From Muhammad Ali to Colin Kaepernick, the proud history of black protest in sport

We may never know why Jake Hepple, a now unemployed welder from Burnley, thought it was a good idea to hire a plane and have it trail a banner reading “White Lives Matter Burnley” across the skies over Manchester’s Etihad Stadium. What we are assured is that Hepple – who has been pictured with his arm wrapped round the shoulder of the English Defence League’s former leader Tommy Robinson, and whose girlfriend was sacked from her job last week, accused of posting racist material on social media (her mother has said her daughter did not write the posts) – was not motivated by any form of racism. After all, he told reporters: “I’ve got lots of black and Asian friends.”

The phrase “white lives matter” is, of course, an attack on the phrase “black lives matter” and the movement that coalesced around it. But while one is a plea for equality, the other, along with the phrase “all lives matter”, was created by those who engage in the pantomime of pretending that anyone is suggesting only black lives matter. These people belong to the same demographic as those who think structural racism doesn’t exist, or that black people should “get over” slavery. And to that demographic, top-flight football’s support of Black Lives Matter really rankles.

The light plane that Hepple hired to pull his banner was timed to appear over the stadium just after kick-off and not long after the players had taken a knee, in memory of George Floyd. The Burnley players, along with their opponents were, like players across the Premier League, also wearing Black Lives Matter badges.

The wearing of BLM badges on playing shirts was proposed by captains from various clubs and highlights how footballers increasingly use their platform to bring attention to social issues. Raheem Sterling has been vocal about media treatment of black players and the lack of non-white coaches and managers in the sport. His England teammate Marcus Rashford recently forced the government into a spectacular U-turn on the issue of free school meals. In a league in which about a third of players are not white, taking the knee was as much an act of solidarity as of political protest.

Kneeling like this was first popularised in the US in 2016 by the NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick. Kaepernick began his protest against systemic racism and police brutality by sitting on the bench rather than standing during the pre-game rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner when he played for the San Francisco 49ers. It was Nick Boyer, a special forces veteran and an ex-NFL player, who suggested that taking a knee was a more respectful but equally powerful protest. This silent, peaceful gesture became a symbol of the Black Lives Matter movement. Last month, it acquired a grim new symbolic meaning, given the nature of George Floyd’s killing.

Kaepernick’s career, and his chance to etch his name into the NFL’s record books, was taken from him. In response to his protest, the owners of the 32 NFL teams effectively colluded to keep him and his teammate Eric Reid out of the league. All of those owners are white and some are Donald Trump supporters and Republican party donors. The US president’s reaction to Kaepernick’s protest was as crude as it was predictable. Speaking at a Republican campaign rally in 2017, he said: “Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say: ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now, out. He’s fired. He’s fired!’”

But Kaepernick was not alone. Months before Trump’s attack on Kaepernick, players in the US Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA), including Maya Moore, had begun their own protest after the deaths of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling. Moore, who some regard as the greatest WNBA player of all time, has since taken two full seasons away from the game, in part to focus on social justice.

And 20 years before Kaepernick and Moore there was the basketball player Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. The fact that his name sparks so little recognition today demonstrates how effectively his career was wrecked after he too engaged in political protest. In the early 90s, Abdul-Rauf was well on his way to becoming one of the NBA’s top players. But in 1996 he refused to stand for the pre-match singing of the US national anthem. He was fined and suspended from the league for 12 games. On his return, he agreed to stand silently during the anthem but to cast his eyes downwards and recite Islamic prayers as a protest against US racism. Even though the NBA had agreed this compromise, and despite the fact that his protest was entirely peaceful, Abdul-Rauf was traded to another team at the end of that season – a move that marked the beginning of the end of his NBA career.

Today, Trump and others feel the need to condemn players such as Kaepernick and Moore because star athletes have reach. The NBA basketball star LeBron James is one of the most recognisable athletes on the planet – with 46.5 million Twitter followers. In Britain, Manchester United’s Marcus Rashford has 3 million, a comparatively modest number, but still more than the prime minister – and considerably more than the foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, who last month said that taking the knee “seems to be taken from the Game of Thrones”. Little wonder, then, that politicians and political commentators seem to get a little antsy when athletes find their voice. When the athletes in question are black – and the issues relate to race and racism – hostility towards them tends to be off the scale.

For parts of the political establishment and sections of the press, in both the US and the UK it seems, black players are OK so long as they are “talking with their feet”, expressing themselves only through their sporting skills and athleticism. Supporting political movements, wearing its symbols or speaking up about racism crosses an invisible line.

In 2018, when LeBron James expressed his views on Trump’s presidency, the Fox News host Laura Ingraham instructed James to “shut up and dribble”. Yet when Drew Brees, a white American football player, offered up his opinion that taking a knee during the national anthem was disrespectful, Ingraham denounced criticism of him as “Stalinist” and “totalitarian”. “He’s allowed to have his view about what kneeling and the flag means to him,” she said.

Ever since the Black Lives Matter protests began to spread across the world, commentators have drawn comparisons between 2020 and 1968, the year Martin Luther King was assassinated and riots and protests tore across the US. Then, as now, sport was not a distraction from politics and the demands for civil rights, but one of the engines driving them forward.

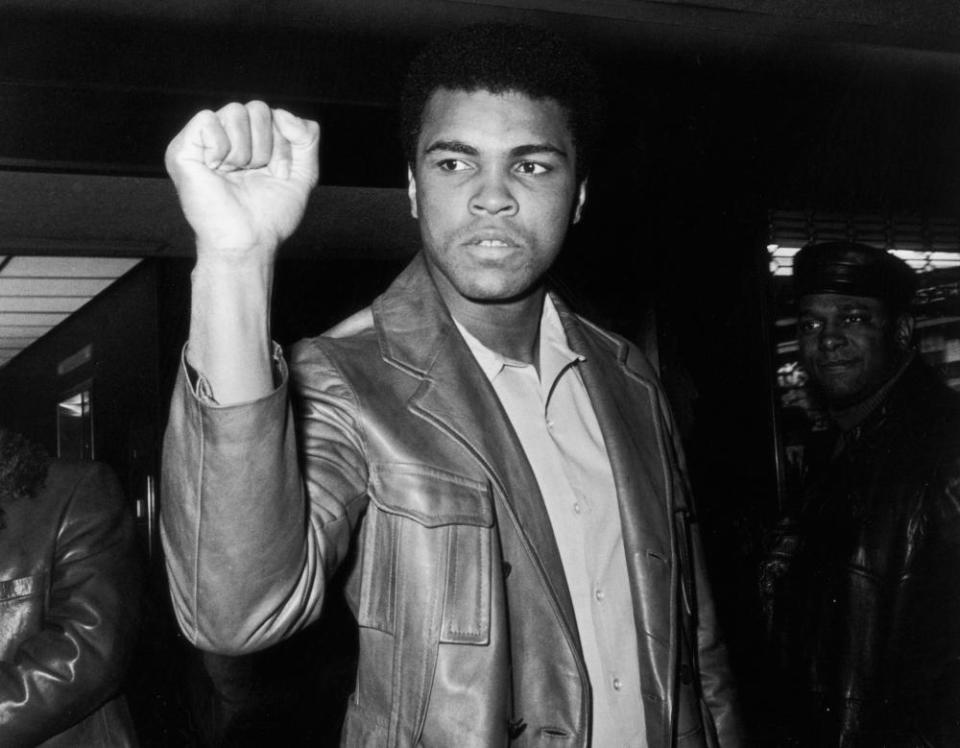

In 1968, Muhammad Ali was not, in the minds of millions of white Americans, a sporting legend but a pariah. The previous year he had refused to be inducted into the US army, then at war in Vietnam. For this he was sentenced to five years in prison (which he did not serve), stripped of his passport and refused a boxing licence in every US state. Ali in 1968 was the embodiment of black political radicalism, but it was Tommie Smith and John Carlos, two US sprinters at the 1968 Mexico Olympic Games, who provided the civil rights movement with its most iconic image.

Smith and Carlos won gold and bronze in the 200m. During the medal ceremony, as The Star-Spangled Banner played, they stood on the podium, shoeless to represent African American poverty, beads around their necks to protest against lynchings, heads bowed and black-gloved fists raised skywards as symbols of black power and unity. That black power fist appears on the Black Lives Matter badges currently being worn by Premier League players. That half a century later the same icon is still needed shows how little progress has been made.

While the parallels between 1968 and 2020 are clear, what is happening now does feel different. In the US, the NFL that ended Kaepernick’s playing career has, in 2020, backed down and will allow players to kneel during the anthem in the upcoming season. In England, the Premier League has given its backing to players who have chosen to take the knee before kick-off. A cynic would say that these are institutions that can feel the shift in public opinion and are simply making shrewd business decisions. The hope has to be that, unlike Smith, Carlos and Ali in 1968 and Kaepernick in 2016, black sportsmen such as Rashford and Sterling will be supported and celebrated rather than vilified for using their voices to fight for social change.

• Peter Olusoga is a senior psychology lecturer at Sheffield Hallam University. His brother David is a historian and broadcaster

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport