Brawls, boos and ‘plastic Paddys’: how the English and Irish football teams became eternally entwined

For some around the Irish squad, it's still strange to be preparing for a match against Lee Carsley’s England. Ireland made a strong push for the admired coach, since he has 40 caps for the country. A solid Ireland midfielder is now the most important figure in English football culture, and will have a tricolour by his name if he takes England to the World Cup.

Carsley was born in Birmingham but qualified for Ireland through his Cork grandmother, and spoke last week of naturally feeling both nationalities. The same applies to many for Saturday’s game in Dublin, most notably Declan Rice and Jack Grealish, who make up at least nine England regulars over the last half-decade that could have also represented Ireland. It is almost an inevitable inversion of the fixture’s history, when it was Ireland that most benefited from the country’s diaspora to Britain.

That history has been driven by one of the most complicated relationships in international football – at least on the Irish side. Among those complications are “800 years” of British occupation; a century of post-colonialism; decades of the English top flight serving as one of Ireland’s primary cultural influences as well as hundreds of players. One line frequently uttered in Irish academia is that “England is a huge part of Irish history but Ireland a tiny part of English history”. That is perfectly illustrated by football.

For England, Ireland don’t really register, other than an occasionally romantic story at tournaments. For Ireland, England are the football culture they constantly cast themselves against. Before their opening meeting at Euro 88, Irish physio Mick Byrne turned to fans and growled: “We’ll do them for yiz today!”

There was a lot wrapped up in that line, and the game. The eventual 1-0 victory over England has gone down as one of the greatest moments in Irish history, a nation-building celebration for a young independent country. Ireland were finally on the international stage, and it came against the country that framed their international outlook.

Many Irish players were irritated at the “arrogance” of the English media before that 1988 game, particularly comments about how Ireland were only there to make up the numbers, and references to their “English” players. Midfielder Liam Brady made his displeasure known on ITV, taking issue with Brian Moore’s remarks about the background of some individuals, and Brian Clough’s about their quality.

After the game – and Ray Houghton’s winner – there was only joy.

That it was masterminded by the late, great Jack Charlton only added depth and reflected how intertwined the two national teams had become.

Ireland’s greatest football figure is English. So many of Ireland’s greatest players were part Irish, part English. The same is now true of many of the current English side.

Anthony Gordon and Harry Maguire are of Irish descent, which the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs calculates to apply to 25 per cent of the English population. Ten per cent of the population are eligible for an Irish passport – and thereby the national team – through at least one grandparent. That applies to all of Carsley, Rice and Grealish as well as Harry Kane, Conor Gallagher and Jude Bellingham in the current set-up. This is down to some of the most open citizenship laws in the world, which were set to recognise the diaspora.

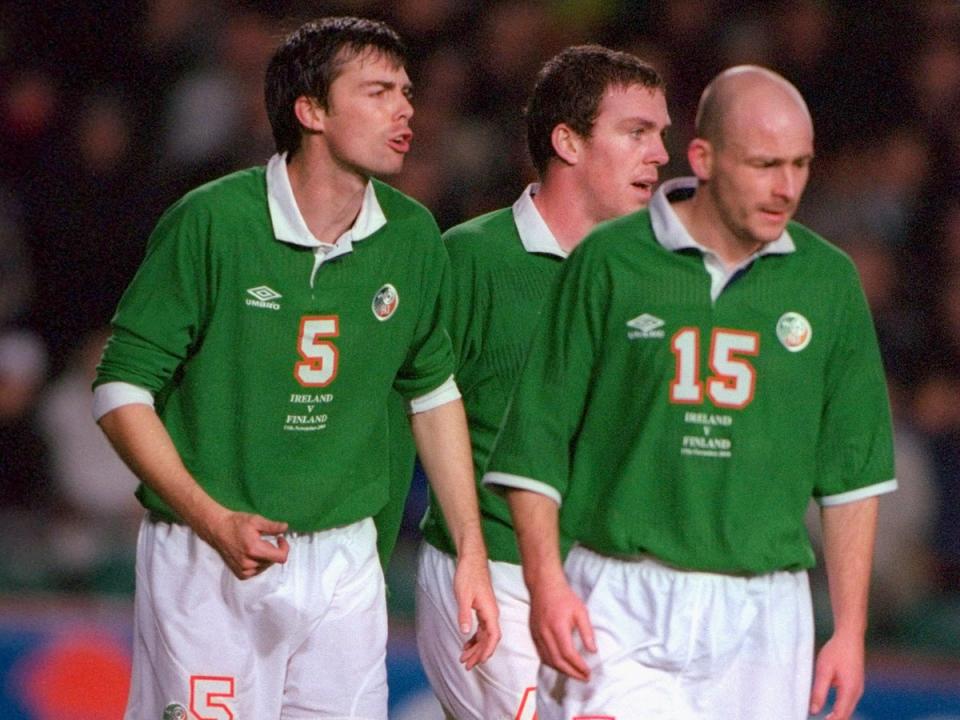

Charlton was the first to seek to exploit this, pragmatically searching for any serviceable player with Irish connections. This raised the notorious “plastic Paddy” claim that was so prevalent around the 1990s, and always provoked a reaction in children of the diaspora like centre-back Gary Breen. Breen was born in London and spent his career in English football, playing for Coventry, Sunderland and Wolves.

“For me, despite my accent, it’s never been a decision,” Breen told The Independent. “I’ve always considered myself Irish. I’ve got no English relatives. I was brought up in Camden Town in the Seventies and Eighties, where there were probably more Irish people than in some of the counties in Ireland. Holidays in Ireland, Irish music...”

While Breen’s words illustrate there was always some consciousness about accents – and the many English accents in Irish squads – he says the squad was more attuned to “feeling”. All that ultimately mattered was buying into the spirit.

The wider point here is that there are significant shades of grey rather than green and white. Rice and Grealish are the next generation on from players like Breen, where the sense of Irishness is naturally more diluted.

“My background is very different to Declan, which is one grandmother,” Breen says. The feeling is stronger for many of the next generation’s parents. Harry Kane’s father, Pat, like Breen, is known to frequent the long-established Gaelic games pubs around north London. Such Irish experiences form happy conversations among many English players’ families at tournaments, particularly with the Grealishes.

It all adds up to seven English-eligible Irish players against five Irish-eligible English players for Saturday. That is certainly a shift from Euro 88 when it was 10 against two.

By the same token, this is almost a new generation of England-Ireland fixture. You can trace the relationship through the games.

The 1991 European Championships qualifier at Wembley, a rare period when Ireland were the superior side, came at a volatile time of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Paddy Hill, one of the Birmingham Six wrongly convicted for an IRA bombing, attended the game just two weeks after his release. Chants of “No Surrender” punctuated the night. Charlton, who was at Wembley for his only away match against England as Ireland manager, was called “Judas”. He angrily told his players: “I won the World Cup for this country.”

Most infamously, the 1995 Lansdowne Road friendly had to be abandoned after rioting by England fans, five minutes after the home side had taken the lead. Irish supporters constantly cast themselves against that aggression, taking pride in good behaviour.

That match led to a long hiatus between meetings, a period that witnessed an economic boom in Ireland. Rather than going to London looking for any work at all, Irish people migrated for high-powered careers. The only interaction with England on the international stage, meanwhile, was watching them in tournaments as a gap grew between the squads. In a reflection of Ireland’s new self-confidence, though, these summers raised public debates over whether the country was now “mature” enough to support England. Many said no, pointing to “arrogance”, history or just feeling.

A common counterpoint to all this was that those same Irish people have absolutely no problem supporting Premier League clubs as if it’s their own competition.

It’s commonly said in Ireland that you can guess a person’s age by who they support. While Manchester United and Liverpool are constants, Leeds United illustrated a child of the 1970s through John Giles, Aston Villa the 1990s through Paul McGrath.

This has long aggravated some in the League of Ireland, especially given the effect on revenue and development. It’s also changing. Brexit and the Premier League’s evolution into a truly international league have meant fewer opportunities for Irish players by virtue of a rising threshold. That has provoked debate in Ireland over whether the national team should even need diaspora talents like Grealish and Rice.

A big question ahead of Saturday’s Nations League opener, as the duo face an Irish crowd for the first time, is whether they’ll be booed.

It would be nice to think it would just be pantomime or that too much time has passed, but that points to another oddity. Saturday is just the 18th meeting between the two countries and only the fifth in 34 years.

Given the depth of connections, that’s almost as strange a fact for supporters as England being managed by an Irish international.