‘The greatest theatre in sport’: Why players love the haka

Not too many aspects of rugby union puncture the public consciousness, let alone become instantly recognisable.

Antoine Dupont, the phenomenal France scrum-half, is doing his best by making moments of utter brilliance seem ordinary and should captivate a new audience when his exploits for the sevens side at this summer’s Olympic Games are beamed around the world. But a haka from the All Blacks is different.

“It’s the greatest piece of sporting theatre on the planet,” declares Will Greenwood, the former England centre and Telegraph columnist. “I’m not a thespian. I like a big show. I like Top Gun and Take That. And the haka is unbelievable.”

A ritual that honours the Maori heritage of New Zealand has been associated with the sport since the late 1800s. Over 130 years later, it has sporadically sparked controversy. Some weary critics have accused the All Blacks of overkill or undue aggression, with throat-slitting gestures especially divisive.

Occasionally, curious episodes crop up. Back in 2006, when the Welsh Rugby Union expected them to stage a haka between national anthems rather than prior to kick-off, New Zealand opted to perform in their own changing room to an audience of non-playing squad members and backroom staff. Greenwood remains unequivocal. “You never want to live in the past,” he says. “But, wow, I’d love to face the haka one more time.”

There are definitive milestones in its modern history. Wayne Shelford is credited with reviving the haka in 1987 when it was in danger of dying out. In 2005, the ‘Kapo o Pango’ challenge was introduced as an alternative to the traditional ‘Ka Mate’. A decade later, the All Blacks adopted an arrowhead formation with their captain at the front. Then, at last year’s World Cup, Aaron Smith brandished an ornamental paddle to lead the haka.

Brad Weber, who has just finished his first season with Stade Français in Paris, has represented New Zealand in 19 Tests. Courtesy of his ancestral ties to Ngati Porou tribe – “my grandad was a ginger-haired Maori”, he says – the 33-year-old has also played for the Maori All Blacks nine times. Weber remembers solo renditions of ‘Ka Mate’ in front of the mirror as a kid, suggesting that most Kiwi youngsters will have done the same. He encountered school hakas and regional hakas, but singles out two poignant performances with the Maori All Blacks as particularly special.

“The first against Munster in Limerick,” Weber says. “It was just after Axel [Anthony] Foley had died and it was eerily silent. The other one that was huge was against Ireland in Hamilton a couple of years ago. It was the first since Sean Wainui had passed. I played a lot with Seany boy.

“He was an unapologetically proud Maori man who was incredibly passionate about his roots and preserving Maoridom and Maori culture. He was also really helpful to people who weren’t as aware of customs in the Maori world. I remember a lot of times with the Chiefs, he would help people out with pronunciation and things like that. He was a huge part of our lives.

“Seany embodied what it means to be Maori, in my mind. Doing that for him, with his photo on the big screen behind us and his family standing there as we did it, was pretty incredible.”

Weber’s sentiments relay the spiritual significance of hakas, which are often used to mark tournament victories or events such as the retirement of a respected senior player. Students from St Patrick’s College in Wellington produced a stirring version at the funeral of Jerry Collins in 2015. Just this weekend in Tokyo, the Maori All Blacks and Japan marked Connor Garden-Bachop’s death before the visitors’ haka.

One wonders whether the novelty wears off. It certainly seemed that way for David Campese, the iconic Wallabies wing, who ignored the haka and wandered off to warm up on his own at the 1991 World Cup. In fairness, that was Campese’s 21st Test match against New Zealand. “If you’re an England player and you’re lucky enough to play against the All Blacks five times, that’s a good career,” Greenwood adds. “You don’t want to waste a single second of what’s happening in front of you.”

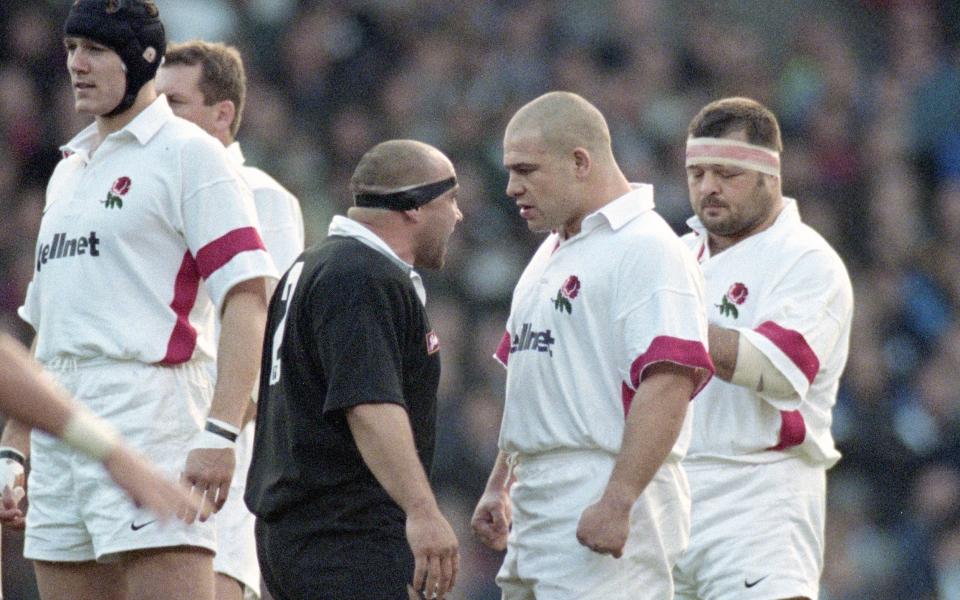

Greenwood earned his second cap, and took on the All Blacks for the first time, on the day in 1997 that Richard Cockerill stood nose-to-nose with Norm Hewitt. He was opposite a backline comprising Justin Marshall, Andrew Mehrtens, Jonah Lomu, Alama Ieremia, Frank Bunce, Jeff Wilson and Christian Cullen. “I should have been s------ myself, because I was 10st wet through,” Greenwood continues. “And yet, I couldn’t help but smile.”

Patient enough to answer the basic questions of a layman, Weber explains that the prestige does not dim with lesser games. “I can see how you might think that, but for a home game, it’s huge. The crowd loves it, they froth it. You get so much energy knowing that you are doing it for them,” he says.

“Then, in away games, it’s huge. The ground and the dirt are quite significant spiritual things for Māori, because that’s how you connect with your ancestors. The stomping on the ground is you channelling those who have gone before you. When you’re way away from home on the other side of the world, it’s your way of connecting. That’s what I thought of in those moments.”

As far as logistics, senior All Blacks will choose which haka will be used before relaying that to the squad for a practice. For a Saturday game, that will mean practice on Thursday evening and a rehearsal at the captain’s run the following day. ‘Kapo o Pango’ was seemingly reserved for grudge matches or high-stakes games, with Aaron Smith once revealing that the All Blacks would usually pick ‘Ka Mate’ if there was a debutant in the side.

Interestingly, since a ‘Ka Mate’ ahead of the 25-25 draw with England in November 2022, New Zealand have performed ‘Kapo o Pango’ in 11 of their last 12 Tests. Home or away, the crowd tends to react as players sink to one knee at the start of the intense routine that was ushered in by Tana Umaga and co in 2005. Across 2023, only the 96-17 thrashing of Italy was foreshadowed by ‘Ka Mate’.

Another common condemnation of the haka is that it gives New Zealand an advantage. Funnily enough, there are fewer assertions about the routines of Fiji, Samoa or Tonga, known, respectively, as the ‘Cibi’, the ‘Siva Tau’ and the ‘Sipi Tau’. Besides, the physical exertion required for a haka, which one source likened to a 400m race, means that you will see the All Blacks collect themselves, huddle up and re-focus before kick-off.

“Do I think it gives them an unfair advantage?” Greenwood asks. “If it does, you have the wrong players on the pitch. Anyone who can’t love that… go and be an accountant.”

Collective responses to the haka have a file of their own. Greenwood was part of the 2005 British and Irish Lions team that, after consulting with Maori elders, deployed Dwayne Peel, their youngest player, alongside their captain to accept the challenge. “When you get battered, people go: ‘What are they doing?’” Greenwood adds. “But we had some pretty sharp players on that pitch and I didn’t hear anyone ask why we were doing it.”

One rather tenuous subplot of the haka is how fines are doled out when opponents break regulations and cross the halfway line. England were sanctioned at the 2019 World Cup when their arrowhead formation encroached too far. Eight years previously at the World Cup final in Auckland, an underdog France side almost brought down the house.

“My favourite one was in 2011 for the World Cup final when France got into a V-shape behind Thierry Dusautoir and stepped forward,” Greenwood says. “I was at Eden Park and turned to my mate and went ‘they’re going to beat them’. They should have done, too.”

England will have devised their own way of meeting the haka in Dunedin this weekend. Embracing its theatre is an inherent part of facing the All Blacks.

Five memorable modern-day hakas from the All Blacks

New Zealand v South Africa, 2005

The inaugural ‘Kapo o Pango’, led by Tana Umaga, bristles with intensity.

Wales v New Zealand, 2008

A stare-down follows the haka as the hosts hold their ground for over a minute, with the Cardiff crowd erupting in response.

New Zealand v France, 2011 World Cup final

France face the All Blacks in a flying V before the World Cup final, foreshadowing a dogged performance led by Theirry Dusuatoir.

New Zealand v Ireland, 2016

Prior to their first ever win over the All Blacks, Ireland adopt a figure of eight in memory of Anthony Foley. They would repeat the formation seven years later for the World Cup quarter-final.

England v New Zealand, 2019 World Cup semi-final

Spread widely enough to earn themselves a fine, England aimed to surround the All Blacks with Owen Farrell smiling at the middle of it all.