When things were getting bad for Rod Taylor 'he would point at his head as if to imitate a gun'

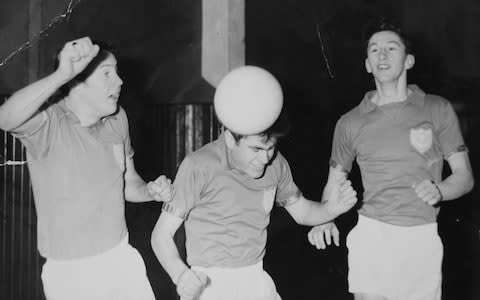

It is when Penny Taylor looks back at a random team photograph from her late husband’s career that the potential scale of football’s problem with dementia becomes so strikingly evident. The picture was taken in the 1960s and she is recalling some of Rod Taylor’s team-mates.

“He’s gone, he’s gone, he’s not well, he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone, he’s gone and he’s gone,” she says, looking sadly at a group of men who should mostly now be in their 70s. She then takes a second look. “Him, him, him, him and him,” she says, shaking her head. “Half of them had dementia.”

It is similar with other teams from that era and, behind these young faces, there is often an inspiring but ultimately heartbreaking story of the realisation of a boyhood footballing dream before later life is prematurely destroyed by dementia.

Having been born in the Dorset village of Corfe Mullen, Rod was 15 when he joined the ground staff at Portsmouth during an era in which they were among the giants of English football. He would soon meet Penny and they have two children, Rachel and Spencer. Rod cleaned the legendary Jimmy Dickinson’s boots.

He was in the Portsmouth reserve team who were the first to play Manchester United after the Munich air disaster in 1958 and, as a wing-half during spells at Portsmouth, Gillingham and Bournemouth, faced the likes of Alan Ball, Sir Geoff Hurst, Sir Stanley Matthews and John Charles.

He later continued playing in non-League until he was 50 for Poole Town, Andover and Ringwood before becoming a builder and decorator.

Pick a Telegraph Fantasy Football team now for the chance to win a share of more than £100,000 >>

“Football was Dad’s obsession,” says Rachel. “He was delighted when I bought a house near Fratton Park. He would have a cup of tea, walk to the game, come back for more tea and cake before driving back to Dorset.”

There had been subtle changes of behaviour since 2008 but the first really alarming incident was in 2010. Penny had spent eight weeks at the Royal Marsden Hospital following a cancer diagnosis.

The family were visiting daily but Rod, now in his mid-60s, would generally take the lift to her ward because his knees were so badly damaged by football. “I was waiting for him at the bottom and he didn’t arrive,” says Rachel. “He got completely confused and disorientated. We could not find him for about 20 minutes. At the time, I put it down to Mum being ill and him being tired and stressed.”

Rod, though, would become more emotional and forgetful. There would be swings of mood. His judgment and spatial awareness were impaired. A hip operation in 2014 was especially traumatic. “He didn’t know where he was or what he was doing – he had delirium,” says Rachel.

The decline was initially steady but, when he became unable to reverse out of a driveway, it was clear he could no longer be allowed to drive. He stopped wanting to go to Fratton Park in 2016 and, during the final 18 months, his dementia accelerated aggressively.

“Mum struggled on but I don’t know how,” says Rachel. “He would fall, be up all night, get hallucinations. It was 24/7. He hated what was happening. When things were getting bad, he would point at his head with his two fingers as if to imitate a gun. Mum developed Parkinson’s, I think, through looking after Dad. We were pleading with her to get help. I thought I would lose not only my dad but also my mum.”

A day of respite care was organised but that was soon insufficient. Funding, at £1,600 a week, was necessary for full-time dementia care and, with football not meeting this need among many of its former players, social services did provide crucial assistance.

Rod was admitted to respite care at the end of March but, within days, the family arrived for a visit to find an ambulance outside the home.

“Dad was on the floor, needing oxygen and had broken his hip,” says Rachel. “He was in heart failure and had advanced dementia.”

Rod could no longer speak or swallow and would also develop pneumonia and sepsis. After just over two weeks at Poole Hospital, he died on April 16. “Nothing prepares you for the end stages of dementia,” says Rachel. “He was 74 but looked like he was 94. Mum was with him. He took one last look at her and off he went.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport