Trudy Ederle overcame poison, jellyfish and six-foot swell to become first woman to swim Channel

On day one of preparation for her new swimming movie, Star Wars heroine Daisy Ridley met her expert coach, Olympic silver medallist Siobhan-Marie O’Connor. In an unconventional ice-breaker, O’Connor asked Ridley to swim two lengths of a standard pool. Ridley blanched at the idea. “Her response was ‘Oh, my gosh. Fifty metres in one go?’,” O’Connor recalls.

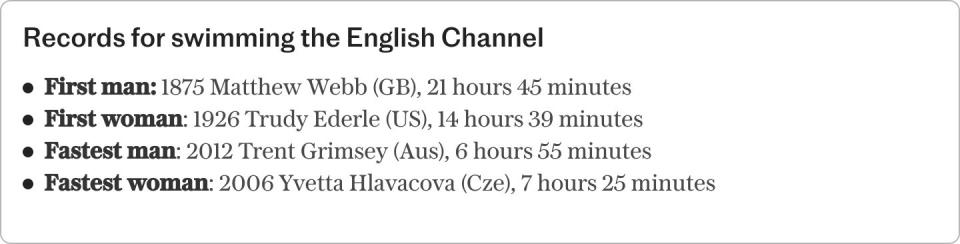

Ridley’s incredulity matched the global mood in 1925, when Gertrude ‘Trudy’ Ederle first took on one of the most intimidating feats in sport. Only five men had swum the English Channel in the half-century since Capt Matthew Webb first completed the crossing. For a woman to do it? Unthinkable.

Even Ederle’s own trainer, a Scottish misogynist named Jabez Wolffe, scoffed at her chances. “I have told her that this marathon swim is different from anything she has tried,” Wolffe said. “But what man can argue successfully with a woman?”

Fortunately for Disney+ and their glossy movie Young Woman And The Sea, Ederle was not easily dissuaded. Since the moment her father, Henry, first tied a clothesline around her waist and dangled her off a pier in New Jersey, she had become wedded to the water: a virtual amphibian. And, thanks to her proximity to the fledgling Women’s Swimming Association – a mould-breaking club who trained in nearby Brooklyn Heights – she saw sport as an equal-opportunities affair.

“I definitely resonated with the story,” O’Connor says. “When I read the script, I was really moved and felt very lucky to be involved. I like that quote, the one that says, ‘You stand on the shoulders of giants who came before you’. Trudy is one of those people.”

While it might seem unchivalrous to compare Ederle to a racehorse, Glenn Stout’s original book (also called Young Woman And The Sea) feels reminiscent of Laura Hillenbrand’s 1999 bestseller Seabiscuit.

Here were two massive inter-war celebrities. Hillenbrand claims that, in 1938, Seabiscuit earned more column inches than Roosevelt, Hitler or Mussolini. As for Ederle, she became the world’s most famous woman for a couple of years in the mid-1920s. And yet, in both cases, the protagonists were largely forgotten before being rediscovered by a pair of enterprising authors, then fast-tracked to the cinema.

Like Seabiscuit (2003), which starred Tobey Maguire and Jeff Bridges, the Ederle biopic has a stellar cast. Ridley’s sidekicks include Christopher Eccleston as the scheming, spats-wearing Wolffe, plus Stephen Graham as scantily clad Channel swimmer Bill Burgess.

As a teenager, Ederle had been unstoppable in the pool. Across the course of 1923 – the year she turned 18 – she broke no fewer than seven world records. Yet her sheen faded when she travelled to Paris for the 1924 Olympics and came back with a disappointing haul: two individual bronzes, plus a consolatory gold in the freestyle relay.

The attempt on the Channel was a way of regaining some pride, but it backfired initially. On her first attempt, staged in August 1925, Ederle floundered somewhere around the nine-hour mark, still 6½ miles shy of Dover. Stout suggests that the villainous Wolffe had deliberately sabotaged her by poisoning her tea. Outlandish as it might sound, this theory was widely circulated at the time. As one contemporary reporter put it: “Gertrude Ederle hints that a dastardly plot conceived in the fiendish noodle of an English trainer robbed her of victory.”

Looking to reinvigorate her quest, Ederle sacked Wolffe and hired Burgess instead. But the stakes had already climbed. The Washington Post’s sporting columnist Dorothy Green wrote that “woman’s place, though it may not be in the home, is certainly not in the English Channel”.

Ederle spent the winter of 1925-26 stewing over her near-miss. Assisted by her sister Meg, she experimented with more hydrodynamic swimming costumes, coming up with what Stout described as “the world’s first bikini”. And when she set off for a second attempt, on Aug 6, 1926, nothing was going to stop her. Not the cold water. Not the treacherous currents. Not the winds that whipped up a six-foot swell. Not even the swarms of stinging jellyfish. Forging on at a reliable pace of 28 strokes per minute, Ederle crossed in just over 14½ hours. She had smashed the previous record, which belonged to Boston’s Charles Toth, by more than two hours.

An instant sensation in her home country, Ederle resonated internationally as well. In Berlin, the Zeitung am Mittag hailed “new and conclusive proofs of the athletic emancipation of the once weaker sex”. In Paris, Le Figaro dubbed her “the most glorious of the nymphs”. On her return to New York she was cheered by an estimated 250,000 people during a ticker-tape parade through the streets of Manhattan.

Many contemporaries expected Ederle’s feat to be a game-changer. “As far as physical strength is concerned,” swimming coach Tom Robinson said, “women have shown a prowess equal to men.”

Yet the patriarchy has proved more resilient than Robinson expected. As O’Connor notes: “The Olympic 1500m freestyle was a male-only race for decades. It wasn’t until Tokyo, three years ago, that the women got a chance.”

O’Connor’s work on Young Woman And The Sea, which involved not only coaching but also some screen time as a WSA swimmer, has brought home the value of role models, too.

“When I was swimming all hours in my school days, I wasn’t sure if I was doing the right thing, because most of the other sporty girls stopped training in their teens,” she says. “It really helped that I watched Rebecca Adlington win her two gold medals in Beijing, because I could see a British woman reach the pinnacle of the swimming world.

“In Trudy’s time, it was frowned upon for women to just be in the water and swim, let alone to take on a challenge like she did. She was such a trailblazer and it was incredible to play a small part in telling her story.”

So, what of Ridley’s pool prowess? “Daisy is very athletic,” O’Connor replies. “She just had to develop her specific swimming fitness. Before long, she was getting through three or four sessions a week, and covering something like two kilometres [80 lengths of a 25m pool] in each one.

“There are a few body doubles in the movie, but the majority of the underwater shots are all Daisy. Her dedication was amazing.”

The result is a fitting tribute to Ederle’s ground-breaking, record-smashing swim.

Young Woman And The Sea will be in cinemas from May 31