The year in VAR: from World Cup guinea pigs to Premier League fury

The year in VAR begins in June, at the Parc des Princes in Paris. Scotland are on the verge of qualifying for the last 16 of their first ever Women’s World Cup. They are 3-2 up and the match is in the 90th minute when a penalty is awarded to Argentina. Florencia Bonsegundo steps up to take and … it’s saved! And the follow-up too! But Scotland’s goalkeeper Lee Alexander does not celebrate, she just gets up and glares.

It turned out that was the right decision. Within a minute Alexander’s heroics had been snuffed out. A VAR check of the penalty revealed that Alexander’s feet had stepped off the goalline, her back foot by a matter of an inch, and the kick was ordered to be retaken. Bonsegundo took her second chance and a draw was not enough: Scotland were going home.

The incident went on to become a source of great controversy. The England goalkeeper, Karen Bardsley, described the decision against Alexander as “cruel and pedantic” while the former US keeper Hope Solo, writing in the Guardian, lambasted the use of video refereeing technology in the World Cup as a whole. “VAR has been so frustrating throughout this tournament,” she said. “Women were used as guinea pigs.”

Related: VAR should only be used for 'clear and obvious' offside errors, say law makers

Those complaints from the French summer ring true in England in winter. Since the Premier League introduced VAR at the start of the season there have been important, game-changing decisions that have seemed highly pedantic; moments decided by the width of an armpit. The technology has been applied inconsistently (and slowly) by people with limited experience. As for new rules that have not helped matters, try on the handball law for size.

In November, during a notably bullish presentation about VAR’s first few months, the Premier League’s refereeing chief, Mike Riley, admitted to the technology having made four errors. One of them seemed to capture all the aspects of VAR that have proved contentious: a goal scored by Sokratis Papastathopoulos for Arsenal against Crystal Palace.

The score was 2-2 and the match entering its final period when the centre-half smashed in what looked like a winning goal from a corner. It was scrappy, a Nicolas Pépé kick flicked on at the near post into a crowd on the edge of the six-yard box, before spilling out to Papastathopoulos 10 yards out. His shot crossed the goalline at 82:18. Only when the clock hit 84.15 did the referee, Martin Atkinson, rule it out, for a perceived foul by Arsenal’s Callum Chambers in the buildup.

Riley would later admit that Chambers had committed no such foul. But for fans – especially those in the stadium – that was little consolation. They had been denied a goal and potentially two league points. They had also endured the mortifying experience of having celebrated a goal that turned out never to have happened. The final indignity was that the decision to overturn took two minutes to make, a period that can feel like a lifetime in a stadium. The question many fans were asking was this: even if there had been a foul (which there had not) if it took two minutes to spot with a bank of video screens at your disposal, could the referee’s mistake really have been “clear and obvious”?

Clear and obvious, clear and obvious. During the autumn those three words were repeated more often than “boy done good”. This was the high bar the Premier League had set itself, the criterion any incident would have to fulfil before the VAR would intervene in a referee’s decision. Alongside the original motto for the technology – minimum interference for maximum benefit – it seemed simple and straightforward enough.

But it did not turn out like that. One problem with “clear and obvious” was that it was not supposed to apply in every situation. In decisions regarding offside or handball there was nothing subjective about it, according to Riley and co. So, if a decision was marginally wrong, it was still wrong and should be overturned.

This led to initial confusion among fans and pundits alike. The same could be said of the phrase more broadly, with many people thinking a moment that was, say, clearly and obviously a foul, should require the VAR’s involvement when, in fact, it was only if the referee had made a clear and obvious error in not seeing it.

That VARs themselves should interpret what was “clear and obvious” in a number of different ways should not, therefore, have proved surprising. But they did and sometimes it would result in minutes spent poring over details (see PastathopoulousPapastathopoulos’s goal) before coming to a conclusion that might flip a match on its head. VARs and the “video operatives” working alongside them also had varying levels of aptitude in applying the technology at their disposal. New 3D representations of an offside decision could take an age to be crafted, something that became even more frustrating when it turned out the cameras that had taken the original pictures were not fast enough to capture split-second actions in the first place.

Fans in the ground rarely got to see these images; they were more often served up on TV. And it was the match-going fan who really got the short straw in VAR’s first few months. The rules, mostly established not by the Premier League but by the International Football Association Board (Ifab), which oversees the laws of the game, prevented footage being shown unless a decision had already been overturned. The body also prevented the crowd from receiving any communication from the referee. Fans were not only left sitting in a state of frustrated limbo for minutes at a time but often had no clue as to why.

Amid all this frustration the fact that VAR had significantly improved the number of correct decisions (reducing what they call errors in Key Match Incidents from 47 by November 2018 to 24 at the same point in 2019) was by the by. Come November the Premier League went into listening mode, meeting fans groups and stakeholder clubs. Changes were promised. Big ones would have to wait for Ifab but small ones arrived in time for Christmas.

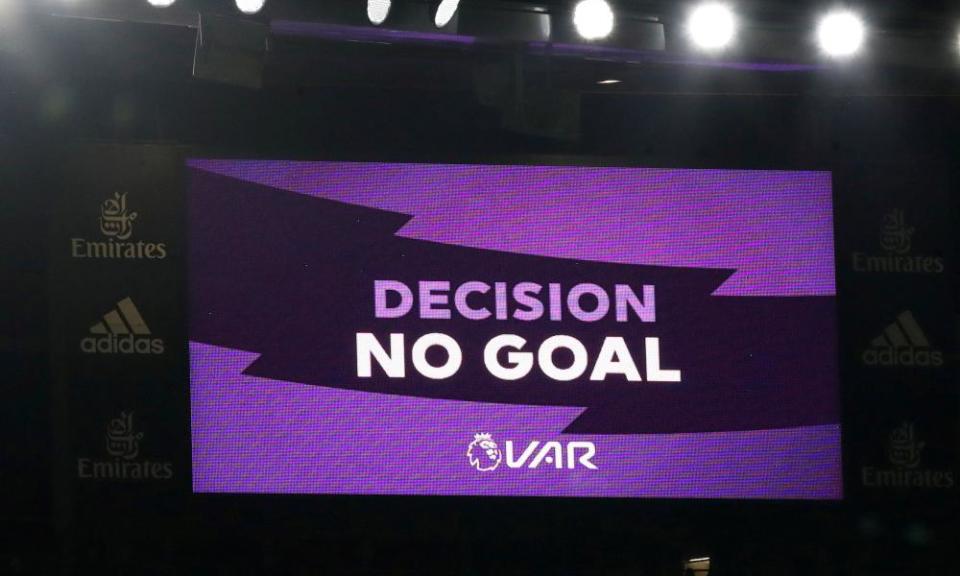

Now at a Premier League match (at any ground bar Old Trafford and Anfield as they do not have big screens), when the VAR is in operation, the crowd are not just informed but given a reason why: “VAR checking penalty – possible handball” being one such example. It’s a small step but when it’s applied in the ground the response is at least no longer one of incandescence. All people want is to understand what is happening.

VAR may be here to stay but it seems fair to say there is more learning to be done before it can be called the finished item.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport