Inside anti-doping’s civil war: anger and suspicion spill into the open

At its glitzy 25th anniversary gala in Lausanne last month, the World Anti-Doping Agency screened a slick montage highlighting how it had changed sport for the better. There were images of Muhammad Ali defying Parkinson’s to light the Olympic flame and Pelé lifting the World Cup, before a history lesson – and a promise. “Today Wada is a more representative, accountable and transparent organisation,” explained its director general, Olivier Niggli, “that truly has athletes at the heart of everything we do.”

Not everyone in the room was buying it – one source felt it was too PR-focused, while another raised their eyebrows when Thomas Bach – the president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) – and the former Wada president Sir Craig Reedie picked up awards. However, frustrations with Wada were largely limited to corridor conversations. It turned out to be the relative calm before the thermonuclear storm.

Related: Poison in the pool: why the latest Chinese doping row is proving so toxic

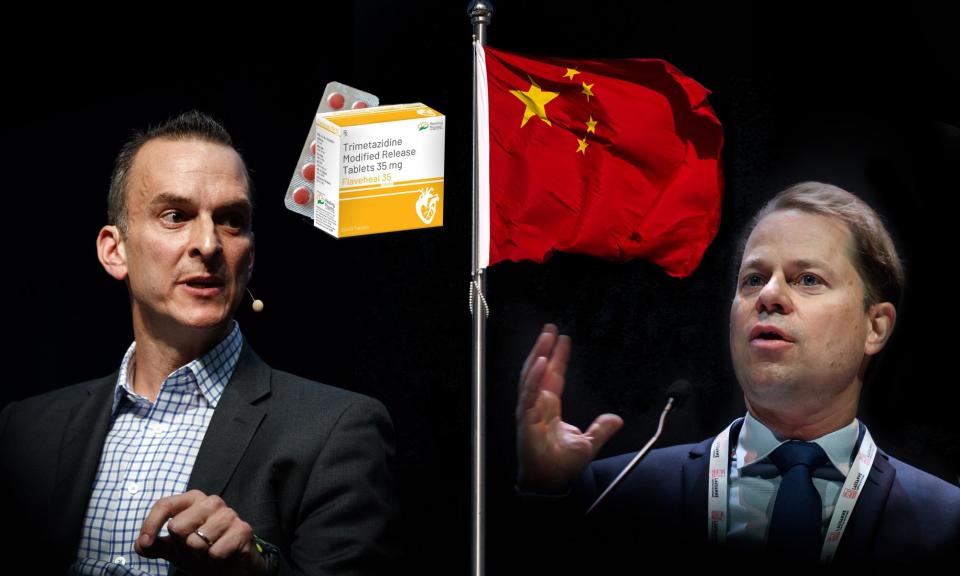

Everything then changed last Saturday when an ARD/New York Times investigation revealed that 23 Chinese swimmers had tested positive for the banned heart drug trimetazidine (TMZ) before the Tokyo Olympics – only to be quietly cleared after the Chinese Anti-Doping Agency found their hotel kitchen had been contaminated. If that wasn’t explosive enough, the chief executive of US Anti-Doping, Travis Tygart, then turned the finger of blame on Wada and Chinada for having “swept those positives under the carpet by failing to fairly and evenly follow the global rules that apply to everyone else in the world”.

Tygart has form for speaking his mind – most notably on Russia – and Wada has tended to ignore him or issue an anodyne response. Not this time. Instead it retaliated by accusing Tygart of “outrageous, completely false and defamatory remarks”.

And with that, years of pent-up frustrations, suspicion and anger – on both sides – spilled out into the open. A week on, anti-doping’s civil war is showing no sign of abating. And increasingly there is a sense that this row is not just about the fate of 23 Chinese swimmers, but the heart and soul of the anti-doping movement too.

First, though, those swimmers – and why Wada didn’t challenge the findings by the Chinese authorities. Here Wada’s position is clear but contested. It says it had “no evidence to challenge the environmental contamination scenario that led to Chinada closing these cases in June 2021” – and that it was advised by external counsel that it would lose any appeal at the court of arbitration for sport (Cas) based on such a challenge.

However, Tygart’s Usada and its allies argue that Wada is not being transparent and hasn’t shown enough investigative zeal, and question why it didn’t press the Chinese intelligence services over why it took two months to find TMZ in the hotel kitchen. As Rob Koehler, the chief executive of the pressure group Global Athlete, puts it: “The athletes I speak to are severely pissed off, they’re disheartened, and they want accountability and answers. Athletes feel that down because once again, they feel like they’re held to a higher standard than powerful countries.”

Richard Ings, the former chair of the Australian Anti-Doping Agency, dismisses any notion of severe wrongdoing by Wada. “I don’t believe that an organisation like Wada would be covering up doping cases in China,” he says. “Wada got burnt pretty badly with Russia. I think they are unlikely to be caught unawares again with another country. What makes the most sense is that Wada got a report from Chinada and with the limitations with travel in Covid, they sought further legal advice and decided any challenge would not prevail in Cas.

“I think it’s important to remember that World Aquatics had the same brief and the same right of appeal and they also did not do so.”

So what does the case say about the wider anti-doping system? To answer that, the Observer spoke to more than a dozen senior anti-doping executives, lawyers and officials, most of them on a confidential basis. While there was little consensus, some trends did emerge.

The first was a general sense that Wada was shouting less about going after cheats than previously. As one senior figure put it: “Wada is not talking about kicking down the doors of dirty athletes. From a generous perspective, it is instead trying to establish a compliance regime that actually gives them a sense of who the bad people are.”

That, they conceded, wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. “But,” they added, “is Wada any good? I’m not convinced. I think there are some good people there. I like Günter Younger, from intelligence and investigations. But, aside from that, there seems to be a sense of plodding along.”

In a statement, Wada rejected the suggestion that it was focused too much on compliance rather than catching cheats: “It is not a case of one or the other.”

Second, as many pointed out, it is worth remembering that Tygart and Wada have history. The American was the most vocal critic of Wada during the Russian doping scandal, when he accused it of being too slow to investigate the allegations of state-sponsored doping, questioned its closeness with the IOC and condemned it for not doing enough to protect clean athletes.

Yes, he upset a lot of people in Wada and the IOC. But Tygart was proved correct. So can you really blame him for raising the alarm here too? His detractors, however, believe his comments are part of a wider geopolitical conflict between the United States and China – and reject the notion that China is Russia mark II.

It is also worth reflecting that when the US government passed the Rodchenkov Anti-Doping Act in 2020, it further strained relations. The act allows the US to target doping networks – including doctors, coaches and drug suppliers – involved in international competitions where American athletes compete – encroaching into Wada’s territory.

A third trend: not everyone is happy with Witold Banka’s stewardship since he took charge of Wada in 2020. Some were surprised that he extended his initial presidential term from three years to six last year, with one source saying it has “super pissed people off”.

Others wondered whether the latest rows showed he lacked the savvy to keep figures such as Tygart, who has a track record of catching cheats, onside. As another source puts it: “The job is great for him. Is he great for the job? I don’t think so.”

Some also believe that Wada’s criticism of Tygart showed the organisation is less tolerant of dissent, but that was rejected by a spokesperson. “Wada is used to constructive criticism and reasonable comments,” they said. “However, when you are openly accused of bias towards a particular country and of covering up doping, without even a shred of supporting evidence, it ceases to be reasonable and we are duty-bound to defend ourselves against such attacks, many of which are politically motivated.”

For good measure, the spokesperson also rejected any suggestion that Wada lacked the appetite to go after powerful countries. “That couldn’t be further from the truth,” they added. “We always stand ready to confront and stop those who would cheat the system, no matter where they come from.”

Meanwhile don’t expect a detente any time soon. On Thursday Wada announced an independent investigation into its handling of the case of 23 Chinese swimmers. Usada’s response? To question whether it would be truly independent.

It is all a far cry from events at the 25th anniversary gala a month ago. That evening, Banka told delegates: “Together we are raising the game, ushering in the next quarter century with a single mission as one team.” Now, however, that team feels more split than ever.