How England can bring out the Saracens version of Owen Farrell at the World Cup

Nobody could have finished watching last month’s Premiership final without believing that Owen Farrell will be a big asset to Steve Borthwick at the upcoming World Cup, where a sympathetic draw gives England the chance to go far into the tournament.

Equally, though, it was natural to wonder how Borthwick will attempt to bring that version of Farrell; intense, accurate, creative and composed. Here are four issues to weigh up.

Time at 10

Perhaps a blindingly obvious place to begin, but Farrell has spent most of his Test career at inside centre. It will be interesting to revisit that upon his retirement. Has it been a bit of a waste or the best way to keep the best players available to England – and the British and Irish Lions, if we think back to 2017 – on the field together?

Only in exceptional circumstances does Farrell shift position for Saracens, who often populate their match-day squads with four other potential centres. At the weekend, for example, they started with Nick Tompkins and Alex Lozowski with Duncan Taylor and the versatile Elliot Daly on the bench. Josh Hallett and Olly Hartley are likely to play more next season.

Moving away from fly-half hampers Farrell for a few reasons. Firstly, his kicking game is mitigated. In the opening exchanges against Sale Sharks, he put Saracens on the front foot immediately with this spiral bomb. Under pressure from Tom Curry, Farrell strikes a kick that swirls into the air and allows Max Malins to challenge Joe Carpenter.

Malins bats the ball backwards, Nick Tompkins collects and Sale must defend their own 22:

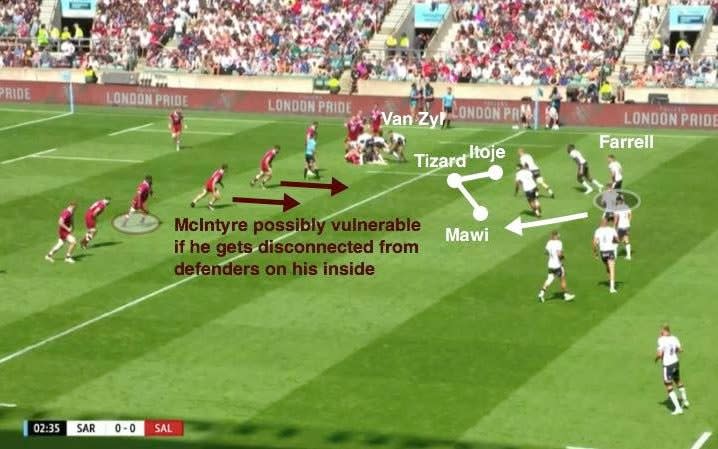

Were he at inside centre, Farrell would have been unlikely to receive the initial pass from Ivan van Zyl. And he would probably not be close enough to organise his forwards on this phase a few moments later. Look how deep this pod of three is, allowing them to build up speed. Farrell is nestled behind, and eyes Simon McIntyre in Sale’s defensive line:

Remember his break against Northampton in the Premiership semi-final?

Farrell threatens something similar by accelerating onto Hugh Tizard’s shoulder before curving away as his team-mate takes contact:

The integrity of Saracens’ shape, coming from deep and posing multiple dangers to Sale, is what creates quick ball as much as the power of the carry. Farrell is partly responsible for that.

On the next phase, McIntyre is still there to be targeted. Farrell has Ben Earl, Jamie George and Nick Isiekwe to his left and Tompkins to his right:

He pushes flat, steps to the inside of McIntyre and fixes Curry before flicking a pass to Tompkins. Sale do well to recover as Earl floods through:

Offloading remains an underrated aspect of Farrell’s arsenal. While he will often stand at first-receiver when wearing 12, laying at fly-half often forces him to push flatter, giving him more scope to use it. Secondly, he seems happier and more influential when defending at fly-half. Farrell’s strip on Manu Tuilagi set the tone for a fine tackling display.

Over the course of the past year or so, following the lead of France at Twickenham in 2021, international teams targeted the England midfield from first-phase moves. Argentina scored last November with a clever wrap-around that outflanked a centre partnership of Farrell and Tuilagi. Months later, Scotland dangled Finn Russell as bait to tempt Farrell out of the system.

A balanced backline with ball-players and ballast

While it would benefit any fly-half, a balanced backline selection has not always appeared to be an overriding priority for England.

Cohesion certainly helps, but the Saracens backline functions so well because of how the individual parts complement one another. Alex Goode, Daly and Max Malins are intuitive playmakers that ease pressure on Farrell.

Goode stepped up at first-receiver from this scrum against Sale, following Earl’s burst, and grubbered ahead for Saracens’ penalty try:

Goode’s deft clip, finding space in the Sale back-field and allowing Duncan Taylor to close down Carpenter, brought about Daly’s try:

Van Zyl’s crucial – and somewhat controversial – finish was instigated by a clever set move in which Farrell did not even touch the ball.

It is a variation on the popular ‘slide’ play, with Tompkins standing at first-receiver. This move has plenty of different options, with the vast majority moving the ball in the same direction as the fly-half arcing out the back. Usually, the blindside wing would be travelling in that same direction.

Here, though, Malins sets up on the inside of Tompkins. Curry cannot plug the gap to George Ford’s left…

…and a try results:

Tompkins and Alex Lozowski have formed a tough, rounded centre combination for Saracens. Van Zyl is a sparky scrum-half with a sniping threat that helps out Farrell, and another huge part of Saracens’ success this season.

England cannot pick Van Zyl or Tompkins and are unlikely to turn to Goode. Unless they recall Lozowski, a midfield of Dan Kelly and Ollie Lawrence, the latter in his favoured role of outside centre, might be worth a shot. Though inexperienced, Kelly has promise as a flinty, skilful all-round operator.

As for the auxiliary ball-players, this is tricky. While he possesses extremely valuable qualities, Freddie Steward is not an assertive distributing full-back like Goode. That could tempt Steve Borthwick into picking one of Malins or Daly on a wing. Could Malins even usurp Steward at full-back?

The scorching irony is that the eagerness for multiple playmakers is what has moved Farrell away from fly-half and into partnership with Ford and Marcus Smith. Whether or not one of those combinations is used, even as an option within a game, kick-pressure alone will not take England to the late stages of the World Cup. Against stronger Test defences, they will have to move the ball and take try-scoring chances.

Direction and attitude

Mark McCall has continually stressed that Saracens altered their outlook rather than their style and Richard Wigglesworth must inject a sense of urgency when he arrives to coordinate Borthwick’s attack for World Cup pre-season.

On club duty, Farrell is part of a side that has licence to go for broke on turnover ball and to go wide when inside their own 22 if space presents itself. It seemed telling that Martin Gleeson, the former England attack coach, described Farrell as “definitely not conservative, unless it is put it on him to be”.

England’s players have been told to turn up to their training camp in good shape, because fitness cannot be the sole focus. They have a couple of months to sharpen their skills and make themselves into an effective attacking outfit. Saracens have shown what is possible if you have greater conviction.

Strong line-out work

One fallacy surrounding Farrell is that he can only excel at fly-half with a dominant pack. Saracens had to navigate the end of their season without Billy Vunipola, Andy Christie and Theo McFarland. Sale were also missing Ben Curry and Dan du Preez, yet were hardly dwarfed up front at the weekend. Indeed, the superiority of their scrum kept them in the contest. In Tuilagi and Jean-Luc du Preez, they had two of the most muscular carriers on the pitch.

However, on both sides of the ball, Saracens line-out shaped the game. Maro Itoje ran a slick operation, with Theo Dan replacing Jamie George and producing a fine performance. Steals on the Sale throw, from Isiekwe and Itoje, stunted Sale at vital moments.

An imposing and disruptive defensive line-out is particularly handy when you have a fly-half capable of pinning back opponents. This strike from Farrell did not count as a 50:22 because the ball had been passed back into the Saracens half…

…yet it forced Sale into an awkward position, from which they had to clear and surrender an attacking platform.

Borthwick is a line-out guru who has enlisted the help of George Kruis. As he knows, when a team can connect different facets of their game, they will bring out the best in their fly-half. England and Farrell are no different.

Match images from Premiership Rugby