Sebastian Vettel hits out: 'A slogan is more popular than the truth - look at 'Get Brexit Done'

By any standards, Sebastian Vettel’s swerve from a Formula One paddock to a Question Time studio in Hackney counted as a drastic handbrake turn. The format of the BBC’s premier topical debate show, where guests receive no advance sighting of subjects and where a live audience is primed to extract its pound of flesh, is an automatic no-go zone for many drivers taught to deal only in rehearsed soundbites. For a four-time world champion to submit to such a grilling, in his second language, was enough to make many viewers fall off their chairs.

Except Vettel is long past caring what any sponsors or detractors might think. At 34, he is far removed from the tightly-protected Red Bull prodigy, who, aged 26, became the youngest ever to amass four world titles. Since leaving Ferrari in 2020, he has undergone a political awakening as dramatic as any witnessed in a global sports star. It has encompassed not just a Thursday night alongside Fiona Bruce but a takedown of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, an alliance with the cause of female drivers in Saudi Arabia, and even the wearing of a rainbow “same love” T-shirt to criticise Viktor Orban’s limits on teaching about homosexuality in Hungarian schools.

Vettel was reprimanded for that gesture in Budapest last summer, with the FIA ruling that drivers should avoid political statements during the playing of another nation’s anthem. Clearly, if he is going to mount a full-spectrum assault on his sport’s sensibilities, he had better expect some blowback. When he began his F1 career in 2007, this was a place of deeply conservative attitudes. “Still is, in a way,” he says. But when I ask how he feels about pushing against the status quo, he is undeterred.

“I don’t care,” he replies, after a long pause. “There are topics that are just bigger than the interests of a sport. Formula One is, to me, about the passion for driving the car, about challenging yourself on the edge. But look at the bigger picture: this is also a big business where you’re looking to turn a lot of money around for certain people. To me, that isn’t really important. It feels like a wasted opportunity if you’re not using the platform that we have.”

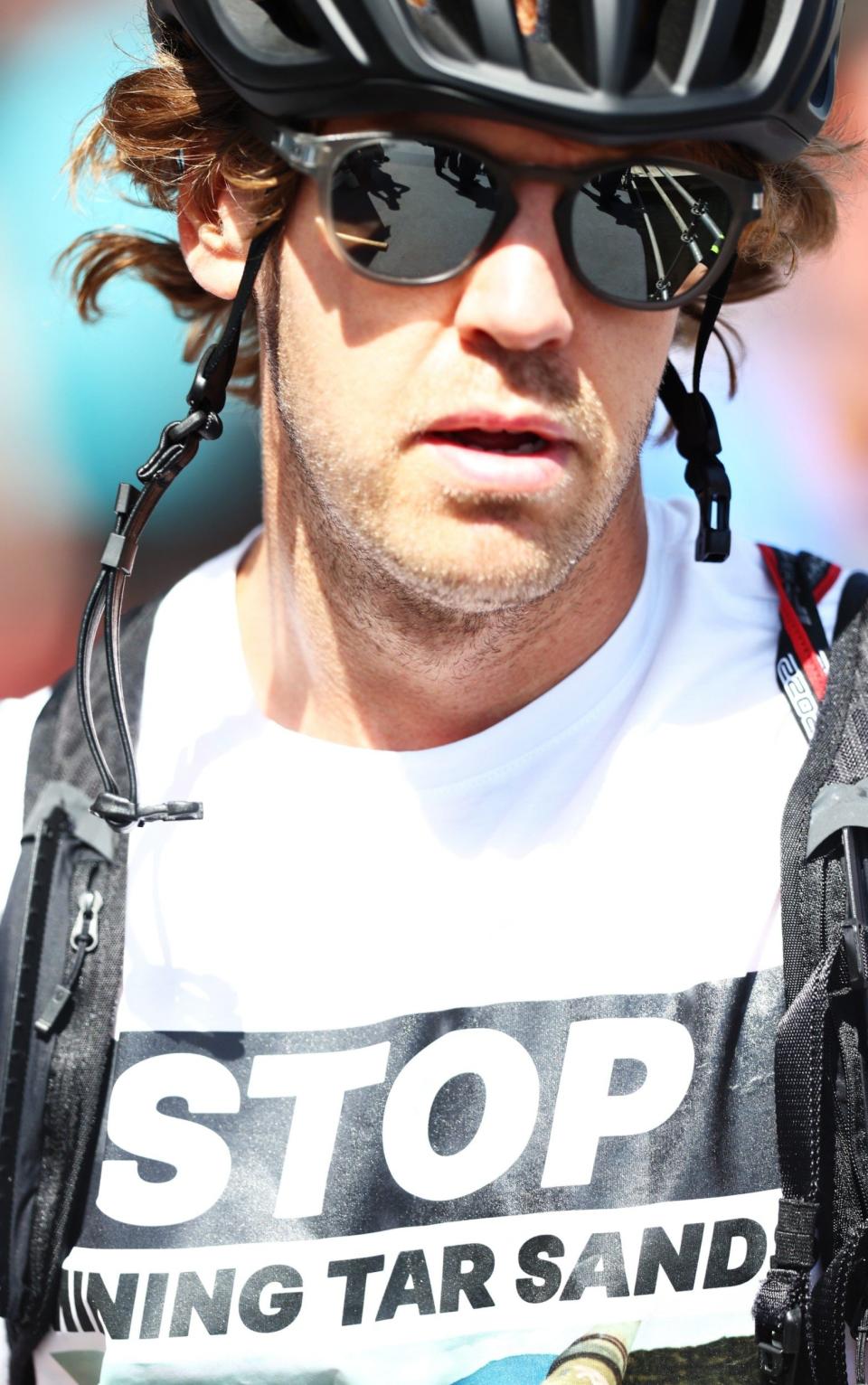

We meet in Montreal, outside his team Aston Martin’s hospitality suite on Ile Notre-Dame. Having grown his hair long, he looks increasingly as if he is cultivating a renegade look. Already, his activist credentials have been on display. Not only did he arrive on a bicycle painted in the colours of the pride flag, he donned a T-shirt condemning Canada’s mining of the Athabasca tar sands in Alberta, the largest and most destructive oil operation in the world.

“I just asked Nicolas Latifi,” he says, referring to a driver eight years his junior at Williams, born here in Quebec. “He is from Canada, he has lived his whole life in Canada, and he doesn’t know anything about it. It’s not to put the finger on Canada and say, ‘Shame on you.’ That’s not the point. It’s about the fact that we all live in a fossil fuels world, and that it will end. The question is when, and how harsh it will be. That was clear 50 years ago – and it’s clear today.”

Vettel’s campaigning extends beyond platitudes. While his sartorial protests might not be to everybody’s taste, he has a record of supporting his words with deeds. In the past year alone, he has led a litter-picking expedition at Silverstone, created fresh habitats for bees in Austria, while becoming the first F1 driver to appear on the front cover of Attitude, underlining his support for the LGBT community. There is, his advisors disclose, another “high-impact” action planned for this week’s British Grand Prix. None of it, he insists, is about chasing popularity.

“Now information travels so fast and changes so quickly, sometimes it’s better to say things that are popular rather than truthful,” he says. “A slogan is more popular than the truth. The truth is harder to explain and less easy to understand. Look at ‘Get Brexit Done.’ It resonates with everyone and people see it as a good idea.”

Vettel was dipping a toe in infested waters with his Brexit verdict on Question Time, observing: “You’re in this mess, now you have to deal with it.” But as he shared a stage with Suella Braverman, the Attorney General, he had sufficient self-awareness not to pretend he had all the answers, or to start accusing politicians on the panel of malign motives.

“You can be very quick to judge politicians and say they’re all bad, or that they’re not honest,” he reflects. “There are a lot who start off with noble goals to make the world a better place. But it sometimes feels to me that along that journey, you adapt and you learn how to cope, that there’s too much political calculation. Then you’re not speaking from your heart. I think it’s a common problem, not just in the UK or in Germany. It’s around the world. It would help if we were not so judgmental, if we just dared to tell the truth a little more. The truth is often not very popular or what people want to hear. But it’s fair.”

A burning question is why, after 15 years in F1, Vettel feels compelled today to reinvent himself as a crusader for truth and justice. Previously, he was known less for his political moonlighting than for his impish sense of mischief, seldom passing up a chance to inflame tensions between Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg at Mercedes. So, why has he chosen this moment to fight for causes far beyond his sport?

“It’s not an overnight thing,” he says. “I agree, it’s very different to what I sounded like 10 years ago. But look at the age on my passport. There is a time and an age for everything. I’m very happy that I discovered these other subjects, because they made my world grow. It now feels very natural to talk about them. Human history is a story of great inventions but also one of exploitation and injustice. These things have to be said, because they are a part of where we are today. It feels like a responsibility. I’m not telling people to buy a certain drink or a certain shirt because it will make me richer. I’m not interested in that. Human rights and the climate crisis are bigger than anything else.”

A crucial factor in these epiphanies is fatherhood. Once, Vettel was so private that he would even shut down any inquiries about his holiday plans. In many ways, his home life in rural Switzerland with his wife Hanna, a former industrial design student whom he has known since childhood, remains a closed book. But here is happy to acknowledge how his three children – Emilie, eight, Matilda, six, and a two-year-old son whose name he has not divulged – have transformed his perspective.

“It does change you, but I believe for the better,” he says. “My kids have helped me to understand that there is so much more, how to experience love in another dimension. It is the most important thing, to look after them and to make them a better version of yourself. I’m in a very privileged position. My job never felt like work – that’s not normal. So, I want to use what life experience I have to help make my kids happy in their lives.”

Few subjects preoccupy Vettel as deeply as ecological destruction. “I’m not an anxious person, but I reach points where I’m very anxious. There’s a term for it: eco-anxiety. For two years the pandemic put a lot of people into misery, but it also distracted a little from the climate crisis that is going on. It will not halt. It will call for more action on our side. We don’t have time to waste. A lot of people don’t have the luxury to read up about this. The younger generation is better. Young people are much more aware than you’d think. You speak to eight-year-olds, they know that littering is bad, that single-use plastics are bad. We need to tell the truth that a large part of our lives is not sustainable.”

The glaring double standard in Vettel’s argument is that he drives a car burning fuel at the rate of 220lbs per hour. He competes in a sport that compels him to visit 21 countries a year, creating a carbon footprint that is positively Godzilla-like. Rather than trying to defend what is, according to his own gospel, indefensible, he confronts the hypocrisy head-on. “You say to yourself, ‘What am I doing? What I’m doing is horrible for the planet,’” he admits. “I had it put to me on Question Time that I’m a first-class hypocrite. But if I stop now, somebody else fills the seat. That’s the way it’s going to go for all of us, independent of what we believe in.”

“You've talked a lot about energy...does that make you a hypocrite?”

“When I get out of the car, of course I’m thinking, is this something that we should do?”

On #bbcqt tonight, F1 driver Sebastian Vettel and the panel discuss the energy crisis.

Join us at 10.40pm on @BBCOne. pic.twitter.com/LVMMs4CuvY— BBC Question Time (@bbcquestiontime) May 12, 2022

The further Vettel pursues his ideology, the more awkward this balancing act is likely to become. On the one hand, he demonstrates his distress about the environment with a sincerity that cannot be confected. In Austria last summer, he was handing out free packets of flower seeds. En route to Monza, he diverted to a plant in Iceland extracting carbon dioxide directly from the air. But on the other hand, he is not about to make himself a martyr. While being a Formula One driver rarely equates to being taken credibly as an eco-warrior, he loves his sport too much to give it up.

It is a stance that leaves him open to criticism. No sooner does he draw attention to the tar sands story in Canada than Sonya Savage, Alberta’s energy minister, responds with derision, tweeting: “I have seen a lot of hypocrisy, but this takes the cake. A race car driver for Aston Martin, with financing from Saudi Aramco, complaining about the oilsands? Perhaps a pedal car for Formula One?” Vettel is not dissuaded by public censure. Where other drivers are obsessed with their portrayals on social media, he scrupulously avoids the noise.

“I’m very happy to learn more and be criticised if I get something wrong, because that might mean next time I get it right. But I’m not worried about criticism that comes anonymously through comments on the internet. Who are these people? If people have the balls to talk to me directly, then fine, I listen to them. But in some chat group online?

“I’m not a researcher, I don’t have the knowledge that scientists do. But if you read just a little, you can connect the dots and see that we are in trouble. It’s about being curious. Maybe that’s the source of it all – I’m curious. Even if we retire the car, I’ll be demanding, ‘Why did we retire it? What broke? What part in the engine? Why did it fatigue? What are the materials?’ It’s exciting to ask questions. ‘Where does that chicken you are having for lunch come from?’ A farm. ‘What type of farm?’ A factory farm. ‘Really? How did those chickens live?’ The world would be a better place if we were asking ourselves more.”

Some of Vettel’s outside interventions have required significant courage. Take his hostility to Vladimir Putin’s Russia, the source of an untold fortune for F1 since Bernie Ecclestone established a grand prix there in 2014. No sooner had the first troops poured into Ukraine on the morning of February 24 than Vettel alone declared he would not turn up in Sochi. It was a boycott with which his sport would soon fall into line.

His tactics towards Saudi Arabia have had to be more creative. The kingdom funnels too much money into F1 for any drivers to risk overtly challenging Mohammed bin Salman. For the inaugural race in Jeddah, Vettel chose instead to run an all-female karting event, heralding the fact that women were finally permitted a driving licence under Saudi law. “You can go to these countries and say bad things about what the regimes are doing, but does it help?” he asks.

“I was thinking there about what we could do to have a more positive impact. It was an ordinary car park, with not very sophisticated go-karts, but that wasn’t the point. It was to celebrate a change, even if that change was far too late and far too little, that women were allowed to drive, whereas their mothers were not.”

An uncharitable interpretation is that Vettel, with any prospect of a fifth world championship all but extinguished, is seeking publicity. And yet he carries a level of conviction to disarm his doubters. “None of this is about me,” he says, firmly. “I couldn’t care less about myself. People are suffering, because of the way they are treated. We fall into the same traps again and again.

“Even if you are a conservative guy, you just need to be truthful. If you say that 20 or 40 years ago, ‘Everything was better,’ well, not really. There’s still much we can improve. Why, then, are we holding ourselves back, holding on to things that are worse? If you imagine London in 20 years’ time, you picture a city where there won’t be so many cars, where public transport will have ramped up like mad. Wouldn’t that be great? No smog, no noise. What are we afraid of?”

Vettel’s restless mind extends even to wondering how he made it to this level at all. His studies of injustice have bred an uncertainty as to why, as the third of four children from Heppenheim, a sleepy market town in central Germany, he ended up as only the fourth F1 driver in history who could call himself a quadruple world champion. “Maybe it’s coming from sport, there’s this sense of fairness,” he says. “If you win and you cheated, you know it’s not fair, because you pushed the other guy down and it doesn’t feel right. Perhaps you can apply the same lesson to life. Maybe I just had better chances than other people and that’s why I’m here.

“There’s an interesting discussion to be had around nature versus nurture. My parents didn’t have the money for this – they found people who helped and paid the bills. Yes, I had to win, otherwise it would have ended right there, but it’s still a privilege to have spent so much time with my parents doing something I love. Not every child has that opportunity.”

Being worried and socially engaged is, Vettel maintains, the logical corollary of growing older. “I ask myself bigger questions now than, ‘Did I win a trophy?’ It’s the same with my friends. Ten to 15 years ago, it was, ‘Which party do we go to?’

“Travelling the world opens your horizons, but only provided you’re looking. You walk the streets of London and it’s so different to the little town I grew up in. You go to the United States and, while it’s praised in so many ways, you look at the poverty and how many people fall off the tracks, how they have no help, no social system that supports them. Who looks after them? To be concerned, it feels like a normal, natural progression, the age that I am.” It is a concern that, given his perpetually inquisitive nature, might never be sated.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport