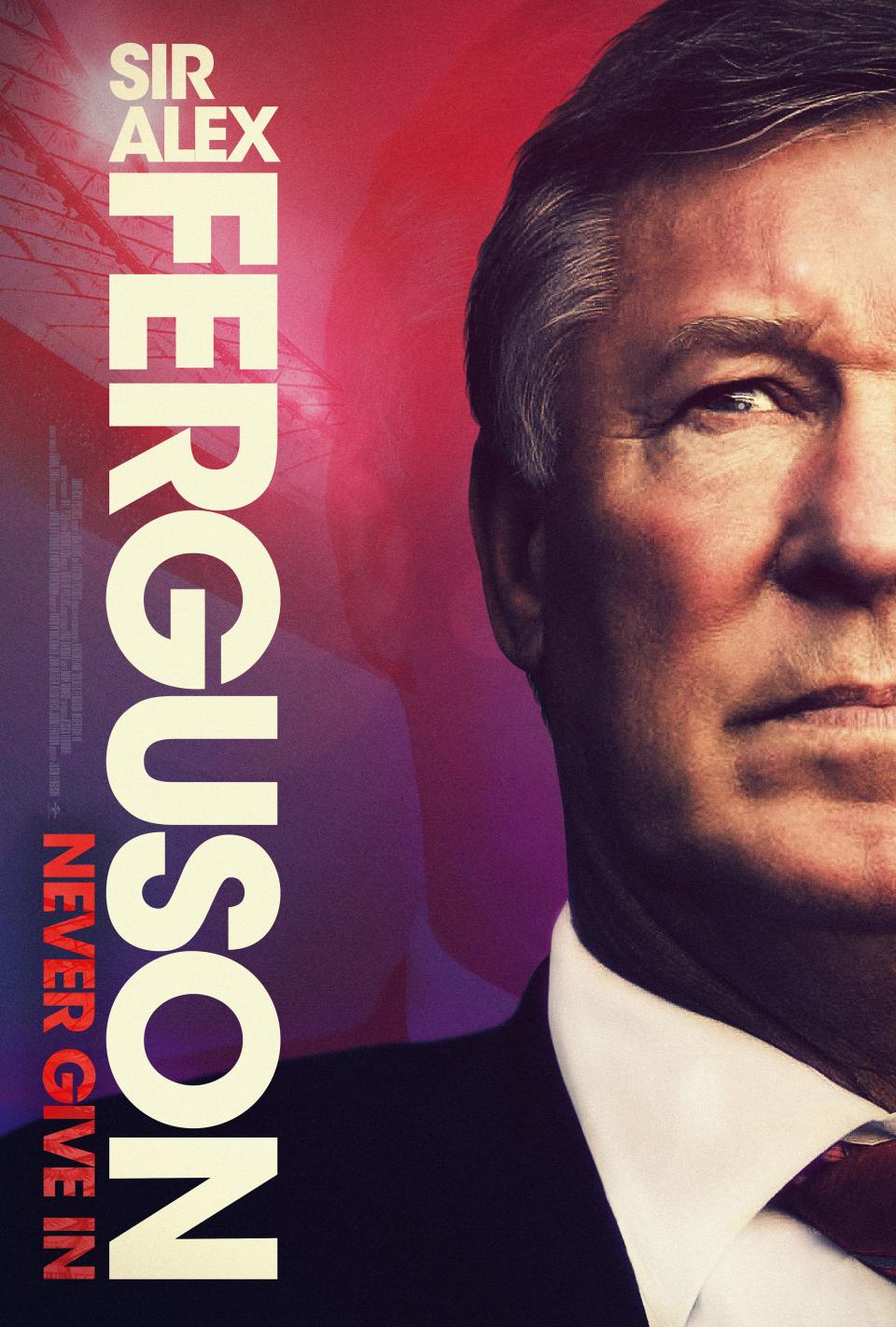

Understanding Sir Alex Ferguson, the man behind the success and trophies

The new documentary Sir Alex Ferguson: Never Give In opens with an ambulance winding through country roads, scored by a call made on 5 May, 2018.

The voice you hear speaking to the emergency services is Jason Ferguson. At 6:30am that morning he had taken a call from his mother, Cathy, to tell him his father had collapsed.

He had made one other call before dialing 999: to Manchester United’s club doctor at the time who, within two questions, determined Jason’s father had suffered a brain haemorrhage and urged him to dial 999 as soon as possible.

In October later that year, while Jason was sat in an editing suite fulfilling his duties as director of the documentary, a runner came in and handed him a CD. Bemused at first - “when was the last time you held a CD?” he asks The Independent - he realised he now had the audio in his possession. He asked his editor, Gregor Lyon, to step outside so he could listen back to it alone.

“My recollection of making the call was that I was quite in control and dealt with it reasonably calmly,” says Jason. “So I was a little bit surprised, maybe shocked to hear that I was quite emotional. When I heard it for the first time… well, I went for a walk afterwards, put it that way.

The most striking bit of the call, signposted by the most significant break in Jason’s voice, is when he has to use his father’s full name. “Alexander Ferguson”.

There is something about saying a parent’s full name that carries a unique dread. A moment when you have to regard them solely as a human being, stripped of context and, in such a scenario, at their weakest. Even for those of us without a personal relationship to the man, hearing Alexander Ferguson instead of Sir Alex, S’Alex or simply Alex is a jar to the senses.

The sequence sets the film winding away on dual courses, very different to the singular one it was set to take when planning began in 2016. A colleague Martin O’Connor, who became an executive producer on the film, suggested Jason should start collecting audio interviews with his father, if only as a record for the family to have. After 18 months, he had the guts of a feature picture. And then, after that fateful May, another vital strand.

“It introduced that whole second timeline,” Jason says. “You’ve got chronology of his life and you’ve got the story of the brain haemorrhage.” Before then, preliminary work had shown him that everything his father created during his life, including most of what we would come to know as Sir Alex Ferguson’s legacy, had come through overcoming hardship.

“Our very first treatment pre-brain haemorrhage, that was how I felt. For all the public perception of him as all the success and trophies, for me, he’s been defined by how he has dealt with adversity. And once he had recovered, that element of his life tied into that core theme.”

The result is 110 minutes of man rather than ball. Football is a huge part of the film: how could it not be when the subject matter is so woven into its history as a manager of 39 years, who won league titles in four different decades. But the open goal of retrospection set-up by a steady stream of celebration is avoided, though not completely. Only four of the 11 interviews conducted are with those associated with football. Five family members and two doctors make up the rest.

Perhaps only a son could indulge the creative audacity to do such a thing. But the achievement is better for it. In sport we have a knack - an unhealthy one, at times - of reverse-engineering what we see on the field to extrapolate personality and motivation. Here we get into why Sir Alex came to be rather than how.

This is all helped by Jason’s own realisations during the process. Nothing came as a surprise necessarily, but the lesser known aspects of his father’s early life were fully revealed to him, too.

“I was 11 when they (Aberdeen) won the cup winners cup against Madrid,” he says. “No one was really bothered that my dad was a manager at the local team at Aberdeen. But Manchester United was a different kettle of fish. The scale of the club, scale of the stadium, the media attention. I’m getting older at the same point and I’m seeing him getting that first Champions League, the three league titles in a row, three times. Then he gets a stand named after him, which for me was one of the most incredible things I experienced. But a lot of the early stuff, before I was born, I knew of but not as much as I found out.”

One of the more profound personal moments was realising just how badly things went at Rangers. Sir Alex grew up in Govan, a working-class district of Glasgow in the shadow of the Ibrox Stadium. He dreamt of playing for the club and got his wish for two years, and no more.

It started acrimoniously when he was quizzed by a Rangers director on his marriage. Cathy was Catholic and Sir Alex, a Protestant, was asked if they got married in a Catholic Church. He confirmed it was in a registry office, but holds regret to this day that he did not tell the director to “f*** off”, not least because when put on the spot, he did not stand up for his wife.

The end was as bad, scapegoated for a chastening 4-0 defeat to Celtic in the 1969 Scottish Cup final. When Aberdeen beat Rangers in the 1983 Cup final, he tore into his players, lamenting an under-par display that drew confusion at the time. When pressed in the film about the motivation behind his tone, he cedes, grudgingly and with obvious emotion, that his anger was rooted in not being able to inflict enough revenge on the club that almost broke him.

“I don’t think I’d fully realised the extent to which the experience he had at Rangers impacted him,” says Jason. “When I asked him in the film about that rant after the ‘83 cup final when he goes berserk, I asked him if it was about - being the best team in Scotland or hammering Rangers? It was an exploratory question.

“It wasn’t like we were sitting at Sunday dinner listening to him rant about Rangers, do you know what I mean? But I knew it scarred him: that experience, after growing up supporting them and played for them, at a time when Celtic were winning everything. Now looking back, I know he would have loved to have played with Rangers for a number of years. But it wasn’t something that came up. I knew there was something there but I didn’t know it ran quite as deep.”

Sir Alex chose to stay as far away from the project as possible beyond his own interviews and the odd consultation on archive imagery and footage, particularly from the early days in Govan which required a more personal touch. Yet the unhindered access between father and son meant issues that usually might have waited until wider release to be rectified were addressed privately and promptly.

One in particular was a grudge forged between Sir Alex and Gordon Strachan. The pair worked together at Aberdeen and Manchester United, but both stints ended on poor terms.

Jason knew Strachan was an integral part to the Aberdeen story, a part of Sir Alex’s sides that brought seven trophies back to Pittodrie. But he also had first-hand experience of the bad blood still festering decades on.

“The Strachan one, I wasn’t sure how that interview was going to go. My brother (Darren) is a coach, and his assistant for years was Gavin, Gordon’s son. They’d bump into each other at occasional games. It was OK, but, you know, it wasn’t overly warm without necessarily being overly cold.

“The interviewees were quite carefully selected, I was conscious that I didn’t want to crowd the film with talking heads. But I wasn’t sure what I was going to get from Gordon.”

Jason employed a tactic with his subjects where he sent a list of topics but, when face-to-face, would tack on a final question focussing on the brain haemorrhage.

“When it came to Gordon, it really hit him. He wanted the chance to sit down and sort it out and look back upon the success they enjoyed and enjoy it.”

At the end of their session, as conversation continued, Jason realised an opportunity to right a wrong. Once Strachan had left, he went to see his father and relayed the conversation. Sir Alex got in touch and, a few days later, the pair met for lunch.

This now quashed grievance was one of a number of revelations the film brought to Sir Alex himself. He had always been known as someone to dispose of bad memories. Jason realised just how much so when it came to discussing the many difficult junctures one would expect in a life of 79 years and the chosen profession.

Prompts and reiterated questions drew out the ill-feeling with Rangers and the tough early periods at Old Trafford. Similarly, he had no recall of the month or so after his brain haemorrhage beyond a period where he temporarily lost his speech and feared his memory might leave him for good. When Cathy relays understanding that he could not be there to share the parenting load, Sir Alex cannot seem to get over the sorrow of leaving it all to her.

Three weeks before completion, he was shown the film in London. During the screening, Jason flittered between the screen and his father’s face. The emotional impact was clear.

“When he was having bad days at Manchester United, it was difficult to get stuff out of him around that because I think he’s just boxed it and put it away. I’m confident he’d done exactly the same with the brain haemorrhage.

“So although he’d done these interviews, he could detach from the experience in a way. But when he’s watching himself going through all that, and hearing stuff from the doctors he was not aware of. He didn’t know there was an 80 per cent chance he was not going to survive.”

Once the screening had ended, Sir Alex sat back in silence. A nervy Jason, brothers by his side for support (older brother Darren and his twin, Mark), eventually summoned the courage to ask what he thought. “It’s me,” offered Sir Alex. “Warts and all, it’s me”.

A month later, before the film went into post-production, Sir Alex watched it again at his home with Cathy by his side. Both assumed this would be a football film. And though during the process they became aware that it was bigger than that, they were struck by what was, essentially, a documentary on them and him.

There is still plenty to satiate those looking for a football hit. Footage of Sir Alex during his playing days as a lithe, sharp-jawed finisher are warm, along with golden nuggets scattered throughout. The clips of his Aberdeen squad training in public parks, car parks and even the beach because they did not have their own training ground is a particular delight.

But they are also kind of not the point. Or rather - the succession of trophy lifts , touchline jives and embraces enhance the broader picture.

“My very first objective was to make a film that wasn’t about football. Really, to make a film that could resonate with people who don’t have any interest in football. It’s a story of a man’s life who happened to work in football.”

He may be the godfather of modern British football. But, as Never Give In showcases with light and shade, he was a son, husband and father before all that.

Sir Alex Ferguson: Never Give In is in UK cinemas from 27 May and on Amazon Prime Video from 29 May.

Read More

Her Game Too raises awareness about the sexist abuse experienced by female football fans

Paul Pogba and Amad Diallo hold up Palestine flag after Manchester United’s draw with Fulham

Manchester United left to rue complacency against Fulham after Edinson Cavani’s stunning lob