'I was the king of sabotage': Ronnie O'Sullivan on controversy, comebacks and becoming a carer

Ronnie O’Sullivan is driving over from Essex and says he’s bringing a friend. “Gloria’s with me. She’s brilliant. She picks me up when I’m properly on the floor.” It’s only two days since he won the World Snooker Championship – his sixth triumph in the sport’s biggest contest. Why would he be on the floor?

“You must be happy,” I say, when he arrives at my house – he pocketed £500,000 along with the trophy. He laughs. “You know what? I got up this morning and I felt a bit low. And I remembered every time I win a big tournament it puts me on a low. But I’ve accepted it. It’s just part of any high.” Typical Ronnie.

O’Sullivan and I go back 19 years. We met just after he had won his first world title, hit it off, and I helped him write two books. No sportsman has ever worn his angst on his sleeve quite like him. To be fair, there has been plenty to have angst about – in 1992, the year he turned professional, aged 16, his father, Ronnie Senior, was jailed for murder. Four years later, his mother, Maria, was jailed for tax evasion, leaving O’Sullivan to look after his younger sister, Danielle. Then came drugs, breakdown and despair. If this sounds bleak, O’Sullivan is also one of the warmest, funniest, most generous people I know.

Today, he is wearing shorts and an old T-shirt full of holes, sprigs of chest hair poking through. Gloria is tiny, smartly dressed and 72 to his 44. They have been close friends for 30 years. She is recovering from a triple heart bypass and oesophageal cancer.

O’Sullivan has changed very little over the years. He could still pass for a Gallagher brother, but occasionally, when he’s knackered, he looks like Aloysius Parker from Thunderbirds. In winning the World Snooker Championship in Sheffield, he secured a record-breaking 37th major snooker title. He was always regarded as the sport’s most naturally gifted player; now the consensus is that he’s the greatest.

Ronnie is called the Rocket for his speed and power. But there is also a sublime grace to his playing – the way he makes the cue ball dance, the delicacy with which he picks off balls and opens up the pack, his balance, the ability to swap from right to left hand depending on his shot or mood. In a sport not overly blessed with charismatic players, he has been the personality of snooker for a quarter of a century.

Then there are the verbals. Every time he opened his mouth in Sheffield he made headlines. Asked why older players like him were still winning, he said it was because of the poor standard of the youngsters. “Most of them would do well as half-decent amateurs, not even amateurs. They are so bad ... I would have to lose an arm and a leg to fall out of the top 50.” Sponsors winced and the pundits apologised, saying Ronnie will always be Ronnie.

He was only stating the bleeding obvious, he says today – it’s bonkers that he should win the world title at 44. “I’m getting worse and I’m still winning as a part-timer. It’s an old man’s game now.” He grins. “As I get to 60 I’m going to be in my prime! When I was 28 I thought: ‘I’m going to retire at 30.’ The shelf life used to be about 15 years, now it’s about 50. I’m not sure it’s a good thing though. It’s more depression and anxiety for me.” He has always had a love-hate relationship with snooker. He only plays when he fancies these days, and his critics say he disrespects the sport. But they have always said that.

O’Sullivan is gasping for a cuppa and insists on making it himself. “I said to my mate: ‘How do you get your tea so good?’ He says it’s all about pouring the milk slowly.” He pours it painfully slowly, ever the perfectionist. He is still thinking about the game’s slipping standards. “A lot of the players came up to me and said, ‘You’re 100% right’.”

That wasn’t his only controversial statement. He said he preferred playing at Sheffield’s Crucible theatre with no audience. Again, he says, this makes perfect sense. “My biggest fear is embarrassing myself, and with no crowd there’s no one to embarrass myself in front of. But when somebody’s paid for a ticket and I’m stinking the gaff out, that’s my worst nightmare.” There was a socially distanced audience for the final. “When they put a crowd in for the final I struggled with it. I thought that if I play bad, how much of a letdown that would be.” He doesn’t mention that he reeled off eight frames on the trot to secure victory.

At his age, he says, he knows he can only win by guile. O’Sullivan studies other sporting greats for inspiration, and explores the mental side of the sport with the psychiatrist Steve Peters. “I said to Steve: ‘I’m not going to win this through talent.’ I watched Tiger Woods win Augusta and he ain’t gonna blast them away winning by 15 shots any more. It’s not about ability, but about who’s got the balls to get it over the line. I said we’ve got to find a way where my mental skills are good enough to sweat it out, be patient and not sabotage. Because I was the king of sabotage.”

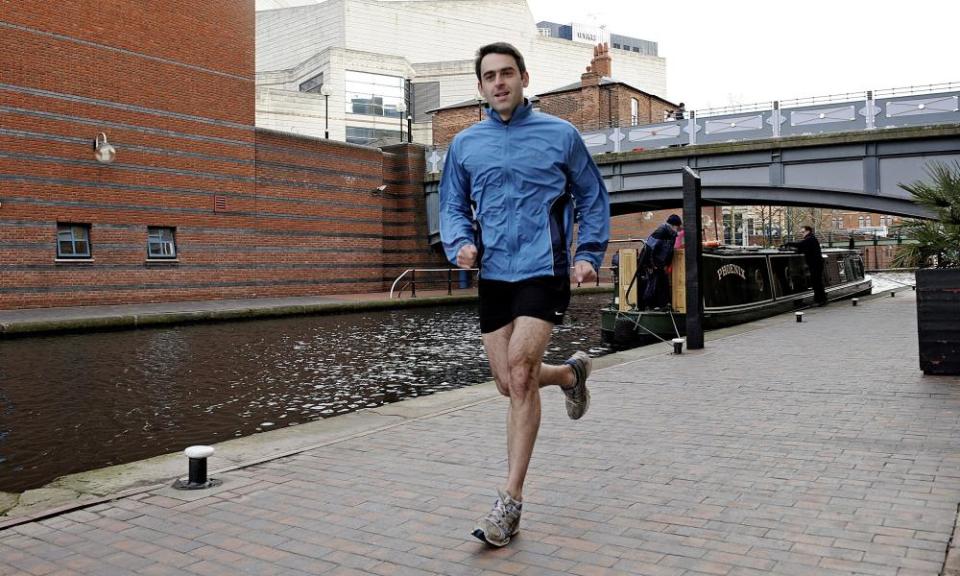

Often, he simply didn’t want to be there. In his 30s he became obsessed with middle-distance running. “A lot of the time I would think: ‘I don’t actually want to win this match because I’ve got a five-mile cross-country race I want to win back in Essex.’ Running became more important than snooker. I’d much rather be running in Woodford in October in mud than be in the final of the Northern Irish open in Belfast.” He grins. “Although I love Belfast and playing there.”

Gloria listens as he talks. O’Sullivan says that as well as being one of his most loyal friends, she is also one of his fiercest critics. I ask her where he most often goes wrong. “The friends he chooses,” she says.

When I first met him he was verging on the socially phobic, often terrified of talking to people. In his mid-20s, he ended up in the Priory, suicidal, and was treated for drug addiction. Since then he has, by and large, remained clean. How has he changed? “I’m less scared of people now. And I’ve learned not to be so trusting. I’m no longer interested in fair-weather friends.” Were there many? “Yeah. I was always a bit of a people-pleaser, so I’d go out of my way to overcompensate, and it was draining.”

He says his partner, the actor Laila Rouass, has helped toughen him up – as well as Gloria, of course. “Laila’s just a bit more streetwise than me, a bit more savvy.” A few years ago, he got conned out of £125,000 in a business deal and it floored him. “I was gutted ... devastated. It took about three years to get over it – not the money, the trust. I became distrusting of everything and everybody.”

That’s always been his problem, Gloria says, surrounding himself with bad ’uns. “I’m the first one to slag him off if he’s wrong, ’cos that’s what friends are about.” What does she slag him off for most often? “For being stupid, for being too soft-hearted. I tell him to pull himself together and grow a pair of balls.”

O’Sullivan says that is true. “When I surround myself with shit people, she’ll be like, ‘Get the fuck out of here’, to them. I never know it’s going on. She won’t let anyone take a liberty with me. I’m a bit soft and she’s not.”

A year after he was conned he had another breakdown – again at Sheffield, in 2016. “I was in hospital in London in between my first and second round at the World Championship. I was doing too much work, living out of a suitcase, booked too much in. I couldn’t move.”

Now, he is in a good place. He came off medication when he realised it was making him moody and he was taking it out on his son Ronnie. (O’Sullivan has three children.) “I had a go at little Ronnie once ’cos I was on these pills, and it wasn’t his fault. I thought: ‘I’m not letting medication turn me into an irritable old man.’”

He is sticking with natural serotonin – running. In lockdown he got himself a coach and has not looked back. “I can run for an hour, 7.45- to 8-minute miling. Running is my drug.” He is convinced running makes people happy. “I’ve never seen [Joshua] Cheptegei look unhappy. How can you look unhappy after a 26-mile run? Running just gives you a natural high.”

I ask him for his highlight at this year’s World Championship. His nose twitches with delight. “Running. When I was up there I’d wake up and think: ‘Fuck, I’ve got to do this today’, then at 7.45am I’m running through the peaks and I’ve forgotten about my snooker. I’ve had breakfast, had a shower, had a great run, and I think: ‘Oh, I’ve got to go and play a few games of snooker’, so if the snooker goes shit I’ve already had a good day.

“Running for me is the perfect thing ’cos they are just nice people. It’s not like cycling, where you’ve got to spend £10,000 on a bike. You get a lot of arseholes in that sport because they’ve got money and they think money is the all-important thing. I can’t stand people like that. You don’t get them type of people in the running world.”

I ask him about the future, expecting him to talk about books, endorsements, punditry and a bit of snooker. “The one thing I thought I’d excel in was being in the care industry,” he says. Is he serious? He nods. “I can empathise with people in addiction. It could be addiction, mental health, autism, anything. You’re in the CQC game, so it’s about providing a safe environment and getting people on their feet.

“I was in rehab in 2000 and it was the biggest life-changer for me. It was tough, but what I needed. Without the 12 steps, without taking myself out of society, without going to a treatment centre, maybe I wouldn’t have got to where I am today.” Maybe you wouldn’t be here full stop, I say. He nods. “Yeah, totally.”

He empathises with people who are vulnerable, he says. Would he be an active carer? “Yeah. I’m not going to say I’m going to change people’s nappies, but I want to provide a safe environment for them and make their life as happy as you can ... We’re starting off small. One place, six or seven beds. It will probably be a place for people with mild disabilities who don’t need 24-hour care.” He expects to settle on the premises in the next few months. “When I finish playing snooker I want to train as a counsellor. I want to understand the business and the mental health side.”

What’s behind all this? “I’ve had enough of arseholes. And when I look at these people who need a care home, they just want a roof over their head, three meals a day, you give them a job to do, you take care of them. I’ve had enough of the dog-eat-dog thing. I just want to be in a business where you’re taking care of people.”

“I think he’ll be good at it ’cos that’s where his heart is,” says Gloria. “You were so good to me when I was ill. I think it frightened you a bit.” Lest I think she’s soft, she loses the sentimentality. “He’d earn money from the homes. We all want money, we’ve all got to live.”

O’Sullivan bursts out laughing. “Nobody loves a pound note as much as Gloria!” Anyway, he says, he can run care homes and still play snooker. And maybe there will even be time for a bit of reality TV. He’s considering I’m a Celebrity now that the Australian outback has been replaced by a castle in Wales. “It’s not like Big Brother where you’re destroyed. The worst that happens is they eat a few bugs and come out saying: ‘I had a great time in there.’”

If O’Sullivan ran care homes what a contrast it would be with his mad/bad boy image. So much of that is a media construct, he says. “If I’d been a bit savvy I’d have had a good agent. With people like [David] Beckham, you see what they want you to see of them ... I think people now see me and think: ‘He’s not actually a bad fella, you know, he’s not as crazy as everybody thinks.’”

He turns this over in his head. Some people do still think he’s a bit off the wall, he adds – and he’s happy with that. “We all fit into some sort of box. And I appeal to the crazy gang, the nutcases.” He shouts out suddenly, like an excitable fan. “Yeaaaaaaaah! Go on Ronnie!”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport