The $7bn bet that couldn’t lose: how Vegas became America’s sports capital

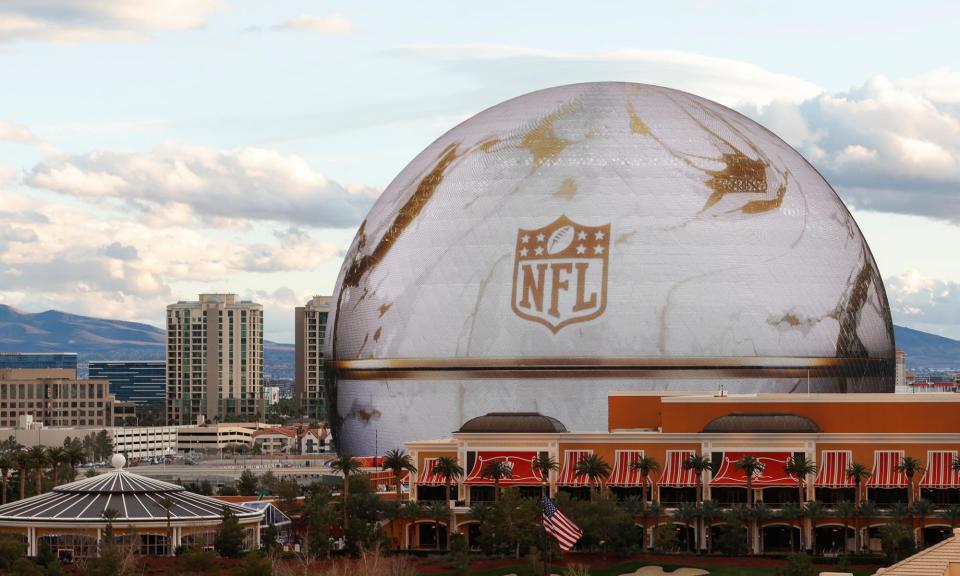

Sidewalks and overpasses festooned with red and purple signage. Corporate installations and official merchandise stands still being erected. Sprawling casino floors filled with fans clad in football jerseys, huddled around table games and feeding bills into NFL-branded slot machines. The first Super Bowl to be played in Las Vegas was still days away, but the signposts of America’s high holy day were already in full view on a drizzly Monday afternoon up and down the famous Strip.

They were scenes that would have been unthinkable even a decade ago, when the major US professional sports leagues – none more than the NFL – uniformly shunned Vegas for its associations with gambling culture. But when the San Francisco 49ers and Kansas City Chiefs kick off the nation’s biggest sporting event on Sunday at Allegiant Stadium, it will mark the culmination of a city’s improbable rebranding from old gambling town to America’s sports capital.

Over the past calendar year, a locale once verboten to major sports outside big prizefights has played host to the NBA’s Summer League and In-Season Tournament finals, a Formula One grand prix, and the Sweet 16 and Elite Eight of the men’s NCAA basketball tournament. College football’s national championship game and the men’s Final Four are up next. In the span of less than a decade, Las Vegas has become the home of the NFL’s Raiders, the NHL’s Golden Knights (who have already won one title) and the WNBA’s Aces (the last two on the trot). Major League Baseball’s Athletics are already in the process of relocating from Oakland, while an NBA expansion team with an estimated value of $6bn is widely expected to follow with LeBron James openly campaigning for ownership. No city this side of Riyadh is hoovering up sports properties at a faster clip.

But no event signals Las Vegas’s arrival as a sporting mecca quite like the Super Bowl, the all-conquering pan-cultural event for a league which for decades had kept Sin City at arm’s length. Nearly $7bn has been committed to transforming Vegas into a global sports hub in recent years, according to a Bloomberg estimate, which has included the construction of state-of-the-art stadiums and arenas. That figure also accounts for eye-watering tax breaks: no less than $750m of the $1.2bn price tag for Allegiant Stadium was funded by Clark County hotel room taxes, then a record amount of public funding for a football stadium. But few can dispute the return on investment if the expected $500m economic impact from this week’s Super Bowl proffered by the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority is even close to the mark.

“We are the sports capital of the world right now,” said Oscar Goodman, the former mob lawyer turned Las Vegas mayor from 1999 through 2011, who tried for years to bring professional sports to town. “If there isn’t a sport here yet, we will have it in a couple of years.”

For decades America’s pro leagues adhered to the firewall between gambling and sports, one borne from the nation’s puritanical roots and erected in the face of existential crisis amid the 1919 Black Sox scandal. That bulwark was only reinforced with each passing generation’s betting imbroglio: the CCNY point-shaving episode, Tulane basketball, Pete Rose and Tim Donaghy. The NFL’s resolve to insulate football from sports betting redoubled in 1963, when Green Bay Packers halfback Paul Hornung and Detroit Lions defensive tackle Alex Karras were suspended indefinitely for wagering on games. The obsession with appearances continued into the new millennium when the NFL famously refused to air a commercial from the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority promoting the city’s tourism and even cancelled a fantasy football convention scheduled to be held at the Venetian casino.

Until recently Roger Goodell, the milquetoast NFL commissioner who has earned more than $500m in salary during an 18-year tenure as a human shield for the billionaire owners he represents, toed the decades-old line and was unequivocal on where pro football stood on the subject even as public attitudes shifted. In 2012, Goodell testified in the NFL’s six-year lawsuit to block then-New Jersey governor Chris Christie’s legalization of sports betting in the state. “I do not think gambling is good for professional sports.” Needless to say, he’s been singing a different song this week.

Related: Super Bowl expected to be biggest sports betting event in US history

The first cracks in the wall came in 2016, when the NHL awarded an expansion team to Bill Foley, the billionaire chairman of Fidelity National Financial, who paid a $500m fee for the Golden Knights. But everything came tumbling down after the 2018 US supreme court ruling that overturned the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act and opened up sports betting around the country – and laid the NFL’s hypocrisy bare. Turns out all those decades of moralizing didn’t have a thing to do with integrity, upholding the public good or “protecting the shield”: the league just wanted their piece of the action.

Like most conservative-leaning cultural leviathans the NFL is slow-moving, which has made the raw speed of its about-face on gambling extraordinary. To no one’s surprise, the NFL announced five-year contracts worth nearly $1bn combined in 2021, with DraftKings, FanDuel and Caesars to become the league’s official sports betting partners, in addition to secondary deals with BetMGM, WynnBET, Fox Bet and PointsBet.

“This stadium is extraordinary and we’re here and we can feel it … and that’s our stage,” Goodell said at Monday’s aggressively moderated state-of-the-league presser, putting a fine point on his employer’s dramatic about-face. “For us the stadium is key, the city is key. This city really knows how to put on big events. We’ve seen that.”

The Raiders finally arrived in 2020, and have thrived in their expensive confines at the bottom of the Strip. The Aces have become the undisputed juggernauts of the WNBA. F1 was a rousing success, following a rocky start, with a deal in place to return for nine more years. Whether it’s the bottomless coffers of Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund or the more than $300bn that’s been generated in the six years of legalized sports betting, the faucet is open for big-time sports.