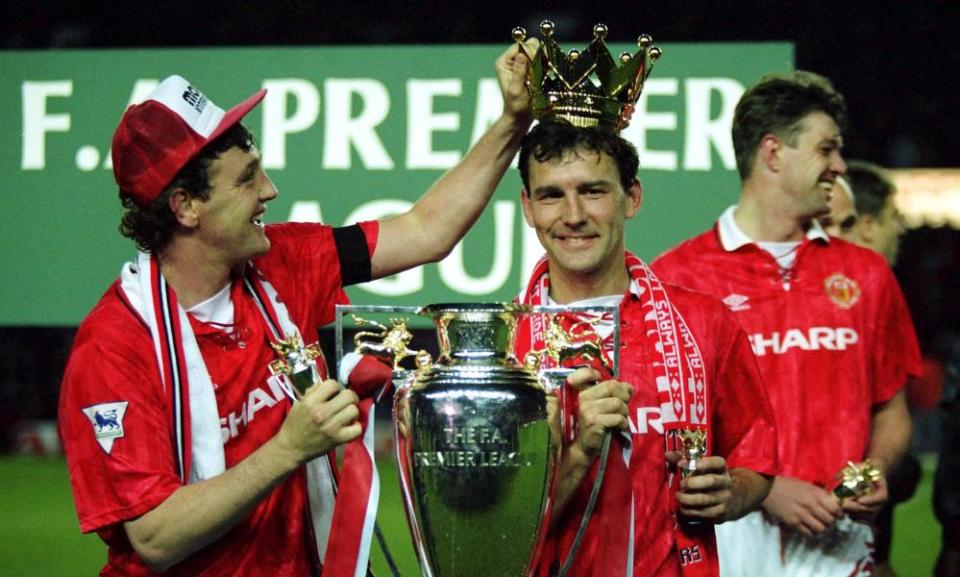

Golden Goal: Bryan Robson for Manchester United v Wimbledon (1993)

Very little gets people as excited as football, a fairly embarrassing admission to make given 200,000 years of human history: a bunch of people kick a ball about, then the rest of us go on like it’s something we’ve done ourselves. Except in a way it is, because our clubs were built by us and form part of us, representing where we’re at and what we believe in. So inasmuch as anything makes sense the extent of our love for them makes sense, and when we talk about football what we’re really talking about is love – love for who we are.

Related: Golden Goal: Ronaldinho for Barcelona v Chelsea (2005) | Daniel Harris

I fell for myself in the traditional way: my grandad had a season ticket at Old Trafford in the 40s and 50s so gave the gift of United to my dad, who gave it to me. As such, tales of the Busby Babes were inculcated with the same fervency and pride as those of the various bible lads, all mine and all part of my family history. Happily, the zestful, disputatious sensibility that links Judaism and the Red Devils chimed with my natural inclination, but ultimately the miracles of Best, Law and Charlton proved more compelling than revelation at Sinai – no offence, God old mate. If it’s any consolation, you lost to worthy opponents.

The United of my childhood were personified by Bryan Robson, a selfless, self-sabotaging, inspirational and inarticulate leader in the grand Jewish tradition. My first footballing memory is my parents going to the 1983 FA Cup final replay, leaving four-year-old me at home – a decision they regretted and I still regret. I remember being staggered that, with United 3-0 up and Robbo on a hat-trick, he declined to take a penalty he won; soon after, I expressed disappointment that I’d been called Daniel not Bryan, and mastered his signature before even attempting my own.

United’s obsession, though, was with the title, which they’d been without since 1967. They were in the hunt the next April – and for the Cup Winners’ Cup too, having eliminated Barcelona thanks largely to Robson, who scored twice while dominating Diego Maradona in a performance of disquieting superhumanity. Problem being he then got injured, chances of success disappearing with him.

The following year United won the cup again and again Robson was colossal, scoring the goal of his life in the semi-final replay against Liverpool. The accordant vibe fired the team to 10 straight wins at the start of the next campaign which made them certain champions ... until Robson got injured, missing nearly four months before returning for a crucial game away to West Ham. Typically, he scored the opening goal … then got injured, and United lost to help Liverpool to win the league, a decade – my childhood – in a day.

Before long, Alex Ferguson was installed as manager – to negligible effect! – so my dad continued regaling me with all he’d seen, which necessarily denigrated all I was seeing. I could not get enough.

Robson, meanwhile, remained improbably boyish and impeccably handsome modelling every kit I was bought and every piece of leisurewear I was denied. It wasn’t until much later that I realised his knowing, lightly curled smile described sessions of astounding length, breadth and depth, but it was mesmeric nonetheless so when I got a hamster, naturally I called him Robbo. Unsurprisingly, he didn’t last long and was soon replaced by the equally heroic but more physically robust Sparky.

Related: Golden goal: Keith Houchen for Coventry City v Tottenham (1987) | Daniel Harris

Gradually, my understanding of the game developed beyond seeing Robbo as my footballing dad – if he was there I was safe and if he wasn’t I wasn’t – but his peak came before I attained full footballing consciousness. So, though I have clear memories of Euro 88, at which he played the Netherlands of Koeman, Rijkaard, Gullit and Van Basten on his own and kept it level for 70 minutes, I don’t have the perfect handle on his brilliance. But I have an unimpeachable handle on that of Roy Keane and know no one older who rates him higher – the highest compliment imaginable.

Like Keane, Robson was a midfielder without prefix, simply playing in the middle of the field – and down the sides, and in the corners, and at each end. Consequently, his magnificence had to be experienced and cannot be condensed – he wasn’t the highlights, he was all of the lights (all of the lights). Hilariously hard and horrifyingly committed, he combined positive passing with a poacher’s proclivity, bang at it in every game and every training session to the uniform reverence of those he played with, against and for.

But he still hadn’t won the league, and increasingly that was my fault because, though ownership of a club is forever shared, responsibility for its behaviour gradually moves from parent to child. Whether that represents informal correction or simple inheritance is unclear, but references to them inevitably feature the damning, accusatory phrase “Your team”. Unless they win.

Which they suddenly started to do – led, of course, by Robbo, who in 1990 returned from yet another injury to score in his third straight FA Cup semi. I actually missed that goal as, buzzing off Crystal Palace’s earlier win over Liverpool, I curled a perfect free-kick into the top corner … of my bedroom window, from the inside. It was well into the second half before I was invited back downstairs.

A month later, Robbo became the first captain to lift the trophy three times then got injured at the World Cup; it is not too much to say that with him, England would have beaten West Germany, just as it is not too much to say that, had he been fit in 1986, there would still be a Maradona-shaped hole in the Azteca turf. He did, though, win the next season’s Cup Winners’ Cup, another telling performance guiding United past Barcelona in the final.

But with time running out, the biggest prize still eluded him. It looked likely the following year, until a run of two wins, two losses and four draws – including a 0-0 with Wimbledon on my barmitzvah – ruined everything. Robson missed seven of those games, returning for the most humiliating humiliation of them all: a defeat at Liverpool which handed the title to Leeds. I wasn’t there to hear the Kop sing “You’ll never win the league,” but accounts of the toll that exacted on hard, grizzled men are harrowing enough.

Robbo spent most of the next season injured, losing both his number 7 shirt and his public to Eric Cantona. Though he contributed on his return, coming off the bench to pass, foul and advise the referee, the team no longer belonged to him … but the title was on.

Episode 9 is here! Daniel and @AndyBurnhamGM discuss Eric Cantona, the horror of burgling Duncan Ferguson and how on earth you can want to be Prime Ministers. Oh yeah, and the 1995 FA Cup final. https://t.co/wWaLL7f0b8

— United Rewind (@unitedrewind) April 8, 2021

Midway through April, United travelled to Crystal Palace, and with Aston Villa losing at Blackburn knew that a win would take them four points clear with two games left. Ordinarily, I’d have been at Selhurst that night, but my dad was away so there was no one to take me, and when they eventually scored, twice, I missed the aforementioned hard, grizzled men losing their minds with emotion.

By the time they played next the wait was over, and in the final minute of their final home game, they won a free-kick just outside the box. As the only first-teamer who hadn’t contributed a goal, Gary Pallister was summoned to take it, and sure enough, in it went. Robbo hadn’t either but he no longer counted, and though he did get to lift the trophy alongside Steve Bruce, it wasn’t quite his simcha. He was the rabbi, not the chossen.

The final game of the season was Wimbledon away, and this time we were there to watch Robbo, back in the team for sentimental reasons, lead out the champions. I was 14 then and attended the school at which my dad was deputy head, which is to say yes, I did shame him by making sport of his colleagues on a daily. Consequently, things at home were frequently fraught – I’m an only child, so my parents had neither distractions nor compensations – and United was the one thing my dad and I could enjoy free of the tension which affected all the other stuff we had in common, such as our entire lives.

I remember little about the game because the only thing that mattered was the party taking place in all four stands, but then, on 70 minutes, Steve Bruce clipped a hopeful ball over the top … and somehow, Robbo was alone in 40 yards of space! If you go the game, you know about the clutch – that moment when your team should score, so you and the person next to you – often a stranger – take hold of each other, braced for the explosion of ecstasy that nothing can replicate, not even actual ecstasy. But this was something more; the clutch was with my daddy, and on the line was a not just a hero completing his life’s work in front of us but a moment that would nourish us until we’re both dead.

So Robbo watched the ball out of the air, time simultaneously freezing and speeding, took a cushioning touch as it landed, then another, then another … steadied himself … and slotted inside the near post! There was bedlam in the stands, but it was nothing compared to the bedlam in my heart, my dad and I cavorting together in celebration of everything – even, in a strange way, my impending suspension for setting the science lab floor alight. Sure, this was Robbo’s moment, a hero completing his life’s work right there in front of us, but it was also our moment and, if I’m being real, my moment. “My team”, part of me in a slightly different way to they way they were part of all the other people they were part of, had ended my childhood with the greatest moment I’d ever known, a joyous intensity fusing everything I’d been into everything I could be, the possibilities infinite and my world making perfect sense. That’s what we’re talking about when we talk about football.