Virginia school district bans 2 classic American novels for racial slurs

A school district in Virginia temporarily suspended the use of two classic American novels after a concerned mother complained about the racial slurs in them.

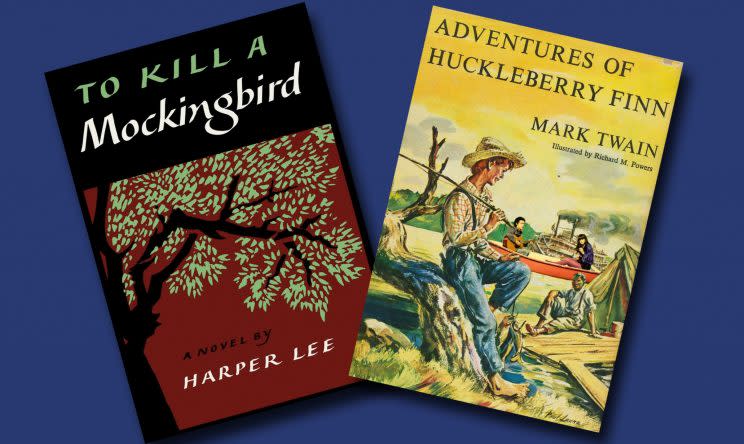

The novels in question are “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee and “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain. Scholars hold both books in high regard for their literary merit and the anti-racist themes that were progressive for their respective eras.

Nevertheless, both novels have been repeatedly challenged in school libraries over the years for the books’ frequent use of the N word, which appears 219 times in “Huckleberry Finn” and 48 times in “To Kill a Mockingbird.” Both books rank among the most banned and challenged in U.S. history.

In the latest case, a parent of a child in Accomack County Public Schools filed a “Request for Reconsideration of Learning Resources” form challenging the use of both books in the school curriculum after speaking at a school board meeting last month, CBS affiliate WTVR reported Thursday.

On Nov. 15, she told the school board that her child is biracial and that he’s having trouble reading past one page that has the N word on it seven times. She suggested that the students read other books because assigning “Huckleberry Finn,” she argued, “validates that these words are acceptable.”

“I keep hearing ‘This is a classic, this is a classic.’ I understand that … but at some point I feel the children do not truly get the classic part … but there are so much racial slurs in there and offensive wording that you can’t get past that,” the mother can be heard saying in an audio recording of the meeting. “Right now, our nation is divided as it is. I teach my son he is the best of both worlds, and I do not want him to feel otherwise.”

The superintendent for Accomack County Public Schools did not respond to a request for comment from Yahoo News.

Roger Lathbury, a professor of English at George Mason University, said the N word was freely used in many 19th-century books and even in early 20th-century ones.

“That the word did not have the same racial charge in the 19th century, when Twain wrote, does not count for the banners,” he told Yahoo News on Friday. “That partly is understandable, because grade school and high school students usually do not read with a sophisticated historical sense; on the other hand, it is simplistic thinking.”

Lathbury, who specializes in early American fiction and modern British poetry, pointed out that “Huckleberry Finn” was banned in Boston and elsewhere when it was first published in the U.S. in 1885 for reasons that had nothing to do with racial slurs.

“The reason was that Huckleberry Finn was judged to be too low-class for literature, too rough and uncivilized a person for readers to focus on,” he said. “Of course, that is exactly Twain’s point — to be ‘sivilized’ is to be on the wrong side of human values — but the banners did not redline the book for that reason; they wanted a more acceptable hero, closer to Tom Sawyer.”

The American Library Association (ALA), a pro-library nonprofit that promotes freedom of expression, says books are usually challenged on the grounds of shielding children from sexual content or offensive language, which was the case in Accomack County.

According to the ALA’s “Library Bill of Rights,” librarians and governing bodies should respect that only parents have the right to restrict their own children’s access to library resources. The organization maintains that libraries violate the First Amendment if they censor constitutionally protected speech.

Some people have attempted to thread the needle on the controversy. In 2011, professor Alan Gribben sparked widespread controversy when he announced that he would publish expurgated versions of “Huckleberry Finn” and “The Adventures of Tom Sawyer,” another Twain book that uses the N word.

In the forward to this edition, Gribben explained that he has given instruction on both books for nearly 40 years and would always recoil from uttering the racial epithet during his lessons. He started to substitute other words for the N word to the students’ relief and wanted to provide an alternative edition for teachers who felt uncomfortable with the word but did not want to abandon Twain’s masterpiece altogether.

“I invariably substituted the word ‘slave’ for Twain’s ubiquitous N word whenever I read any passages aloud,” he wrote. “Students and audience members seemed to prefer this expedient, and I could detect a visible sense of relief each time, as though a nagging problem with the text had been addressed. Indeed, numerous communities currently ban Huckleberry Finn as required reading in public schools owing to its offensive racial language and have quietly moved the title to voluntary reading lists.”

The reaction was fiercely divided. Many argued that readers cannot fully comprehend the evils of slavery if texts that realistically depict the era are bowdlerized. But Gribben maintained that it is preferable to salvage the text, which is central to the history of American literature, than to have it banned in various public schools.

After all, author Ernest Hemingway once famously said, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ American writing comes from that. There was nothing before. There has been nothing as good since.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport