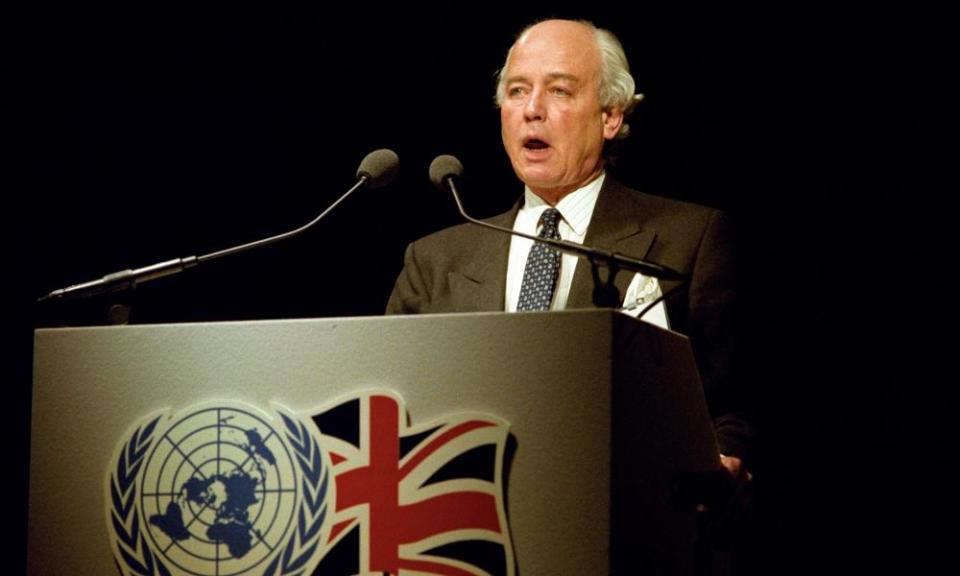

Lord Waddington obituary

Being home secretary is never an easy job, but David Waddington’s brief tenure in that great office of state at the tail-end of Margaret Thatcher’s time as prime minister was more tempestuous than most. Plucked from being chief whip at the age of 60, Waddington, who has died aged 87, had to deal with a string of serious problems. There was a prison siege, poll tax riots, miscarriages of justice for the Birmingham Six, a contentious war crimes bill, and broadcasting legislation that established satellite television. He lasted only 13 months, from 1989 to 1990.

Waddington, a barrister and crown court recorder on his local north-western circuit in Lancashire, was a Tory loyalist, unostentatious to the point of greyness: diligent, competent but uninspiring and uncharismatic, whose entire ministerial career was served under Thatcher. At junior ministerial levels he took on some of the least rewarding jobs in government, including trade union reform and immigration and asylum issues, and was able to mollify and reassure Tory backbenchers that he was on their side with his robust rightwing views, in favour of hanging and corporal punishment.

He had a shrewd appreciation of his talents, once telling parliament’s weekly House magazine: “I would like to be remembered as a decent local buffer who wasn’t all that clever, but in his own way tried to do his best.” His wife Gilly (nee Green), whom he married in 1958, was said to be the driving force in the relationship.

Born in Burnley, Lancashire, David was the fifth child and only son of Charles Waddington, a solicitor, and his wife, Minnie (nee Pickles). The family also owned a cotton mill. David was sent to Sedbergh, a spartan public school in Cumbria, where it was said that his interest in politics was first stirred when he was placed in charge of collating the school’s Keesing’s Contemporary Archives (a printed summary of world news) in preference to cross-country runs. He went on to read law at Hertford College, Oxford, where he became president of the university Conservative Association (1950). Called to the bar in 1951, he then undertook two years’ national service and returned to Lancashire to practise as a barrister. He became a QC in 1971.

A friend remarked later that as a lawyer he was “no great intellectual, but very good at making a point and stabbing at it”, a doggedness shown later in his ministerial career. Among those he defended was Stefan Kiszko, wrongfully convicted of murder in 1976, a case in which police concealed evidence of the defendant’s innocence.

It took several goes for Waddington to become an MP. He first contested Farnworth in 1955, then Nelson and Colne in 1964 and Heywood and Royton in 1966 – all safe Labour constituencies. His chance finally came with the death of Sydney Silverman, the long-standing anti-hanging campaigner and veteran MP for Nelson and Colne, in 1968. Waddington, riding a tide of public discontent with Harold Wilson’s government, won the constituency in the subsequent byelection, in which his Labour opponent was Betty Boothroyd, the future Commons Speaker.

He held on to the seat at the 1970 general election and in February 1974, but lost it in that October’s general election. He got back into parliament via a byelection nearly five years later in March 1979, two months before Thatcher’s general election victory, in the safer seat of Clitheroe, subsequently renamed Ribble Valley, which he held until 1990.

Waddington soon found himself promoted, first to the whips’ office, then as junior minister at the Department of Employment (1981-83), where his lawyerly training helped him pilot through the government’s restrictive trade union legislation under Norman Tebbit. Waddington did not like trade union leaders: “very nasty people in positions of authority,” he said.

Following the party’s landslide victory in 1983, he was moved to the Home Office as minister of state in charge of the government’s immigration policy. This was summarised by opponents at the time as largely trying to keep black people out, and the minister was doggedly diligent in perusing all refugees’ claims. He declared that Sri Lankan Tamil asylum seekers fleeing the country’s civil war were “mainly bogus”, but found no difficulty in granting immediate citizenship to the white South African teenager Zola Budd so that she could run for Britain in the Olympics, particularly as she had the strong backing of the Daily Mail.

This outlook landed him in some difficulty when one Sri Lankan asylum seeker, Viraj Mendis, sought sanctuary from deportation in a church in Manchester for two years, supported by the congregation. When local students protested about the Mendis case, Waddington suggested their parents should flog them.

Following Thatcher’s third general election victory in 1987, he became chief whip, in which post he discreetly warned the increasingly hubristic prime minister that there was growing unrest on the backbenches over the poll tax. She took no notice, and in 1990, after she had appointed him to be home secretary, he had to deal with the poll tax riots. During his tenure he was also confronted by a three-week rooftop protest by prisoners at Strangeways jail in Manchester and mounting street disturbances in various parts of the country. It was a period, too, when public pressure was mounting to reverse the convictions of the Guildford Four, Maguire Seven and Birmingham Six prisoners, all sentenced unjustly for bombing offences in the 1970s. Waddington resisted attempts to reopen the cases, but eventually had to concede an inquiry into the Birmingham Six.

Despite his hardline reputation and unsympathetically brusque broadcasting appearances, Waddington was not relentlessly illiberal. The criminal justice bill he piloted through the House of Commons sought to reduce the prison population by diverting minor offenders to community service orders. He launched a war crimes bill aimed at prosecuting any remaining second world war criminals and a broadcasting act that opened the airwaves to satellite competition, and attempted to liberalise Sunday trading legislation.

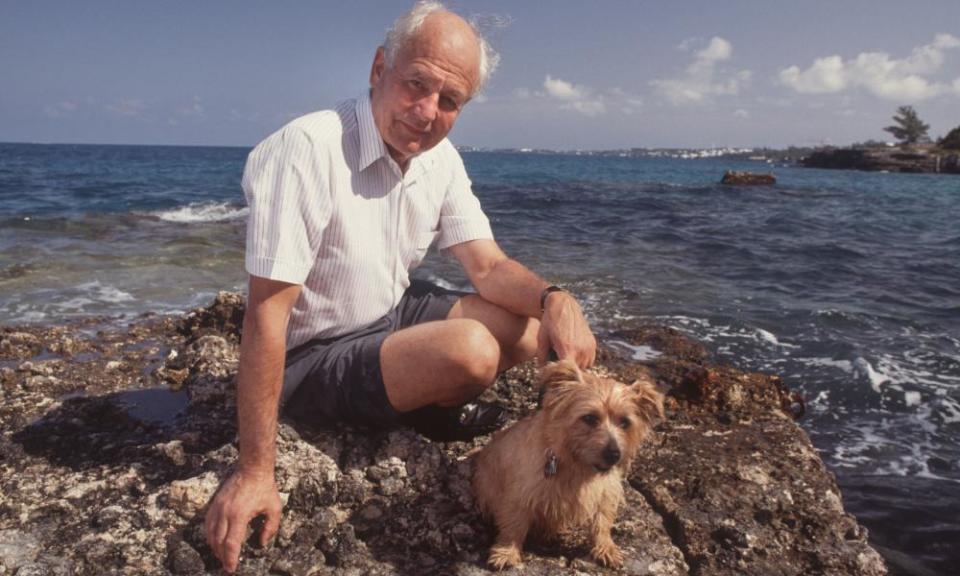

Waddington partly blamed himself for Thatcher’s fall, feeling he had not warned her sufficiently of mounting backbench unrest, and was said to have burst into tears at her last cabinet meeting. He voted for John Major as her successor, but the new prime minister swiftly moved him in 1990 to the House of Lords, to be leader of the government benches there. It was not a happy experience: their lordships were too independent-minded on the contentious issues of Major’s administration, and in 1992 Waddington was moved into the grace-and-favour position of governor and commander-in-chief of Bermuda.

The congenial sinecure allowed plenty of time for sailing and golf, and Waddington claimed that it prolonged his life by 10 years. He and his wife returned to Britain in 1997, and he resumed loyal attendance in the House of Lords. His last significant act there came in 2009, when he promoted a freedom of discussion clause in anti-homophobic legislation, and he retired six years later.

He is survived by Gilly, their three sons and two daughters.

• David Charles Waddington, Lord Waddington, politician, born 2 August 1929; died 23 February 2017

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport