MLB isn’t confident it can produce a consistent ball, leaving GMs to adapt

SCOTTSDALE, Ariz. — Last week at the annual general managers meetings, the state of the baseball — the subtle shift in the aerodynamics that resulted in a not-so-subtle spike in home runs — was a top-level topic of conversation both privately between team executives and in meetings with league representatives.

“Obviously the ball last year, it played differently than it had in prior years,” Phillies GM Matt Klentak said. Data analysis as well as studies of the physical baseball showed that drag on the ball was lower in the regular season, resulting in unprecedented power numbers across the sport and a systematic shattering of home run records — all before the postseason ball doubled back and was shown to be less lively.

A’s GM David Forst agreed that “the science and the evidence is indisputable” that the 2019 ball was different enough to have a material impact on the game — but with a champion already crowned for the season that ended last month, front office focuses have (ostensibly) shifted to building the best team possible for 2020: “Obviously our biggest concern is what is the baseball going to be like going forward and how that affects how we evaluate different players.”

“I can only speak for our organization, but what we want is consistency,” Forst said, “and we’ll build a team around that.”

Unfortunately, that kind of predictability might be impossible to come by — at least before the 2020 season. According to league sources, Major League Baseball is not confident that the ball can be made completely standardized and consistent without overhauling the manufacturing process.

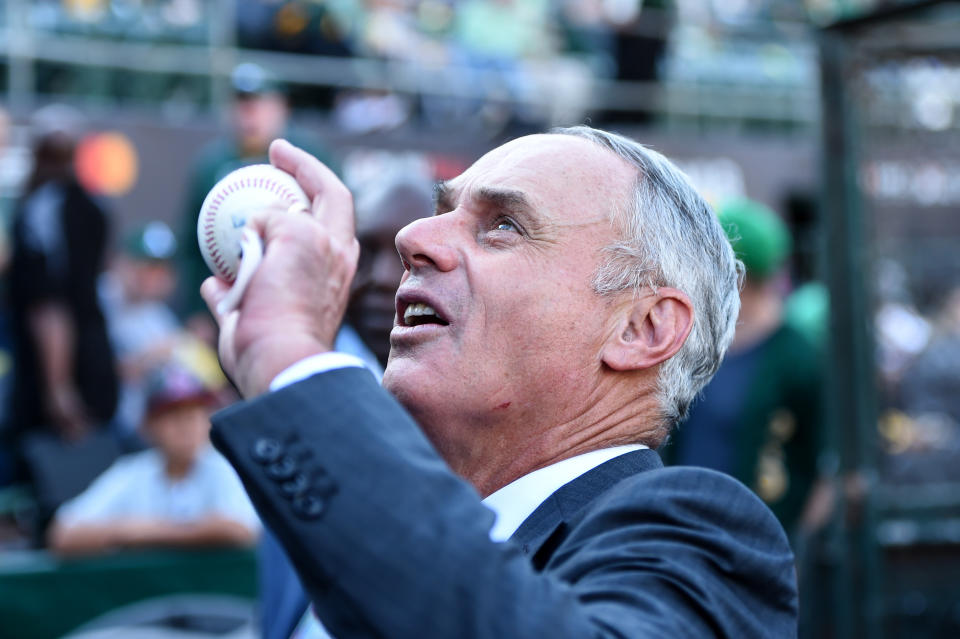

This would mean that any changes in the ball’s so-called juiciness to date were unintentional — as Commissioner Rob Manfred has repeatedly insisted — and that the culprit behind the dramatic swings in drag coefficient the past few years remains a mystery to the league, which also happens to have an ownership stake in the company that produces the baseball. Beyond that, it implies that as long as the balls are handmade and comprised of natural materials, MLB might not ever be able to control to a sufficient degree of precision the behavior of the sport’s fundamental object.

“In terms of roster construction, it definitely matters, you’d like to operate in an environment where the equipment is uniform from year to year,” Klentak said.

The problem with an unpredictable “juiciness” of baseballs is severalfold. There’s the issue of player evaluation, what to make of 2019 power numbers or home runs surrendered and what to project for a particular individual going forward.

“It’s hard to predict just how much of what we see on the field is attributable to the ball,” Angels GM Billy Eppler said.

Rangers GM Jon Daniels compared it (with heavy caveats that the analogy was imperfect for anything other than interpreting data) to the era of rampant PED usage and the ensuing suspicion.

“It’s similar here — how do you evaluate a potential impact on a player’s performance?” he said.

Beyond that, there’s the broader issue of what kind of roster to build — whether to prioritize ground-ball pitchers or bank on 30-homer seasons from undersized middle infielders.

There are more niche and esoteric concerns as well. With the major league ball implemented in Triple-A, home runs at that level skyrocketed in 2019, even as the other minor league levels continued to use a less “juicy” ball. This made for a painful transition for pitchers between levels, confusing farm directors and demoralizing young players.

Our ability to measure fluctuations in the baseball — and understand how that contributes to a particular power environment — is more advanced than it’s ever been. Several GMs cited this increased attention to detail as why we’re even having these conversations.

“So there’s some of that involved,” Forst said, “and maybe there has been variability this much over the years and we’re just now focused on it. Regardless, we’re aware of it now, so we have to deal with it.”

First and foremost, that looks like trying to address the variability. Across the board, GMs professed their faith that MLB was working to do just that.

“Rawlings and MLB, as they work together, they’re not thinking about making the baseballs travel farther or faster, they’re thinking about making them more consistent,” Blue Jays GM Ross Atkins said.

But until then, teams will have to decide if they’re going to ride out the era of wobbly balls by accepting some level of un-optimizable fluctuations — or if they’re going to try to exploit it.

“Now I think if we’re being honest, it affected all 30 teams so it didn’t necessarily create unfair advantages, but I do think that the teams that were able to adjust to it more quickly, were able to see some benefit,” Klentak said.

And “some benefit” is precisely the sort of incremental edge that every GM is looking to find in an age of often equalizing analytics. Klentak’s Phillies are “spending a lot of time researching it,” he said, which is a phenomenon new to 2019 for the team. Whereas, Mike Hazen’s Diamondbacks “don’t think about it all that much.”

“I don’t necessarily feel like we know exactly where the point is that we could make decisions off of it without overcorrecting in some way,” Hazen said.

If anyone does know, they’re not saying. But understanding that the ball might travel different distances depending on the year or month (or even day) is a new frontier in a sport that is running out of market inefficiencies. And while MLB races to eliminate that variability altogether, at least some teams are racing to take advantage of it. As soon as they can figure out how.

“If there is a practical application of that,” Daniels said. “If you figure that out, let me know.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport