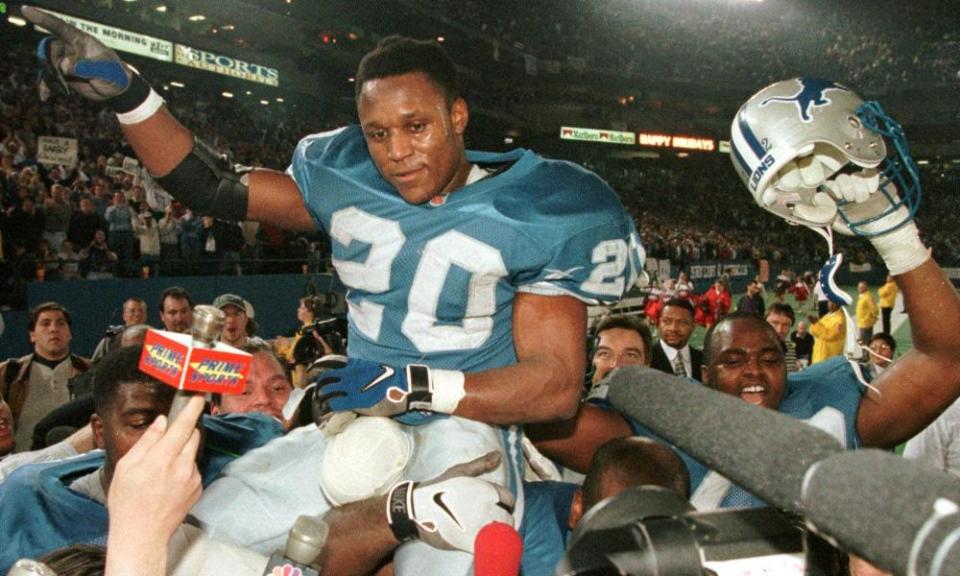

Barry Sanders’s retirement at the top remains an NFL mystery

Barry Sanders’s 1999 NFL retirement still smarts. Jim Brown and Michael Jordan at least pivoted toward new pursuits (acting and, in MJ’s case, baseball for a while) and with their legacies secure. Sanders was 31, ringless and a season or so shy of becoming the NFL’s all-time rushing leader when he spun away to London to escape the press, faxing a goodbye letter to his home town newspaper on the eve of the Detroit Lions’ training camp. “Until yesterday,” one supporter huffed at the time, “OJ was my least favorite runner, but he only stabbed two people in the back.”

It’s taken Detroit hitting rock bottom time and again and other star players walking away from the NFL in their primes – Calvin Johnson, not least – for fans to appreciate Sanders’s lionhearted call. It’s the motivation behind his early retirement that’s long been so mystifying. A new Prime Video documentary called Bye Bye Barry aims for more clarity, but comes up grasping in the end.

Of course there were bound to be challenges in building a film project around Sanders, one of the most understated superstars you’ll ever encounter. He wasn’t so much wary of the media as embarrassed by his celebrity status and keen to drop out of sight any time the spotlight became too intense. “Some things are just unnecessary,” Sanders said after going awol on ESPN after being selected third in the 1989 NFL draft – between Deion Sanders at No 5 and top pick Troy Aikman. “I’m not trying to downplay what you guys do, but you have to respect my judgment and the way I am as a person.”

Since then the 55-year-old Sanders has rounded into a cuddly figure who isn’t quite so serious these days. But Bye Bye doesn’t exactly set him up for the kind of profound introspection that Jordan and Brown showcase in their docs – a real demerit for an NFL Films crew that rarely has to worry about access. (Disclosure: I was a college intern at NFL Films during the 2001 season.) Over the course of the doc’s 90-minute runtime, producers interrogate Sanders under the Fox Theatre lights, fly back to London with him and his sons – but don’t really pull much out of him.

Worse, directors Paul Monusky, Micaela Powers and Angela Torma had a winning playbook in Sanders’s 2003 autobiography Now You See Me – which digs into his regrets, his loneliness and his true feelings about his father, William. “I sometimes wondered if I was ever quite the son he thought I should be,” he writes. “One of the worst moments came shortly before the NFL draft deadline, when Daddy cornered me and cussed me out for even considering staying at Oklahoma State for my senior year.”

Without much in the way of deep introspection from their titular subject, Bye Bye pulls from the familiar NFL Films trick bag of soaring musical numbers, celebrity interviews (Jeff Daniels, Eminem) and archival reels – the star of the show by default. Poetry in motion is a phrase that’s used to exhaustion in sports – but in Sanders’s case, it genuinely applies. Even now he remains like nothing the game has ever seen – a 5ft 8in Houdini with his own knack for moving the chains, an escape artist with a flair for evading would-be tacklers before turning on the jets. (Think Lamar Jackson on his best day against the Cincinnati Bengals – only more unstoppable on the run.) Sanders’s knack for running circles behind the line of scrimmage, legging out 30 yards just to gain three, made him the king of negative carries, too.

Like the genius painter or composer, Sanders was far better at letting the work speak than explaining the strokes. It’s no coincidence that Bye Bye drops the week of Thanksgiving, a football holiday Sanders defined with his ritual carving of my accursed Chicago Bears. (“I hope he doesn’t leave before we can give him the turkey leg,” Fox’s John Madden, Thanksgiving Day host extraordinaire, cracked as the clock ticked down on a three-touchdown masterpiece in 1997 that moved Sanders into second place on the all-time rush list.) In Sanders’s day – when a running back was a team cornerstone, not cannon fodder – he stood head and shoulders above the rest.

At the end of the 1998 season Sanders was just 1,458 yards away from breaking the all-time rushing record – light work for a guy barely a year removed from becoming the third back to rush for more than 2,000 yards in a season. “You see the love for the game in Barry’s eyes, performance and in the way he carries himself off the field,” said Walter Payton, the Bears god who knocked Brown off the NFL’s Mount Rush-More. “Even if you cheered against Barry’s team, you always respected him as a player.”

Looking back, Sanders’s retirement shouldn’t have surprised anyone in light of how often he had refused the spotlight in the past – stopping short of snatching a high school rushing record or stiff-arming the massive attention that descended on him when he claimed the 1988 Heisman trophy at Oklahoma State. “Finally, a guy won the award [based] on just sheer ability,” Aikman said after UCLA’s charm offensive failed to put the quarterback over the top.

“I thought we were gonna compete head to head for many more years,” Cowboys great Emmitt Smith says in one Bye Bye exclusive, recalling the blowout loss Dallas suffered to Detroit in the divisional round of the 1992 playoffs. That Smith wound up surpassing Payton in total rushing yards never quite sat right with folks outside Dallas. Sanders toiled for a decade on some truly putrid Lions teams to produce his numbers, while Smith had five more years and a slew of All-Star teammates to help him. In Bye Bye, even Sanders laments how much further he could’ve gone with a stronger supporting cast – but stops short of subjecting Lions management to another round of withering criticism from his book. As time has passed and emotions have cooled, Sanders’s retirement looks more like the ultimate chess move, with transitory glory sacrificed for his longer term wellbeing.

As to the question, What was Sanders thinking?, the film is happy to leave the job of shedding light on that matter to longtime blockers Kevin Glover, Lomas Brown, Herman Moore and legendary Lions coach Wayne Fontes. In their telling, it was seeing them and other key teammates leave for greener pastures and two more Lions stretchered into disability retirement that affected Sanders most. (The astroturf field inside the dearly decaying Pontiac Silverdome should have been justification enough for him to call time.) But I suspect Sanders also felt queasy about the prospect of topping Payton the very same year Payton announced an irreversible bile duct cancer condition – which killed him three months after Sanders’s retirement announcement. If only someone had sounded out Sanders about all this in the doc, especially now that he’s not ducking anyone any more.

Bye Bye is of a piece with a larger NFL strategy to extend its TV domination to the streaming world and hook the many younger viewers there – ironic, given that NFL Films practically invented the behind-the-scenes sports doc. But to stand out in a new era where documentaries are crafted to be as engrossing as scripted dramas, well, it’s going to take more than the typical effort that hooked the NFL diehards watching on ESPN Classic. This doc doesn’t just play like a facsimile of one of those old PR jobs – the last thing Sanders would want for himself. The whole production feels a bit rushed and reheated.

Sanders has never been a more ripe target for the hard questions that have followed in the wake of his sudden retirement. It’s too bad Bye Bye lets Houdini slip away again under the same old shroud.

Bye Bye Barry is available to stream now on Prime Video.