Macclesfield Town's demise was signposted but that doesn't make it less painful

The announcement was shocking but registered as no surprise. Like the £500,000-plus the club owed its creditors, Macclesfield Town had been on borrowed time. After a long series of court dates and adjournments, Judge Sebastian Prentis, via a virtual hearing, wound up the club on Wednesday in a specialist insolvency and companies court.

It will be the fans who suffer. A Macclesfield Town supporter does not dream of the Champions League or signing Gareth Bale on loan but it is the shared camaraderie of icy afternoons on the Star Lane End or a 500-mile round trip by coach to Torquay that will be lost. And in their own way, Silkmen fans followed a club with much to be proud of, as a powerhouse of the non-league scene in the late-1980s, a Football League club against the odds after that and somewhere that gave three Black managers in Sol Campbell, Paul Ince and Keith Alexander opportunities.

Related: Macclesfield face extinction after being wound up with debts of over £500,000

There is little time to save any semblance of a local institution formed in 1874 and thus older than the Manchester giants that loom 20 miles up the A6. And few saviours. Joe Sealey, a local businessman, has been circling for months and was interviewed on Wednesday at the Moss Rose. He said he was in negotiations to buy another club, though he admitted “half a million pounds for a club of this stature is not bad”.

Stature? Sealey, the son of Les Sealey, the late former Manchester United goalkeeper, would be taking over a severely distressed asset, a hollowed-out shell. Putatively, the club is in the National League, having been relegated from League Two after a count-back of points per game and the EFL successfully challenging a ruling that had set Stevenage for the drop. The 17 points the Silkmen were deducted for repeatedly failing to pay their players cost the club their Football League status.

In the eyes of Macc fans, and taking into account the EFL and football authorities allowing the situation to snowball after multiple intimations of disaster, one person should shoulder the blame. Amar Alkadhi, a London-based Iraqi telecoms entrepreneur, has been involved with the club since the mid-2000s and was once viewed as a benevolent enough if not exactly spendthrift owner. Money had always been tight but it was success, a promotion from the National League at the end of the 2017-18 season, that was the beginning of the end.

A return to the Football League after six years was a huge achievement but two of the club’s mainstays were soon gone. Arighi Bianchi, the venerable furniture store that towers behind the train station and sells its wares to the bourgeoisie of London and Manchester, was removed as shirt sponsor in favour of Zaki Artist Management, a DJ booking agency based in Ibiza. And, even more unthinkably, “Mr Macclesfield” himself, John Askey, the manager, associated with the club since 1984, one of their finest ever players, walked out to join Shrewsbury.

That Askey had left for more money at Shrewsbury was the word, but the truth of his departure was spelled out in the court hearing on Tuesday. He was owed more than £170,000 by the club and by extension Alkadhi. Two seasons of farce followed, including Campbell’s 10 months at Moss Rose, which saw him rescue the club from relegation and yet walk away in August 2019, later citing a £180,000 debt for unpaid wages.

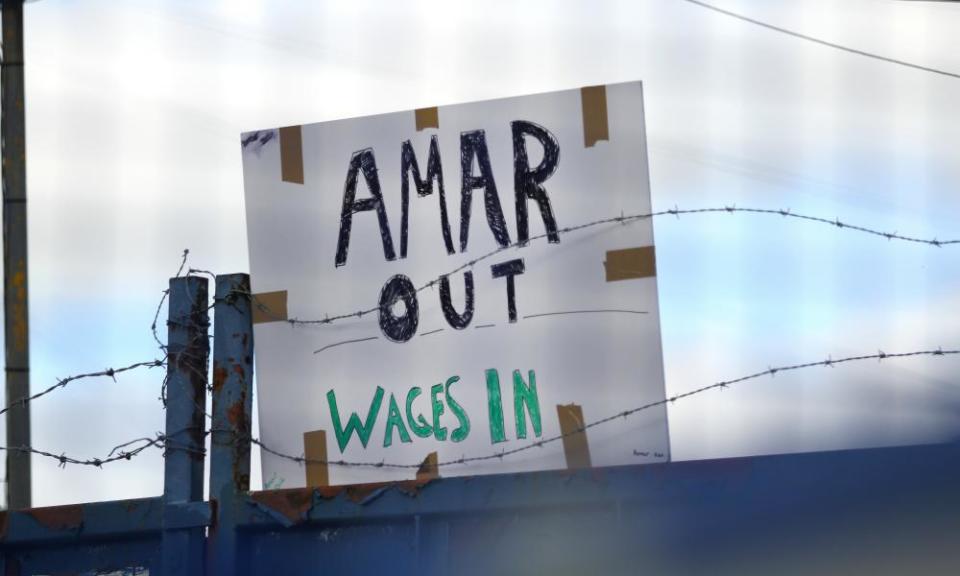

Even before Covid-19’s removal of match-day revenue and cash flow pulled the rug, extinction loomed large. In November, a home FA Cup first-round tie with Kingstonian was boycotted by fans and players; the Isthmian League side beat a group of youth-team teenagers 4-0 with more Macc fans outside the ground than in. And the points deductions piled up. Alkadhi, who is said to conduct his business affairs exclusively via WhatsApp, remained absent. “Amar Out” read the scoreboard after Macc’s 1-1 draw on Boxing Day with Grimsby, evidencing open rebellion behind the scenes.

Macclesfield’s demise, like that of Bury and with Wigan now also on the brink, spells out the difficulty of life in the shadows of United and City and amid the rising economies of scale of running even the smallest clubs in professional football. Sir Alex Ferguson, Rio Ferdinand and Wayne Rooney, whose brother John and cousin Tommy played for Macc, have been regular visitors to the Moss Rose but the stardust never quite rubbed off.

An average attendance of less than 2,000 was always among the lowest in the Football League, and the club’s two spells there have been of significant struggle against the tide, barring one promotion to the third tier under Sammy McIlroy that famously brought Manchester City to town in September 1998. Macclesfield have always walked a financial tightrope and been a misstep away from the brink.

The town of Macclesfield itself is, as the New Order drummer and Silkmen fan Stephen Morris put it, “a mill town that had lost the adjective ‘thriving’ somewhere along the way”. Its high street is pockmarked by boarded-up shops. The football club, like the old Majestic cinema and the many closed pubs on the London Road walk up to the Moss Rose, appears destined to become another lost community asset.