Why womens football was banned for 50 years – and is only just recovering

Please note: This article first appeared in the December 2016 issue of FourFourTwo

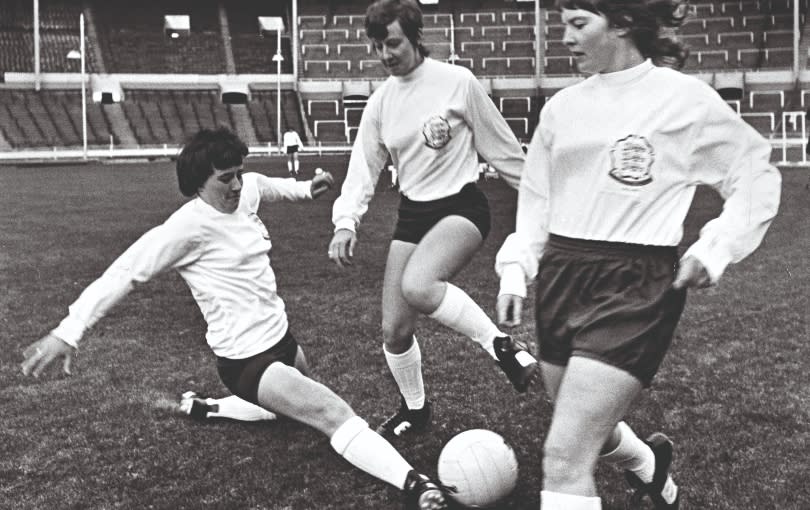

A 12-year-old girl sat on a bus, flanked by her parents, en route from Prescot to Manchester for a football match. She wasn’t going to watch; she was going to play. Unremarkable? Today, certainly. But it was the 1950s, and girls and women were under strict edicts not to play – from none other than the FA.

That 12-year-old girl was Sylvia Gore. She had always loved football, and as a child would kick a ball around with her father and uncle, learning the techniques like millions of other children the world over. “The local football team, Prescot Cables, used to look for me at half-time so I could come on and kick a ball in the goal – they accepted it,” Gore said in May 2016. “A lot of men up and down the country didn’t.”

The FA’s ban on women’s football began in 1921 – a kneejerk reaction to its popularity. The world-famous Dick, Kerr’s Ladies – plus a handful of other outfits – had helped to fill the gap left by the Football League’s hiatus during the First World War, and attracted huge attendances to their games as they raised money for charity.

Up to this point, women’s football had been running almost parallel to the men’s game. A trailblazing player using the pseudonym Nettie Honeyball had formed the British Ladies’ Football Club at the end of the 19th century, and her team toured the country to play exhibition games. Although spectators may have originally turned up to delight in the undignified spectacle, reports from the time suggest they found themselves enthralled by the quality of play.

Out now! A Lionesses special...

These games were intermittent, though, and didn’t detract or distract from the important business of men’s football. Dick, Kerr’s Ladies and their contemporaries were the real threat. The FA lost patience with the women after Dick, Kerr’s and St Helens brought 53,000 fans through the Goodison Park turnstiles on Boxing Day 1920, believed at the time to be the largest gate at any football match in England since records began.

One year later, English football’s governing body passed a resolution declaring the sport “quite unsuitable for females” and informing men’s clubs that they should refuse to let women play at their grounds. The achievements of Dick, Kerr’s Ladies were pushed into the shadows by a footballing establishment that was embarrassed by women’s success.

Gail Newsham, a footballer herself in the 1970s, became the historian of Dick, Kerr’s Ladies. Her labour of love was to chronicle a half-century of clandestine sporting history that had been ignored as best as possible by the football authorities. Growing up in Preston, she’d heard her father talk about watching women play. A local celebration in 1992 gave her the chance to bring Dick, Kerr’s alumni together.

“I advertised in the local press for anybody who knew anybody to get in touch, and the appeal worked,” says Newsham.

“I could not believe it. Hardly anybody knew anything about them in those days, until I did all that research and found out about them.”

As Newsham talked to the players who’d been part of the Dick, Kerr’s phenomenon, she saw photos that made her realise just how popular women’s football had been, contrasting starkly with her own experience of playing during a later era when female footballers were completely ignored. She sighs: “The first lady I saw showed me a picture of the team in the ’50s, and I couldn’t believe the number of people on the touchline. We had the manager and his dog – but nobody else came to watch us.”

Newsham realised that if history was to be preserved, then she would need to do it herself – and quickly. She first published her book In A League Of Their Own! in 1994 and updated it in several subsequent editions as she continued to gather information. She has a particular fondness for the Dick, Kerr’s striker Lily Parr, a chainsmoking tearaway who found the back of the net more than 1,000 times in her career, and whom Newsham wishes got wider recognition.

“When I see statistics and [mention of] the best players ever, nobody ever thinks of the Dick, Kerr’s Ladies and what they achieved,” explains Newsham. “They should be included. Without them, we wouldn’t have this history. Nobody else in the world has got this history except us.”

Even though governing bodies tried to pretend otherwise, there were newspaper archives for Newsham to explore, chronicling the history of Dick, Kerr’s into the 1960s. Much to the dismay of the chauvinists and suits, these female footballers refused to be put off by something as petty as a national ban. Independent organisations governed the game, with the Women’s FA taking control in 1969. Essentially, women’s football was English sport’s best-kept secret.

Yet the ban did hamper them: they were forbidden to use football facilities, were shunted onto rugby pitches, scrubland, schoolfields – whatever they could find.

“We played on park pitches in Frog Lane and had nothing,” Sylvia Gore recalled of her time representing Manchester Corinthians. “We just had an old hut and we used to get washed in buckets of water that the manager brought across. We had no heating, nothing.”

Sue Lopez, who spent all but one season of her 20-year playing career with Southampton, tells FFT that in the 1950s and ’60s, she and many of her Saints team-mates began by joining in with their male friends. “I used to play football with two boys – neighbours of mine,” she recalls. “Whenever they were about, we would all have a kickaround.

“The girls would grow up in these great big tower flats with a bit of green in the middle for a kickaround. That’s why it is good now that the FA have woken up to allowing decent mixed football up to a certain age – because that’s how you learn, by playing with other good people. If it’s just a bunch of girls and only two or three are any good while the rest are hopeless, you’re not going to learn a lot.”

Without girls’ football teams in schools, many of Lopez’s friends and team-mates came to the game late. Often they were excellent in other sports, representing their county or their country, and simply fancied a change. “They were sportswomen, which was good because that gave them a feeling of how to be a sportsperson, whether it be football, netball or whatever, and not to go out drinking on a Friday night,” she laughs.

“We used to play at Southampton Common and it had a pub called The Cowherds,” Lopez continues. “That tells you what it was back in Victorian times: people’s cattle probably did feed on this bit of ground. The football pitches were really rough, with no nets, and we used to play at places like that most of the time. Even when we got another ground – a men’s ground – some of those weren’t that brilliant.”

It’s perhaps not too surprising, then, that talented footballers such as Lopez became frustrated with all the obstacles put in their path. In 1971 she decided to move to Italy, where she played for Roma, albeit not as a professional – just receiving her expenses. She shared a flat with one of her Giallorossi team-mates and enjoyed a year playing on better pitches in front of bigger crowds.

Lopez reluctantly headed back to England when the Women’s FA expressed a concern that players abroad might compromise their amateur status – which would in turn lose the WFA funding from the Sports Council.

“I didn’t really want to come back,” she admits. “They kept on threatening that they would ban people who went to play in Italy. I still had my mum and family and friends here, and I thought: ‘Do I want to stay in Italy forever?’ So I had to make a decision. I thought that I could come back to England to shut them up and then maybe go back out there again later, but unfortunately I didn’t.”

Lopez returned to Southampton the same year she left – 1971 – and helped to shape the team into one of the most impressive forces in women’s football. It coincided with the official lifting of the ban on women playing, but that didn’t mean they were immediately given all the support they required. The FA invited the Women’s FA to affiliate to them, much as a county FA would do, and left them in control, essentially as a network of volunteers with precious little resources. The clubs continued to run themselves as best they could.

“It was difficult to find someone to run the team,” says Lopez. “We never had anyone top-notch, but they were nice people and they did their best. Training was so basic: our warm-up was in a school. We’d just run around the netball court.”

Whenever the weather was bad or if their usual facilities were unavailable, the female players had to take a more innovative approach to training. One of the volunteers worked at a local post office and came up with a bright idea when the team couldn’t even find a school gym to use. Lopez remembers: “He said, ‘Oh: I’ll open up the post office where all the post goes in.’ There were all these bags and we’d have a run around them. At least we were in the warm. Those are the lengths we would go to.”

The lack of structure in the women’s game meant the young players were immediately being thrown into the first team, with very little chance to develop their skills first.

“We would get some good, young, promising players, but we had no youth teams,” remembers Lopez. “Sometimes we’d take them on if we thought they could manage against us, at least in training, and then we’d give them a match when we played a weak team. It was difficult to accommodate the need.”

Lopez thinks that the FA’s failure to embrace the female game has created the serious problems that it still faces today. England are still playing catch-up with some of the countries that were early adopters of women’s football. The reluctance to acknowledge the obstacles faced by previous generations suggests that at some point the errors of the past may well be repeated. An over-reliance on the goodwill of volunteers, and a subtle condescension to the players that they are even permitted to compete at all, may lead to a breaking point.

“They didn’t want to help; they didn’t want to do anything,” says Lopez of the FA’s presence in her playing days. “It was just negative.”

That was different, however, when there was a showpiece occasion. Lopez and her Southampton team dominated the FA Cup for a decade after its creation in 1970/71, appearing in 10 of the first 11 finals and winning eight of them. Wherever the final was held – Bedford, Dulwich, Burton – there would be an interloper in attendance to shake hands and present the trophy. “We’d go to the cup final,” says Lopez, “and this top-notch bloke, whoever he was, would come along and present the trophy. We’d think, ‘Well, who are you?’”

The same thing happened at international level as well. Even though representative England teams had been competing for years, it was not until the FA lifted their ban that caps and goalscorers began to be acknowledged. Still, the England team did get to play on slightly better pitches, so as not to outrage the visiting dignitaries. As Lopez explains: “For an international match, some FA bod would turn up wearing his blazer, so it would have to look half-decent."

After paying her way through a series of trials, Sylvia Gore was picked for the first official England squad, and scored their first goal. Her strike helped England come from 2-0 down to beat Scotland in November 1972 – more than 50 years since the FA banned women from playing football; 55 years since Dick, Kerr’s Ladies began to tour the UK and the world as representatives of England; and nearly 80 years since the British Ladies’ Football Club was formed.

Lopez won 22 caps during her career, in a time when international matches were infrequent. They were difficult to arrange, there were few opponents and players were having to take time off work, before finding themselves out of pocket. “We were all very proud,” she says. “We thought we were getting a bit of acclaim for all our efforts.”

After Lopez retired from playing, she compiled a history of the game. Women on the Ball is still the most accessible and authoritative account of the way female footballers kept their own sport running for decades.

“I was proud of what we did, and also of the Women’s FA,” she says. “This was my way with dealing with my anger about how women had been treated in football. It was a hidden story, and it made me sick.”

Lopez even managed Southampton in the mid-2000s. Then she was made redundant when the men, relegated from the Premier League, stopped funding the women’s team.

Gail Newsham’s own footballing career was equally short of funding. She remembers one particular ground where the changing rooms were chicken huts with an oil drum to use as a toilet. “[The grounds] weren’t a lot to write home about – I don’t recall there being any hot water or anything like that,” she says. “It was pretty shocking, really. That really is playing for the love of the game.”

A love of the game was something Sylvia Gore never lost. She volunteered across the north-west, providing girls and young women with better opportunities to play than she’d ever had, and sat on countless committees governing local football. Manchester City Women invited her to become their club ambassador, acknowledging her work, and she had plans to be reunited with her old Manchester Corinthians team-mates. She organised the reunion for the end of the 2016 Women’s Super League season, in full expectation that City would be parading the championship trophy by then.

Gore did not live to see the Blues’ maiden WSL title win. After a short illness, she died in September 2016, aged 71. Her life and career were acknowledged with media attention and marked with a minute’s silence at matches.

“I would love the girls today to realise the effort involved,” reflects Lopez, who, like Gore, was awarded an MBE and inducted into the National Football Museum Hall of Fame for services to women’s football. “It’s not saying, ‘You’re lucky so-and-sos and we’re jealous’; it’s that there are loads of Sylvias who worked hard, and men – fathers, brothers, local people – who backed women’s football.”

Similarly, Newsham issues a stark warning of the dangers of forgetting history; sooner rather than later, the pioneers who kept the women’s game alive in the face of the FA’s instructions will all be gone. In 1993, the FA formally took control of the female game. Two decades later, during the Women’s European Championship, they celebrated “20 years of women’s football” – effectively erasing the century of history that they’d tried so hard to suppress.

This could well be the dawning of a second golden age for women’s football. All the more reason to be sure to remember the struggles of everyone involved in shaping the game – including that 12-year old girl from Prescot.

This article first appeared in the December 2016 issue of FourFourTwo

NOW READ...

Quiz! Can you name the Portugal and France line-ups from the Euro 2016 final?

8 football club owners who LOVE a good superstition

While you're here, why not take advantage of our brilliant subscribers' offer? Get the world's greatest football magazine for just £9.50 every quarter – the game's greatest stories and finest journalism direct to your door for less than a couple of pints. Cheers!

Order a copy, then subscribe! 3 issues for less than £10...