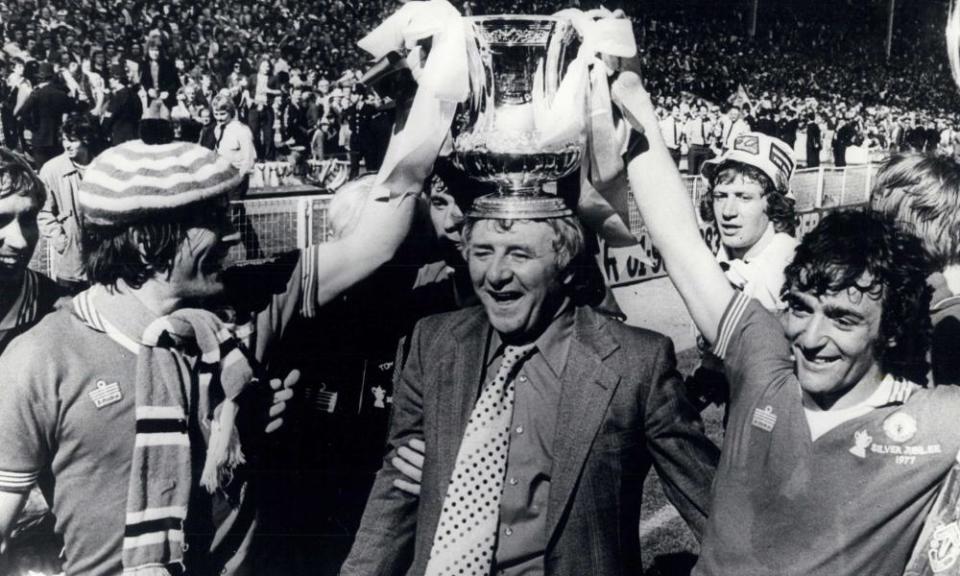

Tommy Docherty obituary

Tommy Docherty, who has died aged 92, often liked to say that he had “had more clubs than Jack Nicklaus”– a joke that referred not to his successful playing career as a hard-tackling, intelligent international right-half, but to his peripatetic existence as a manager. Beginning with six years at Chelsea in the 1960s, which started brightly but ended in chaos, he had more than a dozen spells in management, including at Aston Villa, Queens Park Rangers, Derby County, Porto, Wolverhampton Wanderers and his own national side, Scotland. His most celebrated period came at Manchester United in the mid-70s.

Although he was one of the highest profile football managers of his generation and remained highly marketable well into the 80s, Docherty’s returns were actually rather slight, amounting over three decades to a Second Division title and FA Cup win with Manchester United and a League Cup victory with Chelsea. He took all the ups and downs with his trademark ebullient humour, and was ever willing to tell a story against himself. In 1967, after the Chelsea directors had called him to the boardroom and told him he was being released, he disappeared momentarily before returning with several bottles of champagne, with which he cheerfully toasted those who had just dismissed him. His enemies would say of him that you always knew he was lying because his lips moved – but he would make jokes about that as well.

The son of Georgina, a cleaner, and Thomas, who worked in an iron foundry, Docherty was born into poverty in the Gorbals area of Glasgow and joined his first club, Celtic, in 1948, after national service. At Celtic Park he came under the aegis of the English coach Jimmy Hogan, who had managed Austria’s national team to unprecedented levels of success and was considered one of the great pioneers of the game on the European continent. Hogan was an elderly man by then, and was not always taken seriously in Britain. But the young Docherty was both open-minded enough and sufficiently bright to profit from Hogan’s refined techniques, which he eventually carried into his own managerial career.

He did not spend long with Celtic. In 1949 he was bought by Preston North End. Docherty made his debut as an outside-left, but soon settled into the right-half position as the ideal successor to another blond, uncompromising Scot, Bill Shankly, himself beginning an outstanding managerial career. Preston had slipped into the Second Division after several impressive years in the First, but in the 1950-51 season Docherty helped them back up, playing in all 42 games; as he would the following season.

He won the first of his 25 Scotland caps in 1951 against Wales, and in 1954 played in both of Scotland’s World Cup finals games in Switzerland, the first narrowly lost 1-0 to Australia, the second a 7-0 rout at the hands of the irresistible Uruguayans. He travelled to Sweden for the next World Cup finals in 1958, but did not get a game, unable to displace the veteran Eddie Turnbull of Hibernian, who had dropped back from inside-left.

Docherty regained his international place the following season, however, winning another three caps while with Arsenal, whom he had joined in 1958. At Highbury he also figured sometimes successfully at centre-half. The 1961-62 season saw him move across London to Chelsea as a player-coach, making just four more appearances in the First Division and finishing his career having played more than 400 league games for his various clubs.

The Chelsea manager, Ted Drake, was clearly coming to the end of his reign and in January 1962 Docherty succeeded him. It was too late to save Chelsea from relegation, but the following season the new manager, who was always ready to give youth its fling, bought and sold frenetically on the transfer market and gained promotion on goal average.

Brian Mears, then a Chelsea director and later chairman, reported that his new charge was “enthusiastic, swashbuckling, funny, outrageous, successful, rebellious, abusive, unbelievable”, and “always his own worst enemy”. Docherty, he said, acted on impulse, “promising players one thing and then demanding it from the board, making fun of people behind their backs, playing practical jokes, saying ridiculous things to the newspapers, slagging players off one day and then asking them to die for him the next”.

Clashes with players were a feature of his managerial life. At Chelsea, Terry Venables, then a rising young player, constantly locked horns with his manager, and was eventually sold to Spurs. He was also one of eight Chelsea players controversially sent home by Docherty from Blackpool in 1965 before the penultimate game of the season. Docherty insisted the players had gone out at night without permission; they argued the contrary, and accused Docherty of courting publicity. Another future manager of renown, George Graham, was among the eight, and although Peter Bonetti, the acrobatic goalkeeper, was not, Docherty managed to fall out with him too.

It would all eventually end in tears, although the club won the League Cup in 1965 and reached the 1967 FA Cup final against Tottenham Hotspur. That summer Docherty was suspended for 28 days by the Football Association over an altercation with a referee during a club trip to Bermuda, and his fate at Stamford Bridge was sealed. In October he officially resigned and was replaced by the markedly less exuberant Dave Sexton, who took Chelsea on to win the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1971.

Docherty skidded down the league to manage Rotherham United in the 1967-68 season. Next came the first of his two spells with Queens Park Rangers, with whom he lasted for just three league games. Second Division Aston Villa promptly appointed him in December 1968, and he saved them from relegation. However, despite heavy expenditure under a new board of directors, the following season was disastrous and he was on his way again in January 1970 as his side languished at the bottom of the league.

Technically this was the first time he had been sacked, but he was out of work only for a month, joining Porto in Portugal. He stayed there for almost a year and a half before resigning in May 1971, having failed to break the stranglehold of Benfica and Sporting Lisbon in the league.

Returning to Britain, he briefly became assistant manager to Terry Neill at Hull City, but left to become the caretaker manager of Scotland, taking on the job permanently before the end of 1971. It was his work with Scotland that landed Docherty the manager’s job at Manchester United, as the Old Trafford hierarchy were looking to replace the incumbent, Frank O’Farrell, and two of United’s Scotland internationals, Willie Morgan and Denis Law, gave Docherty enthusiastic references.

So it was that in 1972 he began his hectic five years at United. History promptly repeated itself; they went down to the Second Division at the end of his first full season. But Docherty’s attacking style was matched to the traditional expectations of the Old Trafford crowd, and green shoots began to appear in the spring of 1974.

In the Second Division he threw previous caution to the wind, used a fast young winger in Steve Coppell, from Tranmere, and sped back into the First Division. The following season he signed Gordon Hill from Millwall and defied conventional wisdom by using two wingers. In 1976 United’s rejuvenated team reached the FA Cup final, only to lose, sensationally, to Second Division Southampton. Docherty promised they would be back the following year, and so they were, this time beating the favourites, Liverpool, 2-1.

The internal fallout from that victory was rather typical of Docherty’s rule. The manager had promised the team £5,000 in cash if they won, and handed it to the skipper, Martin Buchan, after the match. Buchan gave it back to him for safekeeping and never saw it again. There were many other alarums and excursions during his tenure, many of them prompted by Docherty’s penchant for wheeling and dealing.

When he arrived at the club he had set about buying and selling with his usual abandon, and among those he had jettisoned was Law, who became deeply embittered and left for Manchester City, in due course scoring the goal that sent United down to the Second Division. George Best also dropped out of the club, and there were harsh disagreements with Morgan, Alex Stepney and Pat Crerand, who was by then a managerial assistant.

“The Doc”, as he was known, also had a reputation – in which as a manager he was hardly alone – for treating his favoured players generously, but those whom he excluded abominably. He even became involved in a failed libel action against Morgan that led to a charge of perjury, of which he was acquitted.

However, it was the public revelation of Docherty’s extramarital affair with Mary Brown, wife of the club physio Laurie, which led to his departure. He was sacked in a blaze of national publicity in July 1977 and replaced by the same man who had followed him into the Chelsea manager’s job, Sexton.

Despite the scandal attached to him, Docherty remained employable for some time afterwards: at Derby for two years from 1977 to 1979; again at QPR; at Preston, fleetingly, in 1981; and at Wolves, by then a sinking ship, in 1984-85. Once he retired from football management he became a successful after-dinner speaker, and through all his triumphs and disasters his sense of humour remained unalloyed.

He is survived by Mary, whom he married after his first wife, Agnes, divorced him, and by six children, three sons, Tom, Michael and Peter, and a daughter, Catherine, from his first marriage, and two daughters, Lucy and Grace, from his second.

• Thomas Henderson Docherty, footballer and manager, born 24 April 1928; died 31 December 2020