The Last Post has sounded for cricket on Channel Nine – but the great game carries on

It’s all about the trumpets. They cut through everything, long shoots of clean brass. Bwaah-bwa-bwaaaaaah. Bwa-bwa-bwa-bwaaaaah. But the instruments in the background were there first – violins or cellos (who among the unqualified knows?) with bows grinding staccato in that fibrous violence that turns strings to drums. Holding down a steady background beat, dum-dum-dum-dum-dum-dum-dum, cavalry charging a fortification.

It’s drama, the sense of imminence. A heartbeat could only hit this tempo soaked in adrenaline. Then the horns return, like on days of heavy cloud when a few fat beams of sun stab earthward in homage either to God or The Lion King. This time, the tripartite phrase ends further up the octave, a searching high note, the questioning inflection jammed incongruously at the end of so many Australian statements. Then the main strands dissolve to final fanfare: diddle-um diddle-um diddle-um, bomp bomp bomp bomp. An ornate flourish like a mirror frame in a grandparental bedroom.

Admittedly, describing music is rarely effective at making the reader hear it. Transliterating it in plain text is almost as useless and far more silly, while also denying the pleasure of the description. But apply mine to the start of a day of televised cricket, and some of you may find that your internal audio library sends the theme springing to life.

Wide World of Sports. The theme that launched a thousand broadcasts, the ritual prelude on Channel Nine. When I was growing up they tried to display 1990s modernity by switching up to electric guitar. More recently came a return to the classic mode, an evocation of times past in a search for the reflected credibility of heritage. At the first Sydney Test after Richie Benaud’s death, the devotees who bear his likeness used their trumpeters to send the tune echoing around the empty, rain-soaked stands in an accidental lament, naked horns finding the feel of a sporting Last Post.

I was always an ABC kid if given the preference: radio up, TV down, my voice of summer more Jim Maxwell than Benaud. But still, Nine’s omnipresence soaked in. To this day, I have a vital Pavlovian response when the lift doors close at the Sydney Cricket Ground and those notes fire up on the internal speakers. A snap of anticipation; feel the horses’ hooves approaching the brow of the hill? And no single refrain conjures cricket more potently than when Bill Lawry chimes in over the music: “Bowled him! The last ball, can you believe that?”

But no more. The SCG Trust will have to fall back to The Girl From Ipanema, because Nine’s days hosting the home season are done. For 39 summers, such was the right of the station that was once Kerry Packer’s, but for the next six years at least, it has gone. At the rate media consumption changes in this era, television in its current iteration may be close to extinct next time around.

Given my frank assessment three years ago of Nine’s shortcomings, readers might expect to see me holding a cocktail soiree on the broadcast’s freshly furrowed place of interment. But a late-life dip doesn’t invalidate all that came before. The most venerable citizen can lose dignity in dotage.

Nine changed the game from 1979 on, growing the number of cameras as standard, updating the surrounding technology year on year. Graphic overlays, multi-angle replays, animation, file footage, speed guns, super slow-mo, pitch maps. Viewer aids like Hot Spot and Snickometer became incorporated into the official Decision Review System. If Nine wasn’t first to innovate, it acquired and backed others’ inventions. The quality of the technical crew was evident: whatever one thought of the accompanying commentary, the camera operators almost never lost a ball.

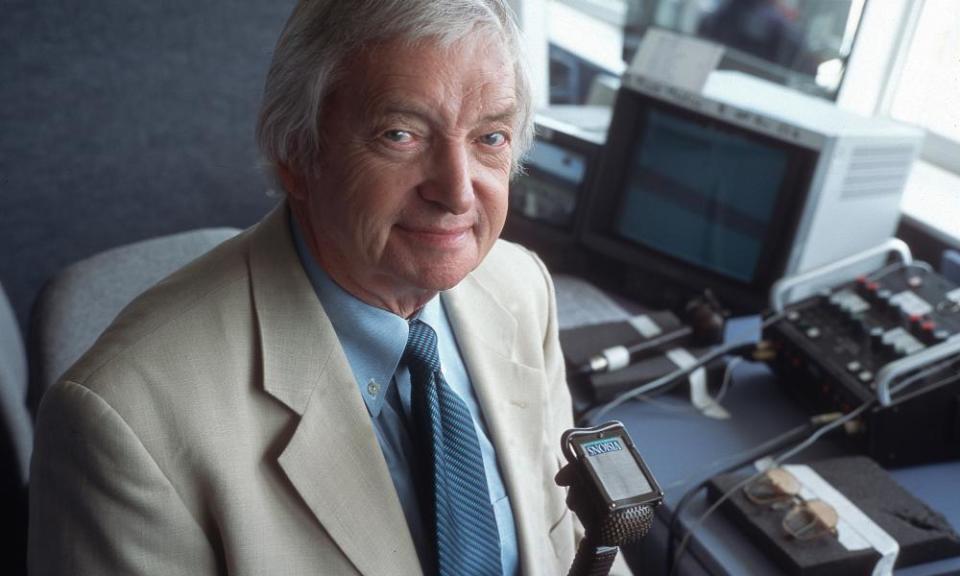

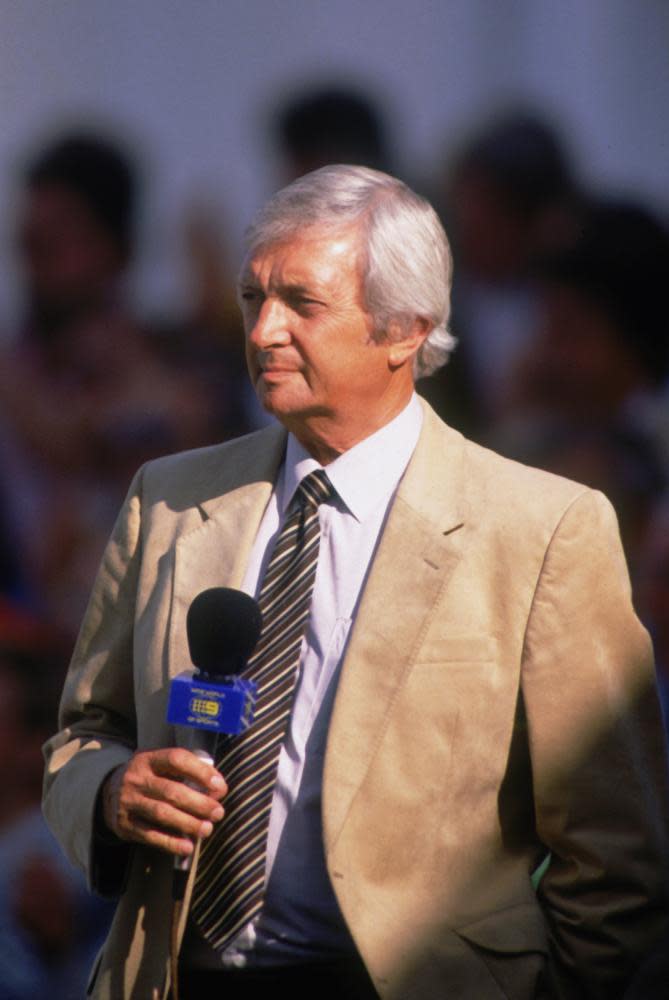

That made a strong foundation for the public facade. Nine on your screen was summer undeniable. Tan slacks, straw hats, cream jackets. The Beige Rainbow, in all its muted splendour. Richie, Bill, Tony, Ian: way less cool than the Beatles, but stars in their own milieu way. Others who came and went around them: Max Walker, Doug Walters, Keith Stackpole, dozens more. Collectively the genesis of the Twelfth Man, the parody which won Nine’s callers more popularity and affection than they could have achieved on their own, the broadcast feeding off Billy Birmingham as he fed off it.

This affection has ended up as a nostalgia trip, an indulgence in past kitsch: Greig with his Weatherwall, or the Toyota keys jammed into the pitch in such a way that would now have umpires and groundsmen in conniptions; terry towelling hats and pastel t-shirts with piped sleeves; the cigarette ads and unalloyed skin cancer and the strict limit of 24 cans of full-strength beer per person per day, give or take the odd vodka watermelon.

But it’s also to do with genuine attributes. Lawry feigning querulous indignation, or not feigning it, while Greig thudded along with bass-drum bluster. Chappell always ready to fire a blunderbuss, rather than the popgun criticism of later colleagues. Benaud seen as a venerable old sage, Cricket Yoda saying “Bowl the flipper, he will,” while people forgot the feisty operator who backed Packer’s rebellion at great risk to his own career, or who barbecued Greg Chappell live on air after the underarm ball.

Of course, that cast faded away: Benaud and Greig into the dissolution of death, Lawry into retirement bar the odd Melbourne game, the youngest in Chappell now an elder statesman among less robust company. Over the last decade, they were gradually replaced by recent players with no training and inadequate direction. The quality tanked, in a way that I covered in such detail as to spare anyone a repetition.

The interesting thing is, Nine did improve in its last two summers. When new head of sport Tom Malone came in, old director of cricket Brad McNamara was soon on the way out. Some commentary dead wood was cut, in James Brayshaw and Brett Lee. The call dropped back to two-man teams, helping with focus. Guest commentators from visiting nations returned. It wasn’t perfect, but there was more cricket and less barf. Some people involved had recognised the problem.

But even with good intentions, it felt like Nine was done. Richie, Bill, Tony, Ian: those names speak too of demographics. Solid white blokes of Middle Australia, notwithstanding a South African twang or a French connection. White men’s voices in what for so long was a white man’s sport, with a bare few players of colour in Australia’s long Test history, and a women’s team pushed to the margins. Cricket is trying to catch up on this homogeneity; the homogeneity eventually caught up with Nine.

The backlash to its most recent season promo was instructive: a line-up photo of Lawry, Chappell, Mark Nicholas, Mark Taylor, Ian Healy, Michael Slater, Michael Clarke and Shane Warne. A parade of pink faces in dark suits, the monotony couldn’t have been more starkly illustrated. Online responses took the piss mercilessly. Other publications ran it as a story, or wrote critical op-eds. But then this was absurd given their own positions: Australian broadcasters and written outlets between them hired a total of four women to cover the Ashes.

Perhaps what really did the damage was Nine’s language. “Meet our Ashes commentary team,” it said, when anyone who had vaguely glanced at cricket in the last 15 years would have seen the same names, same faces, same gags: a parade of former Australian captains spiced up with a couple of former England captains. It seemed to be celebrating the lack of change.

Meet our #Ashes commentary team. pic.twitter.com/5OP6KLsqjy

— Wide World of Sports (@wwos) November 17, 2017

Sometimes, perception is all that matters. It wouldn’t have mattered how prime minister John Howard campaigned in 2007: people were tired of him, so they moved him on. Lose your public, and accumulated faults that have been let pass are charged to your account en masse. Recent assuagement won’t spare your past mistakes.

There are lessons in this for Channel Seven and Foxtel as they set up to replace Nine. Not everyone commentating on a Test match has to be a middle-aged man. Not everyone has to be a former cricketer. Not everyone has to be Australian. At a base level for the broadcaster, it’s not even about equality, it’s about boredom. Inclusion isn’t a buzzword, it’s a way to bring people in. That, above all, is what a television network is trying to do.

But whatever Nine’s failings, some part will remain. For those who grew up on it, or were steeped in its brew over the course of years, it has seeped into our bones. The background rumble of distant spectators, of wooden bench seats creaking under the hot sun. The silence, the scrape of spikes. Some things will continue and some will be gone. Cricket will carry on, a summer cicada squeezed out soft and fresh to leave a former carapace. Those remnants will be left, just a current running through us that will twitch to life when we hear a trumpet line, or a familiar voice. “Bowled him! The last ball, can you believe that?” The last ball has been bowled. We believe it.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport