A portrait of a Holocaust survivor: behind the scenes at the Imperial War Museum’s landmark exhibition

This is only the third time that Ruth Sands and Jillian Edelstein have met; you’d think they’d known one another for years. At her Belsize Park home, Sands is talking about her life, while Edelstein moves her furniture around. “You know, even when I first came to England, I mean... I thought London was awful. There was nothing there, there was no café... and then it became the city to live in,” Sands says, a wry smile on her face.

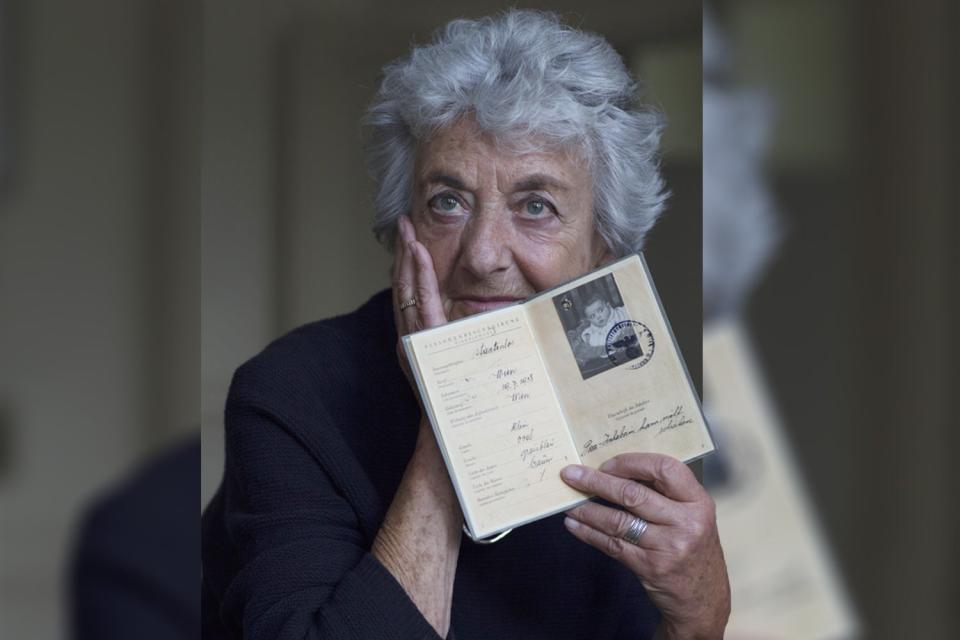

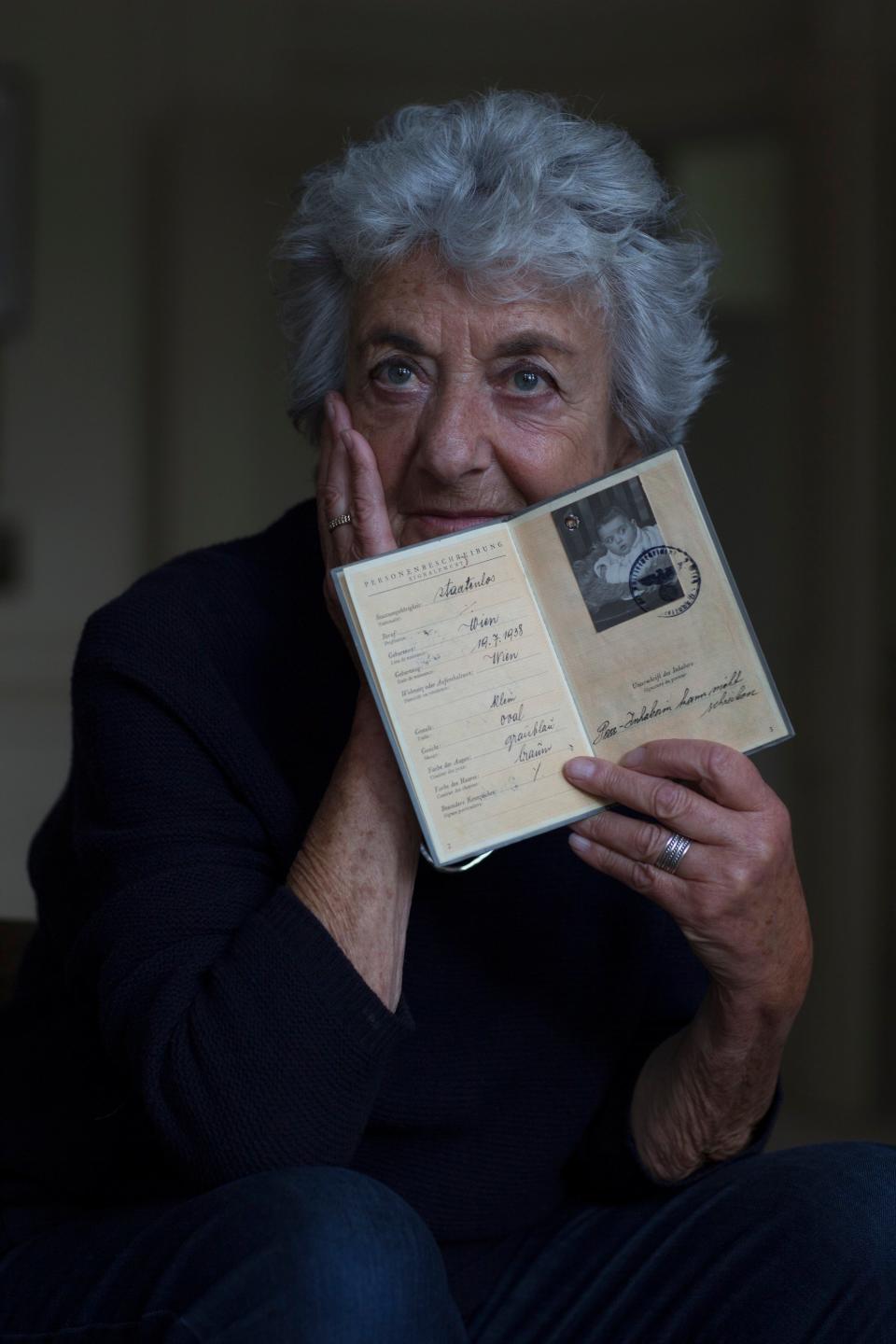

I’m watching Edelstein take Sands’s portrait for a new exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors. Several other photographers, including Sian Bonnell, Hannah Starkey and the Royal Photographic Society’s patron the Duchess of Cambridge, have captured 50 portraits of those whose lives were forever changed by the worst genocide in history, standing alongside their own families, or depicted with objects that are often the only thing left from their early lives. Speaking about the portraits she took of survivors Yvonne Bernstein and Steven Frank in January last year, the Duchess described them as “two of the most life-affirming people that I have had the privilege to meet. They look back on their experiences with sadness but also with gratitude that they were some of the lucky few to make it through. Their stories will stay with me forever.”

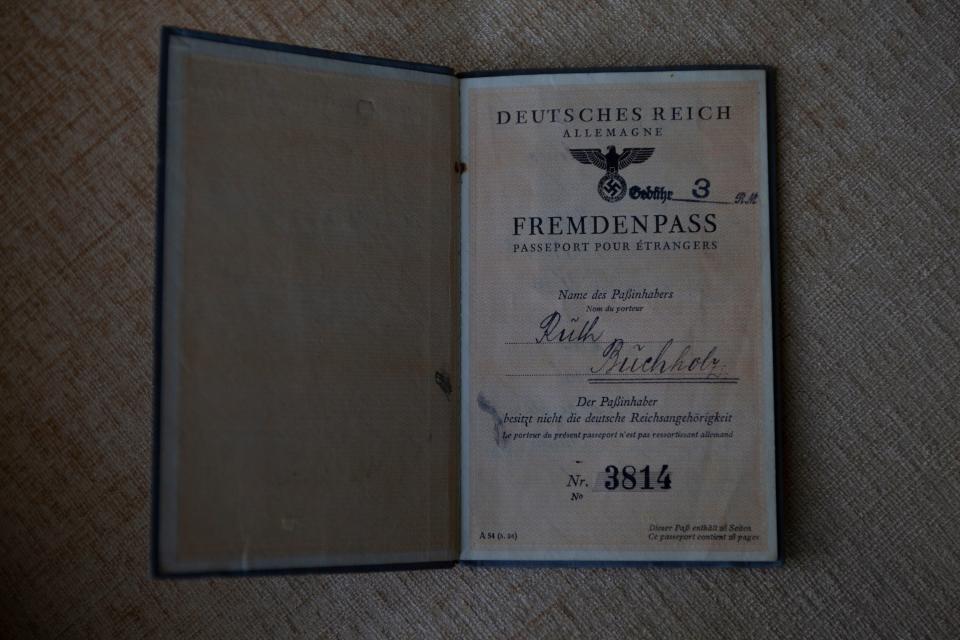

Today, Edelstein is photographing Sands, who has just turned 83, with the passport she was given as a six-month-old living in Vienna, before she was smuggled to France for safety. It’s a disconcerting experience to hold it in your hand: on the front is a Nazi swastika, inside is a black and white picture of a wide-eyed baby. Underneath her photo, where a signature should be, is written in German: The owner of this passport cannot write. “I was six months old. What is the point of writing that the owner of this passport cannot write? I know I’m very clever, but...” says Sands. Her humour is impish, irresistible.

Some may already know something of Sands’s story. Her son, the lawyer and writer Philippe Sands, wrote about it in his best-selling book East West Street. Born in Vienna, she was taken to France when she was just a year old and hidden in Paris for the duration of the war by Christian missionary Elise Tilney. In a sign that she must have been smuggled, her passport does not bear the large stamp of J for Jew that so many others had added to theirs. It wasn’t until the end of the war that she was reunited with her parents. She speaks with an eloquent French accent; as Edelstein photographs her, the pair sometimes slip into French. “Go into a kind of thinking reverie,” Edelstein instructs her. “A rêverie?” Sands replies, Frencher. “A rêverie!” Edelstein says, even Frencher.

Edelstein, who is originally from South Africa and has photographed everyone from Harold Pinter to Amy Winehouse, came up with the idea to shoot her subjects with items from their past because, for those displaced from their homes, “maybe sometimes they replace your kith and kin, somebody very close to you.” Objects have often intrigued her and found their way into her work; when Sands asked Philippe about Edelstein before agreeing to be photographed (he had worked with the photographer when writing his second book The Ratline), he showed her the picture Edelstein had taken of him and John Le Carré eating rhubarb crumble together. Sands was charmed.

“Because you like things,” Sands tells Edelstein, and she holds out her hand to show the ring she is wearing. “When my father left Vienna... it’s his mother’s wedding ring. She never made it overseas. She was murdered. And she gave her son her wedding ring when she said goodbye to him. And my father gave it to me 40 years ago.”

This image of her is for the next generation, too. “One of my grandsons said, ‘Ruth, I want to have a photo of you. I’m sure you’re very glamorous.’ And I say, we organise something... we must have for posterity!” she says, flashing a grin.

But this will be much more than just a portrait of Sands. It will also capture her history, something which carries a legacy of not just loss and trauma but strength and resilience. It’s a collaboration, but also a negotiation; it must feel right. Sands would not want to be photographed with a yellow star, but her Jewish identity has come to matter to her more and more as her life has gone on.

“When people ask me what I am? I didn’t say it when I was 20, but now I say, what am I? Yes, I’m French. Yes, I’m a woman. Yes, I’m all of these. But first and foremost, a Jew. People say, why do you say that? I say, because had I not been a Jew – and, obviously, I make it sound funny – had I not been a Jew, I would have been a well-to-do elderly Viennese woman with a hat on, going to a café, probably very fat because I’m eating too much. My parents came from Vienna and I was born in Vienna, which is a beautiful, magnificent city. And had I not been a Jew, this is where my life would have been. You know? That’s it. That’s why I’m foremost a Jew.”

Later, I ask Edelstein what she wants her portrait of Sands to convey. She thinks for a long time. “I think she’s gone so many incredible strides forward in her life. But I think that passport, it’s not going to define her, but holding that, it must be such a profound... she was a little baby. Somewhere your spirit internalises, I’m sure, that kind of phenomenally impressionable time. And I think all I wanted to do was just get the experience of her being a very strong woman. That’s how I see her. And not being personified by that, but, of course, it echoes back to that time,” she says.

“You can see that she’s got a real joie de vivre,” she continues. “She’s really strong. And she’s very feisty and independent, that’s how I see her, and quite open and direct, and super intelligent, bright. But I think that having that document does just kind of echo back to that time and experience.”

Edelstein’s hope is simply to honour the people she’s photographed. “What you’ve lost you don’t get back easily.” She has also photographed the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa and the Rwandan genocide, and visited many post-conflict countries such as Croatia, Bosnia and El Salvador as part of her work. To her, it’s important “to keep reminding people of what man’s inhumanity to man really looks like.”

Edelstein is meticulous; towards the end of the shoot, she asks Sands to swap the hand she is holding the passport with. “Yeah, this is the best one,” she says, satisfied. “That’s it.”

It almost feels like magic to see the final portrait after spending an hour with the pair of them. It captures Sands’ poise and her intelligence, but also something deeply human. She’s not smiling, but not sad exactly. It shows a woman who has lost things, weathered things, but made a life of her own despite it all. And it’s more surprising still, and actually profoundly moving, that the process of achieving it came from friendship, a connection built from one generation to another in order to benefit us all.

Generations: Portraits of Holocaust Survivors, created in partnership with the Royal Photographic Society, Jewish News, the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust and Dangoor Education, opens at IWM London on August 6; iwm.org.uk

Read More

War Inna Babylon at the ICA review: urgent, haunting and devastating

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport