When football’s laws are so inflexible, referees’ gaffes are harder to swallow

Janny Sikazwe made a mistake and ended up blowing for full time after 85 minutes of Wednesday’s Africa Cup of Nations meeting between Mali and Tunisia. Forgetting to stop the watch during a water break (if that is what happened) is an understandable error – particularly given he was subsequently taken to hospital suffering from heatstroke – and one that could easily have been rectified.

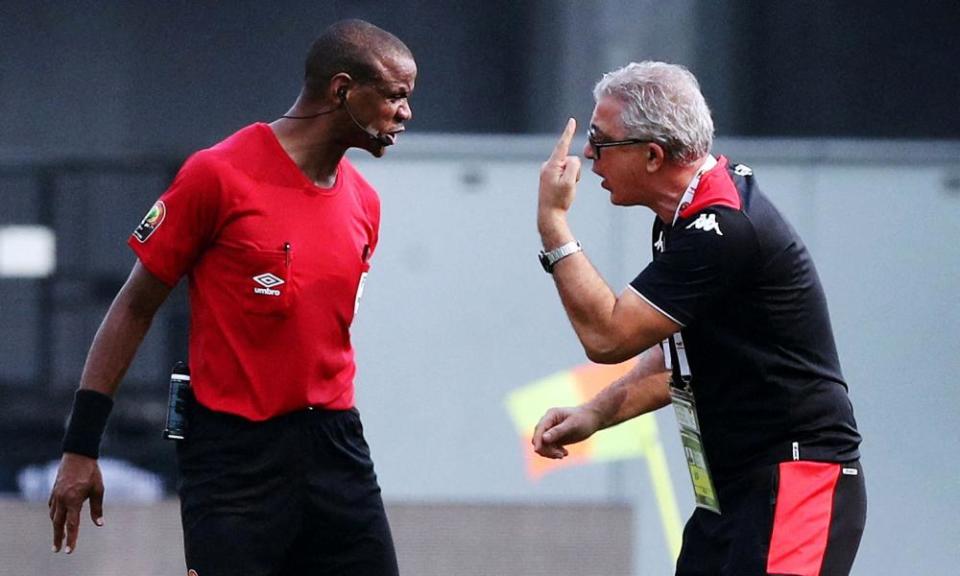

As it was, though, Sikazwe, an experienced referee who took charge of the 2017 Cup of Nations final as well as Belgium v Panama and Japan v Poland at the 2018 World Cup, looked rattled. He sent off Mali’s El Bilal Touré for an innocuous foul, sticking with his original decision even after VAR asked him to review it, and then blew for full time again after 89 minutes and 47 seconds. Tunisia then refused an attempt to restart the game half an hour later, and it remains to be seen what the fallout will be.

Related: Will Coutinho, the costly Barcelona misfit, show his worth at Aston Villa? | Sid Lowe

Much of the discussion has centred on how embarrassing the incident was for the tournament (very, not because European referees haven’t also made mistakes in high-profile games, but because it confirms the negative impression many already have of the Cup of Nations), but it also raises wider issues about refereeing: the issue was less Sikazwe’s mistake than his reaction to it.

Imagine he had seen the surprise of the players at the game being stopped, checked with the fourth official, reset the watch, apologised and moved on with some combination of clarity and humility. It might have taken a minute, but essentially it would have been a quickly forgotten oddity.

Instead he failed properly to reset the time and it is hard to believe his flustered state (which may have been in part the result of his heatstroke) didn’t contribute to the red card. Refereeing is not just about getting decisions right, but also about the projection of authority – which doesn’t necessarily mean being dictatorial; it means persuading the players you’re in control and doing your best.

The thought occurred also during Manchester City’s win at Arsenal, when Stuart Attwell found himself widely condemned for getting a series of decisions right. Ederson’s foul on Martin Ødegaard was apparent only from one camera angle; Attwell can hardly be blamed for not seeing it, and it was equally understandable that VAR should not deem that a clear and obvious error. Gabriel deserved both his yellow cards, while the only way Attwell could have avoided giving a penalty for Granit Xhaka’s shirt pull on Bernardo Silva would have been to penalise Bernardo for simulation, but given he was going down having fallen over Xhaka’s leg that would have been absurd.

But part of the issue was that Attwell simply looks so beleaguered. Attitude matters. Pierluigi Collina or the similarly wild-eyed Gambian official Bakary Gassama he is not. Rather Attwell gives off the air of a hen-pecked husband struggling to make the payments on the over-fancy car he was persuaded to buy. Add images of him looking stressed to television’s insistence his decisions were controversial – a debate largely generated by its own coverage – and the result was furore.

That scrutiny is another major part of the problem, undermining any attitude of control. The way decisions are analysed creates controversy and doubt, particularly when there is rarely any acknowledgement that some decisions are almost impossible to make at speed from a single angle, or that in some cases there probably is no definitive “right” answer.

A player trying to intercept a pass can play onside a forward who was offside when the pass he tries to stop was played

That has created a community of snitches and zealots, constantly peering through the net curtain, determined to find faults to punish. With every nudge on a shoulder, every brush of ball on arm, the question has become not: “Was there an attempt to cheat?” but: “Can we penalise this?” Rather than asking if there was a foul, we ask whether there was contact. Having arms has become a defender’s original sin.

The Premier League is far from perfect but it at least seems to have come up with a workable definition of handball so that the arms have to be carelessly extended from the body for a penalty to be given. Other leagues and the Cup of Nations are working on strict liability: the penalties given against Mali, Tunisia and Zimbabwe in their first fixtures all involved balls being hammered into arms from relatively close range.

Related: Premier League fans may be frustrated but Africa Cup of Nations deserves respect | Jonathan Wilson

Perhaps Zimbabwe’s Kelvin Wilbert’s arm was slightly extended from his body as he hurled himself into the path of the ball but is the game really better if defenders are discouraged from attempting blocks like that? If matches are going to be decided on such moments of randomness, then for all the football merit involved we may as well hide gold rings randomly round the pitch and award a goal for every one found.

Similarly, an over-literal interpretation of the offside law now means a player trying to intercept a pass can play onside a forward who was offside when the pass he is trying to stop was played. It happened for Joe Ironside’s goal for Cambridge against Newcastle and it happened for Kylian Mbappé for France against Spain in the Nations League final. Clearly that is absurd: what sense does it make that a goal stands if the pass brushes the defender’s foot but not if he misses it entirely? That’s not how the law was ever meant to be applied.

As with handball at the Cup of Nations, there has been an inversion, as though the laws, rather than shaping and controlling a game that predates them, have become a sacred text from which the game derives. Since David Elleray became technical director for the law-making International Football Association Board, a puritanical fundamentalism has taken hold.

And that is not just bad for the shape and rhythm and basic fairness of the game; it’s bad for referees, undermining and dehumanising them. When the law is so cold and so inflexible, it makes errors such as Sikazwe’s far harder to tolerate, makes it far harder for referees to build the consent that lends them authority.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport