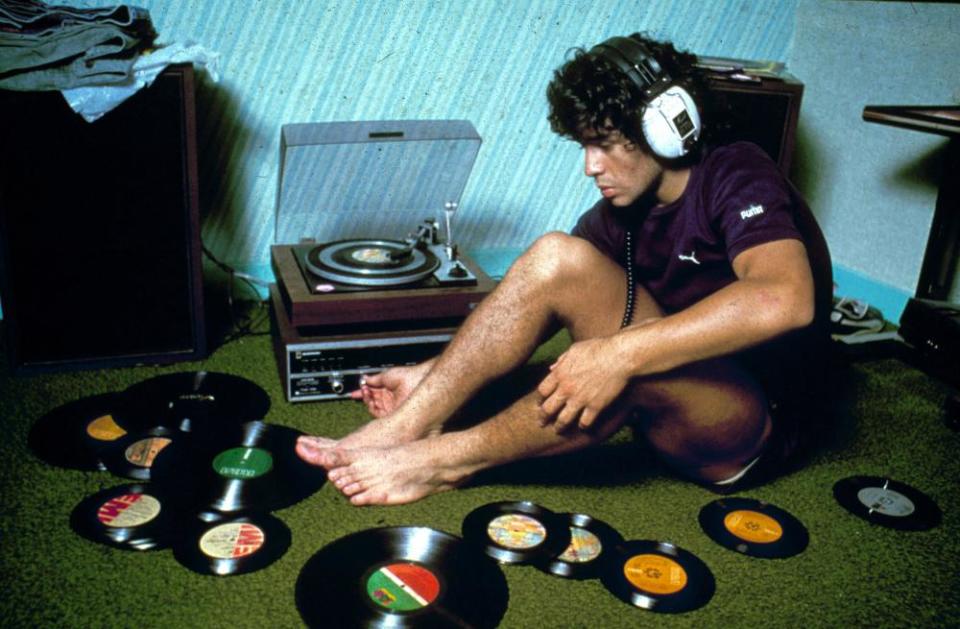

Growing up with neither electricity nor running water, Maradona made money however he could – opening taxi doors, selling scrap, collecting the foil wrapping from cigarette packets. On the way to school he would do keepie-ups with an orange, a crumpled newspaper or a bundle of rags, not letting the ball touch the ground even as he went over a railway bridge. An early photograph shows him, aged perhaps four or five, standing in front of a wire fence that is battered and twisted from how often he’d thumped a ball against it. This was the precisely the football education Borocotó had demanded.

So gifted was Maradona that when he first went to the youth side of Argentinos Juniors, los Cebollitas – the Little Onions, for a trial, they thought he must be older than the eight years he claimed to be, but malnourished. When a check of his ID card convinced them, they sent him to a doctor who put him on a course of pills and injections to build him up. Almost immediately he became a phenomenon, entertaining the crowd at half-time in league games by performing tricks with the ball. By the age of 11 he had begun to be mentioned in the national press. Expectation and a familiarity with pharmaceutical enhancement were there from the start.

So, too, was a tendency to indulge Maradona. It soon became apparent that the rules didn’t apply to him. His headmaster gave him a pass grade for exams he missed. He was a terrible loser, forever finding others to blame. He was immature and irresponsible, and laboured constantly under the demands of fans, the media and his club. After moving to Boca Juniors in 1981, the club’s financial problems meant he had to play in an endless string of money-spinning friendlies. He had more injections to help deal with the strain. The pressure became intolerable.

His cocaine abuse began at Barcelona, where he never fitted in. He was happier at Napoli, where he was the focus, and inspired them to two league titles and a Uefa Cup, but even that spell was turbulent, his performances coming against a backdrop of rumours about his drug-taking, his partying and his relations with the Camorra, the Neapolitan mafia.

Rules remained something to be got around, on the pitch and off. His handball against England in 1986 was the first of three in high-profile games: he won a penalty after handling in the 1989 Uefa Cup final and cleared off the line with his hand against the USSR at the 1990 World Cup. He evaded the drugs testers by use of a plastic penis and a fake bladder filled with somebody else’s urine. His tax affairs remained contentious for decades after he left Italy.

Eventually, in March 1991, Maradona tested positive for cocaine. He was banned for 15 months, put on weight and drifted. There were unsatisfying spells with Sevilla and Newell’s Old Boys. When journalists camped outside his house, his friends shot at them with air rifles. And yet when Maradona said he would play at the 1994 World Cup, he was welcomed.

He was not a footballer to be treated by ordinary standards. He was not merely a genius but one who came draped in symbolic importance. In his entire career, he was great for perhaps four seasons. There was nothing about him of Lionel Messi’s relentlessness; his brilliance was dredged from obvious internal struggle.

His performances in 1986 remain the greatest by any individual at a World Cup. He didn’t just score goals, he didn’t just score brilliant goals, but scored brilliant goals with gambetas, the slaloming dribble characteristic of the pibe. He had come from the potreros, he still played the game of the potreros, and he had won a World Cup by doing so; even better, he had done it against England.

Maradona remained a quasi-messianic figure. By the early 1990s, his pronouncements on a range of subjects were greeted with extraordinary reverence. In his capacity to speak to all parts of the nation he drew comparison with Perón. He was credited with powers way beyond those of any mortal. That’s why, with no managerial experience to speak of, he was placed in charge of the national side for the 2010 World Cup. It’s why there is a Church of Maradona in Buenos Aires. It’s why his fake penis was put on display at a museum in Buenos Aires like a religious relic – and subsequently stolen on a nationwide tour.

He lost weight. He gained fitness. He returned. He scored in Argentina’s first game of the 1994 World Cup, against Greece. After the second, against Nigeria, he was selected for a random drugs test. He failed. Back home, there was a mood akin to grief. Buenos Aires had seen nothing like it since the mourning for Perón. As if to confirm the link, confirmation that the B-sample was also positive came on 1 July, the 20th anniversary of Perón’s death.

He came back for a couple more desultory seasons, raged against the conspiracies that beset him and failed another drugs test, but 1994 was the true end, the end not merely of him as a great footballer, but of a great emblem of Argentina.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport