When David Beckham was the most hated man in England – and had the greatest season of his life

David Beckham looked out of the window and spotted a man staring back at him. It was late at night, and Beckham was alone inside his home in Greater Manchester. He’d been fast asleep when a loud noise outside had roused him, sending his dogs into a barking frenzy.

The man stood outside his house: arms folded, motionless, expressionless. Beckham stared at him, and he stared back – for five minutes. “What do you want?” Beckham eventually shouted out of the window. But there was no reply, the man just kept staring. At that moment in 1998, Beckham was the most hated man in England. Even in his own home, he no longer felt safe.

A few weeks earlier, the 23-year-old had been the villain of England’s World Cup defeat to Argentina. He’d stood in the car park outside the Stade Geoffroy-Guichard, sobbing uncontrollably into the arms of his father while the Argentina squad departed on their team bus, twirling shirts above their heads in celebration.

For Argentina, the next stop was a World Cup quarter-final with the Netherlands. For Beckham, what lay ahead was the most challenging 12 months of his life. He’d be subjected to the biggest hate campaign any England player has ever had to face.

As it turned out, it was an experience that helped to define him. In the space of a year, he transformed himself from the most despised figure in the country to a Treble winner.

Circus and the storm

A day before the last-16 tie with Argentina, Beckham had been in the toilet on England’s team coach, jumping up and down with delight. En route to Saint-Etienne, he’d popped into the loo to phone fiancée Victoria, who had some news for him: she was pregnant with their first child. Everything seemed to be falling into place, after a difficult start to the World Cup.

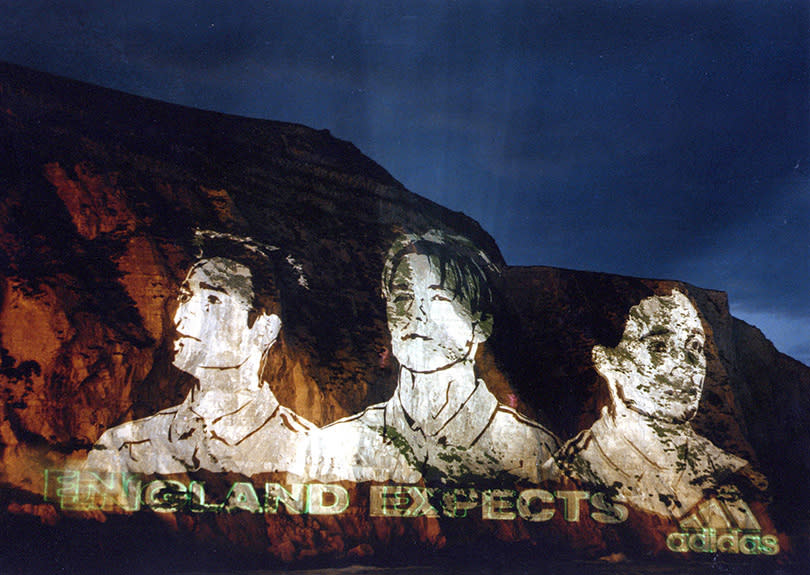

The Manchester United midfielder had gone into the tournament as England’s main man – Adidas projected his face onto the White Cliffs of Dover, accompanied by the words ‘England Expects’. His form for club and country, plus his engagement to a Spice Girl, had turned him into a megastar, and even the man himself was struggling to get his head around it all.

“The other day I was round at Victoria’s house and the postman rang the bell to deliver something,” Beckham told FourFourTwo shortly before that World Cup. “I answered the door and his jaw dropped. He said, ‘Blimey, I never thought I’d see a legend this early in the morning’. That’s just daft – I’m no legend. I can’t believe this is all happening to me.”

Beckham attracted more attention a week before the World Cup, when he holidayed with Victoria at Elton John’s house on the French Riviera and stepped out in a sarong – designed by Jean-Paul Gaultier.

England boss Glenn Hoddle was growing increasingly unimpressed by the media circus surrounding his star man. Beckham was the only player to feature in every qualifying match, but when Hoddle named his team for the opening game of the World Cup against Tunisia, he delivered a bombshell. The midfielder was dropped.

“I don’t think you’re focused,” Hoddle told a bemused Beckham. “How can you think that?” Beckham replied, insistent his celebrity status hadn’t distracted him from his footballing duties.

Beckham had been even more confused when he’d been ordered to attend the pre-match press conference, with the line-up still a secret.

“Everybody could see he wasn’t happy,” recalls Stuart Mathieson, who travelled out to that World Cup as the Manchester United reporter for the Manchester Evening News. “I got to know him pretty well. My first pre-season tour was in 1995 and David was on it – I didn’t know a lot about him then. He was just the pleasant young lad I’d sat next to at breakfast one morning in the team hotel.

“The season after, he was at the Midland Hotel in Manchester to pick up a local award he had won. I went to the toilet and the next minute he was stood next to me asking, ‘What am I supposed to say, Stuart?’ I said: ‘Well, just thank everyone who’s helped you and that kind of thing.' Whenever I see him now, all of the speeches he gives and the company he’s in, thinking back to then, it’s quite remarkable really – he progressed more than I did!

“I thought David handled himself extremely well when we sat down with him for that press conference in France, but I know Alex Ferguson was quite annoyed when he found out that he’d been put in front of the media in that situation.”

A few days later, the Red Devils supremo used a national newspaper column to castigate his England counterpart.

“You can be stronger...”

Beckham was on the substitutes’ bench again against Romania, but started against Colombia – curling in a free-kick to help England avoid early elimination. Back in the team after the press had demanded his recall, he was being lauded as a hero.

But against Argentina in Saint-Etienne, everything changed. Adidas’s pre-match promo, accompanied by imagery of Beckham, proved to be prophetic in a different way than they’d ever intended. “After tonight, England vs Argentina will be remembered for what a player did with his feet,” it said, referencing Diego Maradona’s 1986 Hand of God.

Sadly, they were right. Two minutes into the second period came the barge in the back from Diego Simeone, and the petulant flick with the right foot that earned Beckham a red card and a place in England’s hall of shame. “I can’t control what happens on the pitch – that’s the way I’ve played ever since I was 12,” Beckham had told FourFourTwo before the tournament, discussing the petulant streak that Hoddle and others had warned him about.

This time there was instant regret as he trudged to the dressing room, seeking consolation by phoning Victoria, watching in a New York bar during the Spice Girls’ world tour. He stood by the mouth of the tunnel as England went out of the World Cup on penalties. Had he still been on the field, he would have been one of the Three Lions’ first five takers.

Beckham was largely greeted by awkward silence when his team-mates returned to the dressing room, bar a few brief words of comfort from Manchester United team-mates Gary Neville and Paul Scholes. Then Tony Adams put a hand on his shoulder. “Whatever’s happened here, you’re an excellent young player,” Adams told him. “You can be stronger for this.”

He would need to be. Inside the press room after England’s exit, the atmosphere was toxic.

“You could sense there was a groundswell of ‘Let’s have a go at him’,” remembers Mathieson. “These tournaments are so great to cover and you want an England World Cup final on your journalistic CV. People get carried away. A lot of the English reporters thought the rest of the tournament had been spoiled by him. As the Manchester Evening News correspondent, I was writing something more balanced – I didn’t think it was a sending-off. But I suppose in a different job I might have been similar to the others. You do tend to look for the scapegoat and he was the easy target.

“I remember being in the mixed zone afterwards waiting for him to come through. Gary Neville gave me a few quotes and said he didn’t think David would stop to talk. When David eventually walked through, he didn’t stop and that was understandable. His eyes were red and it was clear that he’d been crying.”

NEXT: Beadle's about

Hate campaign

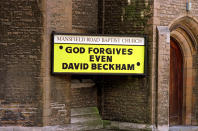

The newspaper headlines didn’t make him feel any better. “Ten heroic lions, one stupid boy,” was how Piers Morgan’s Daily Mirror put it. Two days later, it published a full-page ‘David Beckham dartboard’, with Beckham as the bullseye surrounded by other unpopular figures including Argentina’s leader during the Falklands War, referee Kim Milton Nielsen... and Jeremy Beadle.

Beckham would spend little more than an hour back on English soil upon the squad’s return from France, flying by Concorde to meet Victoria in New York. Even that hour offered him a glimpse of what lay ahead: chased through Heathrow Airport by the media. “How does it feel to let your country down?” one reporter asked him. “Do you realise what you’ve done?” Beckham just kept walking.

The paparazzi were there to greet him when he arrived in America, too. “I thought: ‘This is New York, this shouldn’t be happening’,” he later wrote in autobiography My Side. Until then, Beckham had been able to travel to the US in peace. Not any more.

Due to spend the next 11 days following the Spice Girls around North America on their tour bus, David headed straight to Madison Square Garden where Victoria was preparing for a concert. Within minutes of his arrival he met the Queen of Pop, Madonna. Life was never boring for Becks.

But he was well aware that, back home, the hate campaign wasn’t going away.

At the Pleasant Pheasant pub in south-east London, regulars had acquired a mascot for the tournament – a lifesize dummy dressed in a sarong and an England shirt with ‘Beckham 7’ on the back. At first it was an homage to the Manchester United star, but things took a turn for the worse after his dismissal against Argentina. Pub-goers decided to suspend the £400 mannequin from scaffolding outside the establishment as an ill-advised prank. “The punters are just doing what everybody in Britain feels,” said the landlord.

Swiftly removed by police, the effigy would prove to be the defining image of that summer – the symbol of a campaign that had been stirred up by the media and was now spiralling out of control. The press camped outside the home of Beckham’s parents for days – even setting up a table and chairs on the pavement to sit down for tea and coffee.

When Beckham arrived back at Heathrow in mid-July, half a dozen policemen were waiting at the gate to offer protection.

With Victoria’s tour continuing, his parents had been encouraged by police to stay with him in Greater Manchester, so he wasn’t at home alone. The concerns were justified: Beckham received death threats and bullets delivered through the post. Then a few weeks later, when his parents were back in London, the stranger staring silently outside his home. Beckham called the police, but by the time they arrived, the man had disappeared.

Fergie’s lad

The morning after the Argentina clash, Beckham received a call – it was Alex Ferguson. “Don’t worry, son,” his manager told him. “You’re a Manchester United player. We’ll look after you.”

Many felt that England hadn’t done enough to protect Beckham. Gary Neville criticised the FA for “rubber-dinghy management: they chuck you overboard and look after their own”, while Beckham later claimed that Hoddle “fed the frenzy” by appearing to put the Argentina defeat down to him in post-match interviews.

As the days went on, Hoddle made stronger attempts to defend his player – even suggesting he needed counselling (perhaps from faith healer Eileen Drewery). But in Beckham’s eyes, the damage was done.

At Manchester United, things were different – people were angry at how he’d been treated. “The media were a joke,” complained Neville. Ferguson wasn’t too happy either. “He could hardly have been more vilified if he’d committed murder or high treason,” he later said. The club rallied around Beckham, just as he was starting to fear he’d have to leave the Premier League and seek refuge in Spain or Italy.

“We all supported him,” says defender Henning Berg, a member of that United squad, recalling Beckham’s arrival back for pre-season at The Cliff. “Everybody knew how David was as a person, so it was very easy to help him and be normal around him.

“He was well-liked among the squad before the World Cup, and afterwards too. If he’d been some kind of big-time superstar who didn’t speak to other players it might have been different, but he was never like that. Even though he was famous, he’d always just been one of the boys, working hard and doing the best he could.”

One of their own

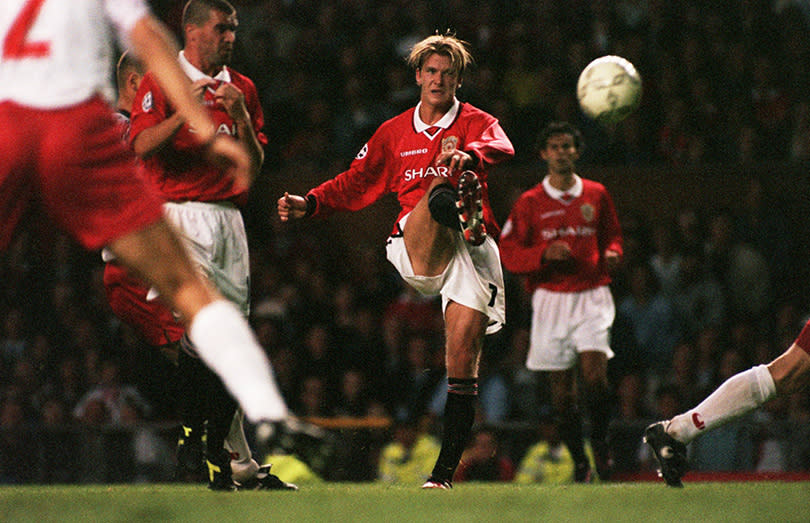

United supporters had chanted Beckham’s name during their first pre-season friendly against Birmingham. Having been afforded extra time off following the World Cup, the midfielder’s first match back in a Red Devils shirts came on tour in Norway against Valerenga, where United-supporting locals gave him a hero’s welcome. On the opening weekend of the 1998/99 Premier League campaign, home fans raised the roof when Beckham fired home a dramatic late equaliser against Leicester at Old Trafford.

“There had always been a huge anti-England thing among United’s supporters,” explains Stuart Mathieson. “They’d always been club rather than country – sometimes they believe they’ve been treated badly by England over the years, and that situation took it to another level. The fans became very anti-England and pro-Beckham – people really got behind him.”

United shielded him from the media spotlight, too. “Fergie was very protective – he wouldn’t let people speak to him,” recalls Mathieson. “Later in the season Beckham started coming out and talking, but it was pretty much radio silence at the start. I can’t remember talking to him about that situation at all. I would ring Fergie every morning and I don’t remember him saying much about it either – he thought that the less said about it, the better.”

United couldn’t shield Beckham from opposition supporters, however. During August’s Charity Shield at Wembley, Arsenal fans had unveiled a banner branding him ‘Beckscum’.

NEXT: “I’ve got this photo at home that still spooks me...”

United’s first away game of the campaign was against West Ham at Upton Park. Just three miles from his Leytonstone birthplace, the back cover of one fanzine carried the message ‘You are not forgiven’, and he had to be escorted off the team coach by an armed guard amid reports he’d be targeted by the Hammers’ notorious Inter City Firm.

“People were waiting for me in the car park – hundreds of them, anger all over their faces,” Beckham later said. The vitriol continued throughout the 0-0 draw, his every touch booed as home fans chanted ‘We hate Beckham’ and ‘You let your country down’. “I’ve got this photo at home that still spooks me,” explained Beckham. “I’m taking a corner and you can see the expression on people’s faces in the crowd. It wasn’t: ‘You’re a crap footballer who cost us the World Cup’. It was way past that – it was: ‘If we could, we’d have you, Beckham’.”

Hammers midfielder Steve Lomas didn’t show him much sympathy either: flooring Beckham with a challenge, then standing over him and screaming at him. “The opposition tried to wind him up,” Berg tells FFT. “When the media makes it out to be a big thing, fans will be influenced by that and opponents will try to psyche him out on the pitch. But he was very level-headed. He let his football do the talking.”

Beckham didn’t respond to the abuse as United drew for the second Saturday running. “He wasn’t a shrinking violet in that game – he was as demanding of the ball as he’d always been,” explains Mathieson. “His reaction was one of great courage. The media had really hyped that game up but I actually remember coming away from it thinking: ‘It isn’t that bad’. I thought: ‘If this is the worst he’s going to get, he’s going to cope with this no problem’.”

The retribution

Beckham did indeed cope, and enjoyed one of the greatest seasons of his career. That despite being in the eye of the storm once again in November, after being involved in an altercation that led to Blackburn midfielder Tim Sherwood’s dismissal. “Beckham still petulant as ever,” was the newspaper headline, somewhat overlooking Sherwood’s role as the aggressor at Old Trafford.

His standout displays were starting to put United in contention for a historic Treble. A trademark free-kick in a 3-3 with Barcelona helped them progress from possibly the hardest group in Champions League history, also featuring Bayern Munich.

Their opponents in the quarter-finals? Inter Milan and Diego Simeone. All eyes were on the pre-match handshake – best described as frosty, as Paul Scholes and Jaap Stam glared at Simeone in solidarity. Two assists and a 2-0 home victory later, retribution was Beckham’s – he even went over to swap shirts with the Argentine.

It would be a happy few days for Becks: within 24 hours, he was in London to see the birth of his first child, Brooklyn. Bookmakers offered odds of 10,000/1 that the baby boy would one day get sent off while playing for England against Argentina.

As the weeks went on, the Treble dream edged closer. Their FA Cup semi-final win against Arsenal was remembered more for Ryan Giggs’s solo effort, but it was Beckham who’d fired United in front with a fine 25-yard strike. At full-time, the midfielder was carried off the Villa Park pitch on the shoulders of jubilant fans. Saint-Etienne was starting to seem a world away.

Trailing Juventus 2-0 in the second leg of their Champions League semi-final, it was Beckham who provided the pinpoint corner for Roy Keane to head home and alter the course of the tie.

On the final day of the Premier League season, with Manchester United needing a win at home against Tottenham to pip Arsenal to the title, it was Beckham who turned the game back in United’s favour, curling in a cracking leveller after Les Ferdinand had silenced Old Trafford.

Stack them up

With the Champions League final four days away, Fergie asked Becks if he wanted a rest for the FA Cup final. “No chance, boss,” Beckham told him. United defeated Newcastle 2-0. “He was a huge influence that season,” recalls Berg. “He wanted to prove that no one was going to stop him from playing football or from being the best he could be.”

Beckham would start in central midfield in the Champions League final against Bayern Munich, moved from the right in the absence of the suspended Keane and Scholes. Ferguson would later describe him as ‘the most effective midfielder on the park’ that night, and two of his expert corner-kicks changed the course of history – Teddy Sheringham flicking on the second of them for Ole Gunnar Solskjaer to poke home the most extraordinary of winners.

While the cameras focused on the Norwegian’s famous knee-slide celebration, Beckham was still by the corner flag, leaping around like a toddler who’d just been introduced to a bouncy castle. At the final whistle, he ran the length of the Camp Nou pitch, his arms outstretched in sheer joy.

Having assisted eight Champions League goals in 1998/99, Beckham was selected as the UEFA Club Footballer of the Year. A few months later, he was officially named the second best player on the planet – runner-up to Rivaldo in the vote for both the FIFA World Player of the Year and Ballon d’Or.

“If Manchester United hadn’t had Beckham in their team that year, they wouldn’t have done anywhere near as well as they did,” reveals Mathieson. “He was the supply line. Coming through what happened against Argentina strengthened his resolve. His character was built in that moment in Saint-Etienne.”

An hour or so after the final whistle in Barcelona, Beckham carried the European Cup out of Camp Nou and into the car park. There, he saw his father, just like he’d done in Saint-Etienne 11 months earlier. He put the trophy down and they hugged, both thinking back to that night against Argentina, and how things had changed.

The red card at the World Cup could have destroyed David Beckham. Instead it spurred him on to greatness. Soon he was England captain and a national hero, thanks to his memorable free-kick against Greece. But it was the 1998/99 season that truly defined him.

“It was the season when I lived a nightmare and dream at the same time,” he later said. “In the end, the dream won.”

This feature originally appeared in the August 2018 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport