Yes, Andy Murray is a decent feminist ally, but tackling sexism in sport will take a lot more than one outspoken tennis player

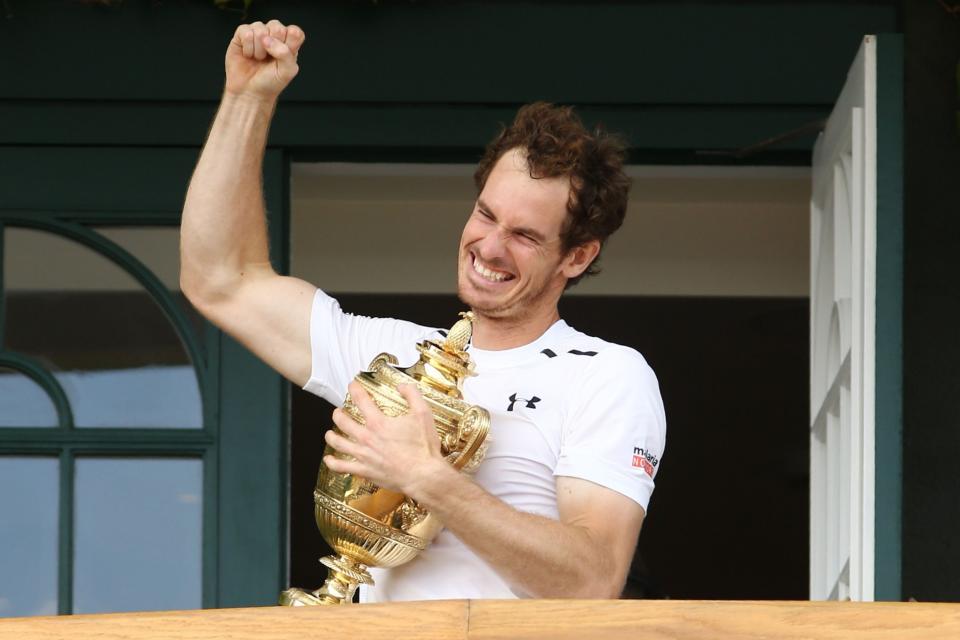

This morning I was greeted by the news that Andy Murray was retiring from tennis by the end of Wimbledon, if not before. It means the loss of a great tennis player, but – as many have pointed out – it also means the loss of a vocal feminist male tennis player.

Billie Jean King, 12-time grand slam champion and early proponent of women’s tennis tweeted: “You are a champion on and off the court. So sorry you cannot retire on your own terms, but remember to look to the future. Your greatest impact on the world may be yet to come. Your voice for equality will inspire future generations. Much love to you & your family.”

Murray’s 2017 comment to the journalist who called Sam Querrey the "first US player" to reach a major semi-final since 2009 has once again been doing the rounds of Twitter, as Murray rightly pointed out that there had been plenty of success from the female players. The video strikes a chord because his feminism expresses itself so authentically and simply. He is known as a man of few words, only needing two to demonstrate the sexism inherent in the journalist’s question: “male player”. Murray has previously interjected in a similar fashion when John Inverdale cavalierly conflated “person” with “man” while discussed the Olympic gold medals that American players had won.

I particularly admire that Murray is not afraid to admit that he had blind spots with regards to sexism. Following his hiring of Amelie Mauresmo as his coach, he said that he didn’t realise the extent of the abuse she would receive. He only realised later in his career that it was normal for men to coach women but never the other way around. This plays into the fact that in 2011 just 24 per cent of 1,652 licenced UK coaches were women.

Serena Williams has praised Murray for his feminist stances, telling ESPN in 2016: "I don't think there's a woman player – and there really shouldn't be a female athlete – that is not totally supportive of Andy Murray.” However, there is only so much one person can do, especially when so many other people (not just men, but also women) seek to uphold the status quo of sexism in tennis.

Judy Murray, previous Fed Cup captain and mother to Andy and Jamie Murray, has spoken out about how far tennis still has to go to achieve gender equality. Last December she wrote an article for The Guardian detailing the impact that a coaching event held for women in sport had had on her confidence, demonstrating the importance and continued need for such initiatives. She has also recently said that tennis is due its own #MeToo movement.

Equal prize money at every grand slam is great. Yet it only a recent development: Wimbledon instituted equal prize money in 2007 – 37 years after the Equal Pay Act. As Andy Murray has himself commented: “I just don’t get is why it wouldn’t be something that tennis players are proud of, like, to be the only sport [where earnings] are even comparable…”

While Murray is quite right to use his platform to support women, it seems astonishing that the bar is set so low that he is hailed as a feminist hero simply for pointing out that women should be paid and recognised equally to their male counterparts. Sports as a whole has a woefully long way to go before achieving even these very basic tenets of gender equality. Within tennis alone, Serena Williams has been subject to sexism for everything from her outfit choices to having human emotions.

The worrying thing is that the reasons given for sexism in tennis (and sport, more generally) are still the same. Rafael Nadal, Novak Djokovic and Raymond Moore, the CEO of the Indian Wells tournament, have all commented that women should not earn as much as men as the men as they do not attract the same numbers of spectators. The BBC Sport Twitter account rightly drew criticism for implying that Serena Williams did not deserve her prize money as her match was so short.

Tennis may have equal pay and one or two outspoken male feminist allies, such as Andy Murray, but the underlying sexist assumption that women players do not deserve what they get needs to be tackled now more than ever.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport