How Craig James went from the voice of college football to TV pariah to seminary graduate

DALLAS – Craig James’ square jaw, perfectly coiffed hair and All-American charisma helped make him one of the most recognizable faces of college football for nearly two decades. From ESPN analyst Lee Corso nicknaming him “Mustang Breath” in the early days of ESPN “College GameDay” to a long analyst stint on ESPN’s “Thursday Night Football” package, James was intertwined with many of the sport’s biggest moments.

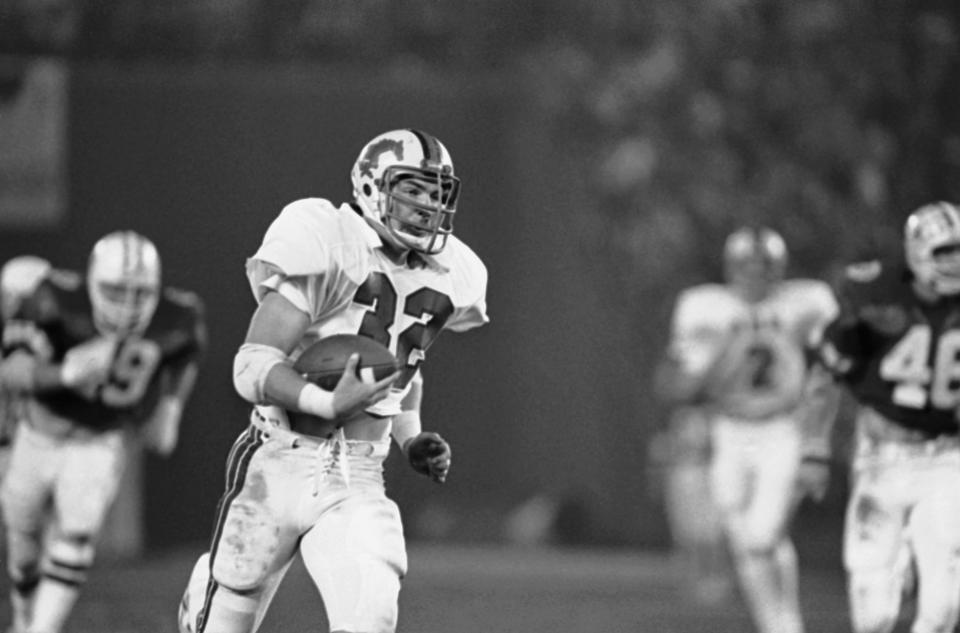

After compiling impeccable playing credentials starring at tailback at SMU and for the New England Patriots in the NFL, James made $416,000 for his work at ESPN as recently as 2011. James became such an entrenched part of the media scene that he started the “Craig James School of Broadcasting” in 1993 to train former coaches and players.

“He was Herbie before Herbie,” said James’ old ESPN colleague, NBC’s Mike Tirico, referencing beloved ESPN analyst Kirk Herbstreit.

These days, the most notable part of James’ broadcast repertory is his complete absence from the airwaves. James’ last television gig came in August 2013, a one-episode stint on an obscure Fox Sports Southwest show that ended in a controversial firing. As his prominence has faded from both screen and memory, a complicated question looms: Whatever happened to Craig James?

A breadcrumb trail of legal documents, polarizing political statements and high-profile controversies have left him virtually unemployable in the modern broadcast climate.

Inquiries to he, various lawyers and affiliated political organizations culminated with a text message from James to Yahoo Sports this week: “In 2014 my commitment to the Lord and my family took center stage in my life,” adding that he recently graduated from the Dallas Theological Seminary. “Life is good being a Monday morning armchair [quarterback],” he said. “To God be the glory.”

The unraveling of James’ television career from the sport’s leading analyst to armchair quarterback weaves through a series of controversies that includes his role in Mike Leach’s firing at Texas Tech in 2009 and a doomed Senate run in 2012. James received just 4 percent of the vote in losing to an upstart Republican candidate, Ted Cruz, in the primary.

“It was one of the most bizarre and ill-fated campaigns we’ve seen from someone of prominence in the state of Texas,” said Mark Jones, a professor of political science at Rice University.

James’ candidacy was doomed by both his complete lack of political experience and his emergence as a lightning rod in the state for his role in Leach’s firing after allegations of mistreatment of James’ son. James’ political strategy may have cost him any return to television, as Jones recalls James taking a stance to the right of the notably conservative Cruz.

During that campaign, James, 57, made a flurry of inflammatory statements, including that gays “would have to answer to the Lord for their actions” and that being gay is “a choice.” He criticized an opponent for taking part in a gay parade: “Right now in this country, our moral fiber is sliding down a slope that is going to be hard to stop if we don’t stand up with leaders who don’t go ride in gay parades.”

In explaining James’ dismissal after one show on Fox Sports Southwest, a Fox spokesman initially nodded to these comments in a statement to the Dallas Morning News – “he couldn’t say those things here.”

James filed a lawsuit against Fox for religious discrimination, backed by the Texas-based Liberty Institute, and he also joined the Washington-based Family Research Council, which claims to advance public policy from a “Christian worldview.” The lawsuit, which was announced with fanfare, led to Fox responding with a 224-page motion to dismiss, much of which doubles as a troll over James’ journalistic shortcomings during the Leach saga. A letter in the court filing serves as a description for why James’ ostracization from mainstream television likely won’t end. It sums up James, a former face of the sport, as “divisive, contentious and undesirable.”

Back when Herbstreit played quarterback at Ohio State, he can remember sitting in the Buckeyes’ team hotel in September 1992. As they killed the day waiting to play No. 8 Syracuse, Herbstreit watched ESPN with rapt attention.

The Buckeyes had struggled in early season wins over Louisville and Bowling Green, and Herbstreit recalls James comparing the Orange to a Corvette and the Buckeyes to a clunky truck. More than a quarter century later, he still remembers James’ specific caustic comments about Ohio State.

“Craig James was as obnoxious as he could be about how Ohio State was from the Big Ten and slow and in for a rude awakening,” Herbstreit said. “You talk about galvanizing. You should have seen our locker room. What was missing for two weeks was there and we blew them out.”

Herbstreit recalled the anecdote in a recent phone interview not to pick on James. He was illustrating just how powerful James’ voice was at a time when there simply weren’t that many voices in the sport.

“You have to take your readers to the era,” he said. “No ESPN News or SEC or Pac-12 Network. There was just one show … and people tuned in to watch Craig be the sarcastic and cocky guy.”

A few years later, Herbstreit recalls being at a pay phone in the Detroit airport on his way to call an Arena League football game. He’d auditioned for James’ role on “ESPN GameDay” after James left for CBS to be a fixture of their NFL coverage. Herbstreit never dreamed he’d get it, as he’d only been doing local media and the occasional Kurt Warner arena game. Herbstreit took a knee in shock when his agent told him he’d got the job. He knew it would change his life forever.

Herbstreit says being just 26 at the time was a blessing, and he recalled the prospect of replacing a voice as prominent as James as “terrifying.”

“He was the guy, and it left a gaping hole on their desk,” Herbstreit said. “Craig was the hot guy at the time, he’d played with the Patriots in the NFL. But it wasn’t just his NFL background, he had a charisma on-air and a swagger that he brought.”

The turning point in Craig James’ transformation from media mainstay to exiled outsider can be traced to the contentious events of December 2009. James’ son, Adam, suffered a concussion in bowl practices for Texas Tech. The handling of that led to the firing of Mike Leach, lives indelibly altered and it took more than five years to litigate in the courts.

The version of the story pushed by the James family involved Leach punishing him by banishing him to a small dark closet. Leach denies this version, as he wanted Adam James away from the practice field and out of the sunlight to deal with the concussion.

Emails that emerged later showed Craig James used a Texas-based strategic consulting firm, Spaeth Communications, to leak information to publicly pile on Leach. That included a video played on ESPN’s “SportsCenter” that Adam James took from his alleged exile. Leach later said, “ESPN … was just spewing this stuff that Spaeth and Craig James were feeding them.” As emails and phone messages emerged in the legal process, Craig James came off as an overbearing Little League dad who’d leave coaches lengthy messages complaining about his son’s playing time. In Fox’s 2015 legal filings to get James’ lawsuit dismissed, they claimed: “Leach’s dismissal left many viewers with strong, negative opinions about James’ credibility and journalistic ethics.” (That suit got settled and attorneys agreed to dismiss it in 2016.)

Leach’s lawsuit against ESPN, James and Spaeth was filed in 2010 and took until 2015 to finally cycle out of court. Leach lost his final appeal to the Texas Supreme Court. By then, Leach was back coaching at Washington State after sitting out the 2010 and ’11 seasons. James didn’t return requests seeking specific comment. Adam James, according to LinkedIn, appears to work in real estate and land development in the Dallas area.

Leach remains bitter about the firing from Tech and James’ role in it, because he feels it cost him his job at Tech and two prime years of his career. In a recent phone interview, Leach said of James: “You create your own karma. It looks like he might have created his. I think he’s a dishonest person and the sport is better off without him. And that’s pretty clear-cut.”

According to Texas Monthly, James described his battle with Leach during a speech at a church as a “spiritual war.” He illuminated that comment by telling Texas Monthly in 2012, “There’s a lot of people who don’t have a faith and don’t believe what I believe, who want to rip me up. They don’t like the fact that I go home to the same lady every night and have for 29 years.”

Even those who remain more aligned with James question his decision to run for political office. Former Texas Tech chancellor Kent Hance, who considers James a friend, advised him against running for Senate. Hance, who is a former U.S. congressman, summed up James’ fall this way: “He understood football and announcing, but he had no conception of politics. Especially going for U.S. Senate on your first try. It’s like being an engineer and all of a sudden trying to be a banker.”

SMU coach Sonny Dykes saw James’ legal battle from both sides. He worked for Leach, considers him a friend and spent hours on the phone with him talking about James. Dykes also recruited Adam James to Texas Tech as an assistant and coaches on the campus where Craig James rushed for 3,742 yards as part of the iconic Pony Express with Eric Dickerson. (James admitted to the Dallas Morning News during his political campaign that he took “insignificant” extra benefits from boosters, as he was there during a corrupt era that led to the school receiving the NCAA’s dreaded death penalty.)

Dykes said he wishes James would come around SMU more, yet understands why he’s a controversial figure.

“You know, he kind of messed with the wrong guy,” Dykes said. “Mike Leach has a lot of people that like him and some powerful people. It seemed like that got the tide turned against Craig. I don’t know what happened. I really don’t.”

One of the hallmarks of James’ disappearance has been a distinct lack of nostalgia or clamor for his voice to return to the scene. He’s done occasional media appearances the past few years: He tweeted about a recent spot on the “Tony Bruno Show” and did an interview earlier this year for a book on Texas high school football.

James tried to engage his old contact base for his podcast – “Airing It Out with Craig James” – which ended in January 2016 after 45 episodes. A website that promoted that podcast and some of James’ writing – CraigJames.com – appears to have stopped being updated around the same time. James mixed football analysis with religious writing. Articles included, “Of Course, Evangelicals CAN vote for Trump,” “Transgendered Insanity Sweeps the Nation” and “The Dangerous Truth About Atheism.”

Financially, James doesn’t appear to need the work, according to media reports that emerged during his campaign. He sold part of a business for $3 million before his campaign and owns an annuity that’s slated to pay him at least $500,000 a year. He owns a ranch worth at least a half-million dollars and is selling his gated ranch home in Celina, Texas, for nearly $1.5 million. It rests hundreds of yards behind a gate, with an American flag towering over the entrance.

James says he’s comfortable in his role outside the media. He has a certificate in Biblical and Theological Studies from Dallas Theological Seminary. James said he’s found a new role. “As a modern day warrior for Jesus Christ, I seek to share His Good News for all,” he told Yahoo Sports in a text.

His ties to the television industry have loosened the past few years. James had the paradoxical existence of being well known without being beloved, famous without being popular and friendly yet distant to many who worked with him. A Big 12 source summed him up this way: “He had a unique way of covering up ignorance with arrogance.”

Tirico considers James, who he endearingly calls “Pony,” a “lifelong pal” after their years together at ESPN. Tirico hadn’t seen him in years and ran into him at a Patriots game two years ago and they reconnected like they’d spoken last week. But Tirico understood the media exile and difficulty James will have returning from it. “When you go down the road as staunchly as he did,” Tirico said, “it’s hard to cycle back and be the All-American running back.”

James told Yahoo Sports he’s “attended all six of my grandkids’ births!” He added that his nickname has changed from “The Pony” to “Pop C” to his grandkids.

In the wake of negative headlines from the Leach drama and the untrue claims about James killing prostitutes that still exist in his Google profile, James theorized to Texas Monthly that there’s “a group of people who would like to see me come down.” He added: “They don’t like that I’ve been a dad and I’ve been there for my kids. They don’t like that I’ve been in the spotlight but haven’t stumbled.”

More from Yahoo Sports:

• Ex-MLB star makes absurd offer to President Trump

• Heisman winner Kyler Murray has tough choice to make

• College hoops player sued over sex tapes

• Dana White on Oscar De La Hoya: ‘He’s a liar and a phony’