Trump's wink toward white supremacism raises the age-old question: Which side are you on?

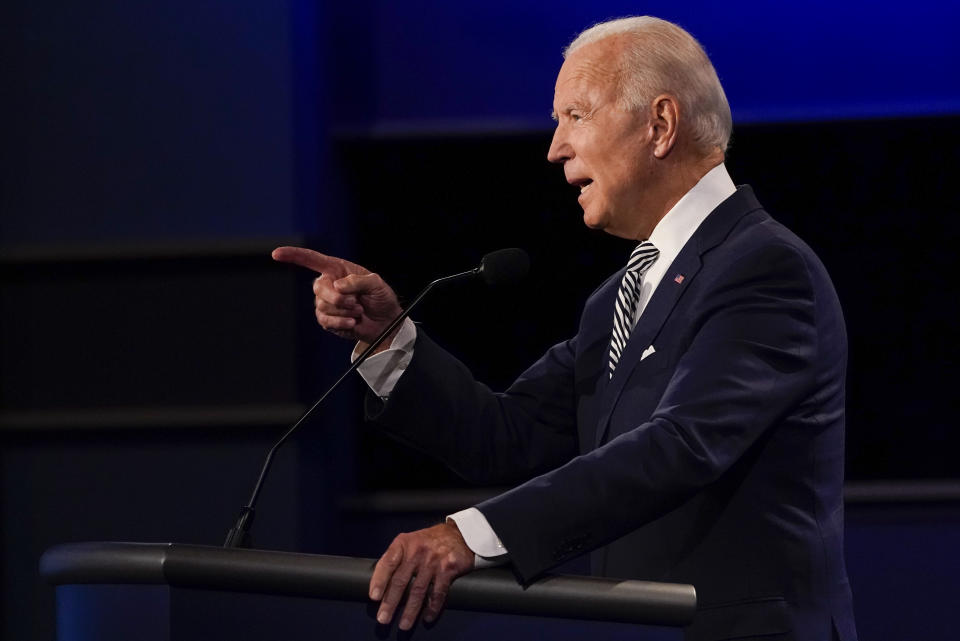

Van Jones, the prominent African-American political commentator on CNN, was apoplectic. Like millions of other Americans watching the first presidential debate between President Trump and his Democratic challenger, former Vice President Joseph Biden, Jones, 52, an environmental and progressive activist who served in the Obama administration, just witnessed an extraordinary moment in America’s tortured racial timeline.

The president had not only just refused to denounce the Proud Boys, a violence-prone modern-day white supremacist group that aligns with him, but he called on them to “stand back and stand by,” in case he needed them in the upcoming election.

As Trump has done throughout his presidency, he managed, apparently in desperation, to stumble, hair on fire, into a ticking bomb. It struck Jones as tantamount to a call to arms to a group that personified the sordid history of racist mob violence in America. It sounded like that to me, too.

“Only three things happened for me tonight,” Jones said. “No. 1, Donald Trump refused to condemn white supremacy. No. 2, the president of the United States refused to condemn white supremacists, and No. 3, the commander in chief refused to condemn white supremacy.”

Speaking live on air, Jones fretted about the effect on his children of seeing images of hate-motivated violence. He later tweeted: “I have a friend of color whose son watched this, turned to his mom, and asked if they should buy a gun to protect themselves. We are beyond politics at that point. We are in a moral swamp, watching behavior from the president that would not be tolerated in a kindergarten class.”

I hesitate to even type such an honest sentiment, knowing Trump’s penchant for turning a cry for help from your government by a Black person into something that stokes derision and irrational fear in some white Americans.

“Wouldn’t you love to see one of these NFL owners, when somebody disrespects our flag, to say, ‘Get that son of a bitch off the field right now,’” the president intoned before a Huntsville, Ala., audience in September 2017, seeking to turn the cry of pain from a Black athlete over the deaths of unarmed Black men and women into a completely false and ugly anti-patriotic smear that anticipated and helped set the stage for the racial crisis the country has been in for the last six months.

Through a clear lens, both as a Black man with Southern roots and a reporter, I know that Black people have always had to arm themselves against racist night riders.

White supremacists bandy about the meaningless term “race war,” an apocalyptic term that falsely implies a struggle fought on equal terms. But historically, they haven’t waged “war” on African-Americans but perpetrated naked terrorism on people without much ability to fight back. In the Wilmington, N.C., riots of 1897, the 1906 Atlanta riots, the “Red Summer” of 1917 when over 250 African-Americans were killed, the attacks on the “Black Wall Street” of Tulsa, Okla., in 1921, and Rosewood, Fla., in 1923, white mobs simply raged through Black communities, forcing people to fight or die.

When I was growing up in Mississippi in the 1950s and 1960s, my father and his friends were hunters who regularly kept guns cleaned and ready for use. It was also understood that as there was no expectation that local or state authorities could be depended on to protect us from white mob rule, these guns could also be pressed into service to defend home and hearth. Home from college in the summer of 1965, I vividly remember when Ku Klux Klan terrorists bombed the truck of local NAACP leader George Metcalfe, seriously injuring him and sparking the formation of a group of armed Black men known as the Deacons for Self Defense.

Barely a year later, in January 1966, the home and store of Hattiesburg NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer Sr. was firebombed by a raiding party of Ku Klux Klansmen. Dahmer kept the attackers at bay by firing his own weapons out a window while his wife and two young children escaped their burning house. Dahmer later died from his injuries. Four of his sons, dressed in their military uniforms, are captured viewing the ruins of the family home in an image taken by photographer Chris McNair, whose 11-year-old daughter, Denise, had been one of the four little girls killed in the Birmingham 16th Street Church bombing in 1963.

As veteran civil rights worker and journalist Charles Cobb Jr. observes in his book “This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible,” Martin Luther King Jr. recognized the need of Black Southerners to protect themselves as well as him.

“The facts that guns were present inside King’s (Montgomery, Ala.) home and were carried by the neighbors who took turns guarding his family and property should not be surprising,” Cobb writes. “The easiest way to understand this is to begin with the basic fact that Black people are human beings, so Black people’s response to terrorist attacks are the same as anyone else’s.”

What makes this moment so fraught is that in times past, when local and state governments stood aside while white mobs publicly attacked even Black children, we could expect the might of the federal government to restore law and order regardless of party. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, a Republican, sent in the 82nd Airborne Division to protect nine Black students attempting to enroll at Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., in 1957. Democratic President John F. Kennedy sent federal forces to Alabama in 1961 and Mississippi in 1962 to ensure the peaceful enrollment of Black college students to previously all-white universities.

As he did with the coronavirus, which sadly has struck inside his own family and White House, President Trump has downplayed the rising virus of white-nationalist-related violence since his election, even as his own administration has sought to warn us. On the same day that the FBI issued an intelligence report warning of an imminent “violent extremist threat” posed by far-right militia that includes white supremacists, first reported by the Nation, Trump insisted, “Almost everything I see is from the left wing, not the right wing.”

When Biden pushed back that FBI Director Christopher Wray, Trump’s own appointee, had endorsed the report, Trump shot back, “He’s wrong.”

Trump belatedly tried to walk back his explosive comment days later with his characteristic meaningless hyperbole, asserting that he had “condemned white supremacy more than any other president.” But the message seemed to have landed loud and clear among its intended audience. Amazon quickly removed from its site Proud Boys merchandise emblazoned with the president’s words: “Stand down and stand by.”

The most important thing that any leader can do in a crisis is set the right tone. Now, absent that, like a biblical parable, with the FBI warning that a “potential flashpoint” of right-wing extremist violence exists through the final days of the 2020 election up to the inauguration of 2021, America stands at the same crossroads it has many times since the Civil War, and Americans face the same existential question they did when Alabama lawmen on horseback waded into the crowd of marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965, bloodying, among others, the future congressman John Lewis.

It is the question that rang through Black churches throughout the South, in the words of an old Pete Seeger folk song delivered like a hymn by people willing to face the wrath of white supremacists just to register to vote: “Which side are you on?”

_____

Read more from Yahoo News:

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport