‘Like a lockdown’: in 2022, Australians are still feeling the fear and anxiety of Covid

Most of the population is vaccinated and harsh restrictions have ended. But for the 40 people Guardian Australia spoke to, it doesn’t feel like it’s over

Ashleigh Cooper has spent the new year indoors. Around her, in the suburbs of Melbourne, Covid cases are soaring.

It’s a story repeated in every Australian state, except Western Australia.

Australia recorded more cases in the first two weeks of 2022 than in the previous two years combined. For most, the threat posed by Covid has eased – 92.4% of Australians over the age of 16 are fully vaccinated, and 18% have also had a booster shot. And the Omicron variant, which has ripped through the country since December, appears to result in a less severe illness, in most cases, than previous variants of Covid-19.

Public health orders enforced by strict and punitive laws have been replaced by a mantra of personal responsibility. It is up to individuals to determine and manage their own risk. For the most vulnerable people, the only way to manage this risk is to retreat.

Related: NSW expects Covid hospitalisations to peak next week. These key charts will show if that’s happening

Cooper is disabled and immunocompromised. She went into self-isolation two weeks ago.

“For me the risk is too high,” she says. “It is very strange to watch the rest of the world say ‘we will go out and it will be fine and we will get sick and it will be fine’. I would not be fine – I had my booster shot last week and was severely unwell for five days. I do not want to get Covid.”

Guardian Australia spoke to more than 40 people about how they were feeling at the start of the third year of the pandemic. Many like Cooper have gone into self-isolation to protect themselves or a vulnerable loved one. Many others say they have chosen to go back into something resembling lockdown until their children can be vaccinated or until the outbreak peaks.

Cooper says she felt significantly safer when Melbourne was in lockdown and finds the argument that people should “get over” their concern about a global pandemic “incredibly invalidating”.

“We should absolutely acknowledge that [lockdown] was bad and a lot of people suffered, but a lot of people are also alive now because of it,” she says. “I know that I was safer.”

Also invalidating is the implication, from some public health messaging and public responses to death announcements, that a disease is less devastating if most of its victims are people who have pre-existing conditions.

“Almost everyone has a pre-existing condition,” Cooper says. “What’s the price that we are willing to pay in order for people to be able to go and have brunch?

“Are you willing to justify risking the health of vulnerable people for that privilege?”

‘Utter confusion about what we should be doing’

Most people who spoke to Guardian Australia are still recovering from the impact of long lockdowns and do not want a return to restrictions. They just want an indication from governments both state and federal that they will be supported and able to easily access tests and healthcare as the outbreak, and any new variants to come, rolls on.

Martin Radzaj says he has found the start of 2022 to be the most difficult time in the pandemic because of the “utter confusion about what we should be doing”. He also feels the loss of the sense of collective action which, for some, underscored the long lockdowns of 2020 and 2021.

“The thought of lockdown again is what is giving me a lot of anxiety and a lot of dread … it scares me,” says Melbourne man James Burke. Two years of mostly home schooling has given his youngest child, who started kindergarten in 2020, social anxiety, and his older child had a panic attack at the prospect of returning to face-to-face learning.

“We paid the price [of lockdown], we bought the government time to build capacity in our health services. And they lost control in just two weeks.”

The anxiety of past outbreaks has been replaced with anger at state and federal governments, and a growing sense of despair that the pandemic will not end, at least not any time soon.

Hannah*, a vision-impaired support worker in Melbourne, says the 2021 lockdowns left her feeling “emptied out”.

“I felt like half a person,” she says.

Like many who spoke to Guardian Australia, she focused on the vaccine rollout – when everyone who was eligible was double-vaccinated it would be OK. Then Omicron happened, the inevitable consequence of a lack of global vaccine equity, and the promise of a return to normal life has been pushed back once more.

“It now feels as though it is going to define parts of my life trajectory where I was hoping it wouldn’t,” she says. “Two years [living in a pandemic] is very different to five years when you only get three good months every year.”

Northcote woman Phoebe* is also feeling a sense of arrested development. The public servant, 25, contracted Covid along with 16 others at a house party late last month. She still can’t smell or taste anything and several of her friends remain unwell.

“Some people are going to get chronic illness from that, and we are in our 20s,” she says. “Every single one of us was double-vaccinated as soon as we were eligible but we are not eligible yet for a booster. It just feels like there’s no plan and younger people are bearing the brunt of it.”

Related: NSW Covid update: health officials increasingly confident cases will plateau next week

Phoebe says her social circle has split in two: those who have had Covid and are now feeling invulnerable for 30 days – despite warnings that earlier reinfection is possible – and those who are curbing social activities to try to avoid it.

‘Have we given up?’

Thomas Barbera says his friend groups have done the same, and it has caused some uncomfortable conversations. “People do not want to feel that you are judging them or saying that what they are doing is unsafe – and it is not inherently unsafe, they just have different risk tolerance and different priorities than you,” he says.

Barbera says he is still struggling to come to terms with a health policy that expects and accepts that hundreds of thousands of Australians will get Covid, after two years where a handful of cases would send the city into lockdown.

“Two years of having ‘get a test’ drummed into you and then suddenly people are told not to get a test unless they fit certain criteria … I found that really hard,” he says. “It felt like, have we given up?”

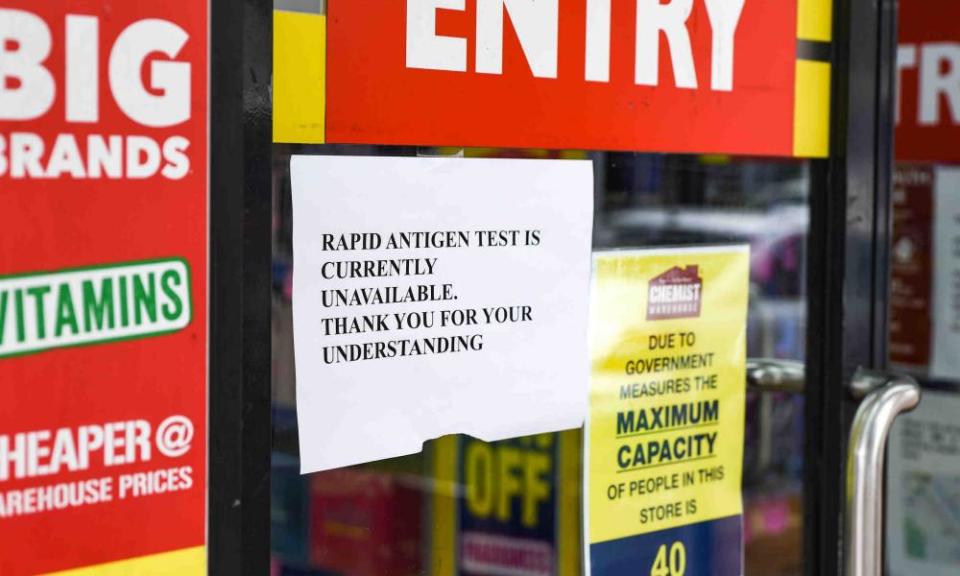

His store of rapid antigen tests, bought in early December, has been slowly dwindling as he hands them out to friends who have been identified as close contacts.

Almost everyone who spoke to Guardian Australia said they would feel more comfortable moving around if they had access to free, readily available rapid antigen tests.

Australian government frontbencher Simon Birmingham told the ABC on Friday that demand for testing, from both PCR and rapid tests, had been “far in excess of what has been modelled in Australia and all around the world”. The Australian government has since ordered $62m worth of rapid antigen tests.

Kylie*, a midwife working in Melbourne hospitals, says despite difficulties with testing and high case numbers there is cause to be optimistic.

“There are more women with the virus who are having babies, but unlike 2021 they are not gasping for breath,” she says. “In the past fortnight none of my patients have gone to ICU. So for me, right now, I am seeing the light.”

Milly*, a young woman from Melbourne, says that two years of going in and out of lockdown has caused a downshift in her lifestyle that feels akin to being retired.

“I have adjusted to living a more sheltered life and enjoy being in my house, running the same route, cycling the same loop, doing the Wordle, going to bed on time,” she says. “‘[The] big difference is I have no energy for or interest in working, just want to read books and chill. Took a while for the anxiety to die down to get to this point but now I don’t want to do anything else.”

Richard Chigwin is experiencing his third summer without customers. He owns a series of ecotourism huts in the New South Wales Blue Mountains and lost the 2020 summer holidays to bushfires and 2021 to coronavirus. 2022 was supposed to be different, but “It feels exactly like there is a lockdown. You are not even fielding inquiries – it’s school holidays in January, that’s not right.”

As a sole trader, Chigwin wasn’t eligible for government support in earlier rounds. Other business owners say they are finding this summer more difficult than previous seasons because there was no financial aid available.

A Victorian-based consultant told Guardian Australia they were still receiving commercial rent relief until this week. Now that has ended too. “Like everyone else, we just have to muddle through on our own.”

Lydia Napoli also works in hospitality in NSW.

“It’s a nightmare,” she says. “My husband is working overtime, heaps of chefs and [front-of-house staff are] unwell or close contacts, and there is no support. I’m double vaxxed and feeling like, what was the point? There’s still high chances of new variants. It’s all just exhausting.”

Karen McVean, a Melbourne-based remedial massage therapist, has chosen a different approach. “As the Covid years continue we are losing our magical thinking it will go away and not be a changing burden to our life,” she says. “Personally, I feel better with accepting that Covid is an ongoing issue. How can I best get on with living my best life?”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport