DRS is still F1's sticking plaster for a lack of racing

Formula One’s 2022 regulation changes are the most comprehensive since the start of the turbo-hybrid era in 2014 and the most far-reaching aerodynamically for decades.

Their primary aim was to reduce the turbulent air that the previous generation of cars produced, in order to make following easier and the racing better. To achieve this, the 2022 cars generate more of their downforce from “ground effect”, that is to say from the under-floor rather than the upper-body aerodynamic parts “on” the car. This, in turn, was intended to stop drivers having to back off from cars ahead in order to preserve their tyres which obviously had a negative effect on the on-track action.

Reading through the regulations before the season began, there was the potential for the cars to all look fairly similar as the wording and limitations were fairly prescriptive in what was legal. Yet at the first test in Barcelona in February the cars looked quite different throughout the grid, with a variety of interesting sidepod and floor concepts.

However, having the ten cars look different was not the aim of the FIA’s regulations – it was to improve the racing spectacle. There are still question marks over whether they have truly achieved their aim.

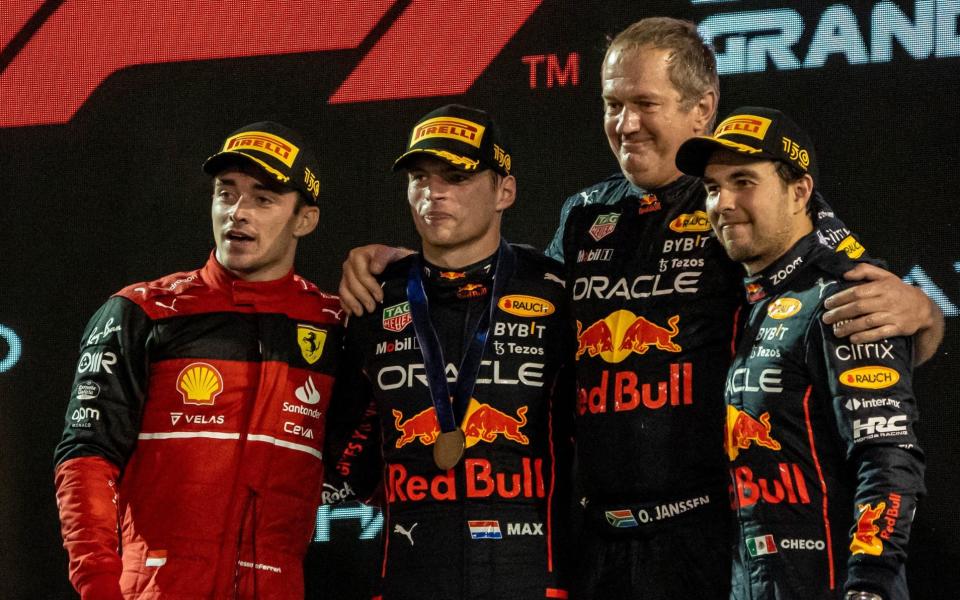

Can the cars follow more closely and for longer than in 2021? Definitively, yes. There have been several occasions where that has been the case, from Charles Leclerc and Max Verstappen’s battle for the lead at the first race in Bahrain to George Russell’s three-lap long duel with Verstappen in Brazil. The tyres, though still critical for performance, do not seem to overheat and degrade as much because of less dirty air created in a car’s wake. Again, a plus point.

DRS still too influential

Whilst the overall effect has been positive, the racing has not exactly been revolutionised. The percentage of progress in improving racing is small. The Drag Reduction System (DRS) is still too influential and powerful when it comes to overtaking. In any set of regulations, having one car reduce its drag, thus increasing its top speed on a straight by 10-15km/h can make an overtake a formality. The continued reliance on DRS ultimately shows that the regulations are still not allowing the cars to go racing.

The final year of the previous regulations saw a lot of convergence in design since the last significant change in 2017, when the cars were made wider, faster and given more grip. 2021 also saw a much closer field: Red Bull and Mercedes were almost perfectly matched, with the midfield teams close to one another and – more importantly – closer to the front than previously. That has unfortunately changed this year. In 2021 there were 10 podiums between McLaren, Alpine, Aston Martin and Williams but this year Red Bull, Ferrari and Mercedes scored 65 from a possible 66 podiums.

As with any big regulation change, a staggering of the order this year was always likely. Yet the potential for the field closing up in the coming years is better than when new regulations were introduced in the past.

We’ve had a season of seeing what is possible and these regulations are more prescriptive than in the past, with less variation available to the teams. That said, leveling the field significantly with the technical regulations alone is difficult.

Drivers’ salaries should be part of budget cap

It is all now about detail. The days of coming up with a novel concept like bargeboards or the double diffuser and finding half a second over your rivals are gone. When you get down to getting the performance out of small detail, the more heads you have thinking about that detail the more you will get out of it. This gives an advantage to the big teams who have more people and better and more advanced facilities. There will always be a leading group out front, but the target should be that they are not in another league to everyone else.

The budget cap, then, has a big role to play in evening things up. It does not do that currently as it does not cover enough. The enormous costs of paying a drivers’ salary should be included in that equation if things are to be improved. A team would then need to make a decision whether to spend their money on a car, or spend it on a driver.

It is probably better to wait until the beginning of next year before fully assessing how successful the regulations have been. The budget cap makes it difficult for teams to do all their desired development in the season. We saw that with Ferrari abandoning upgrades in the final part of the season as they simply ran out of money within their budget cap expenditure. That is something we would never have heard of in the past.

In 2023, there will no doubt be some aspect of “follow the leader” with teams looking towards Red Bull – who came up with by far the best solution for 2022 – for their development path, but it does not always work like that. The variety in designs we have seen so far means there is plenty of scope for development through the years and hopefully flexibility in the competitive order.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport