Wor Bella: forgotten story of women who combined war work with football

Much as followers of men’s football of a certain age and type sometimes struggle to comprehend the fact that the sport existed before Italia 90, recent aficionados of the women’s game can be rather blank about its history pre-Canada 2015.

Even those aware that women’s football was banned by England’s Football Association for 50 years until 1971 are often startled to learn that it thrived during and immediately after the first world war. And they will certainly have their eyes opened by Wor Bella, a play to be staged at Clapham’s The Bread & Roses Theatre and Newcastle’s Theatre Royal this month.

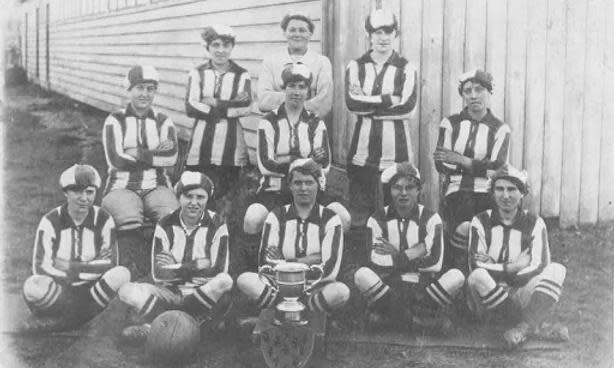

Ed Waugh’s play tells the story of a cohort of more than a million courageous young women who have been virtually airbrushed from history. The heroic first world war Munitionettes combined serving the war effort by working in munitions factories with playing football for charity.

Anyone who believes British women had barely kicked a ball before England’s Jill Scott, Lucy Bronze, Steph Houghton and company crossed the Atlantic and collected a bronze medal at the 2015 World Cup may be staggered to know that hundreds of Munitionette teams were formed nationally, including dozens in the north-east.

As fans began attending matches in their tens of thousands, female football superstars were born, perhaps most notably Bella Reay of Blyth Spartans Ladies. In scoring 133 goals in 30 matches – including a hat-trick in her team’s 1918 Munitionettes’ Cup final – the then 18-year-old “Wor Bella” possessed an eye for goal that Alan Shearer would have envied.

With matches at St James’ Park and Ayresome Park regularly attracting crowds of 18,000-25,000, Bella and co were part of a now near-forgotten sporting boom that would not be replicated for almost a century.

“Today’s Lionesses stand on the shoulders of those incredible women from 100 years ago,” says Waugh, who is from South Shields and has written a series of plays often highlighting little-known north-east-based working-class heroes. “The Munitionettes and their achievements are something that doesn’t seem to be taught in schools so we’re trying to keep their memory alive.”

Shearer has a cameo part in Wor Bella, playing a … Match of the Day pundit. “The story of the Munitionettes who worked 60 hours a week in dangerous and physically demanding conditions and still found time to play football for wartime charities is both incredible and inspirational,” says the former Newcastle and England centre-forward.

It is a message endorsed by Dan Burn. The Blyth born-and-bred Newcastle defender has received more than 36,000 social media hits after promoting the Theatre Royal production by urging Tynesiders to buy tickets via a short “Howay the Lasses” video address.

Bella is played by the Vera actor Catherine Dryden and she skilfully transports the audience back to 1916 when Blyth’s working age male population departed the Northumberland town en masse to fight at the Battle of the Somme and Ypres.

As the Munitionettes laboured as stevedores, loading munitions headed for the front and unloading spent cartridges on and off ships moored at Blyth docks, they began receiving informal harbour-side coaching from visiting sailors. By 1917 Blyth Spartans Ladies were alive, kicking and increasingly formidable.

Not that this is purely a play for football aficionados. “Before the war around 50% of young, unmarried, working-class women in the north-east went into badly-paid domestic service,” says Waugh. “But once they were drafted into the factories, they suddenly had money in their pockets. For the first time, young women went into bars unaccompanied and they would quite often drink them dry. There are stories of the remaining men arriving only to find the booze had run out.

“Wor Bella is about a time of revolutionary social change when, for the first time, a cohort of young working-class women had money and freedom. They could afford to have their hair cut fashionably short and play what had always been a man’s game.”

By 1921, the men had returned to factory work but women’s teams continued to attract huge crowds. A tipping point was reached in the north-west on Boxing Day 1920 when 53,000 fans – with a further 15,000 locked out – packed Goodison Park to watch the famous Dick, Kerr Ladies against St Helens.

December 1921 duly saw the FA bar women from playing on affiliated pitches on the spurious “medical” grounds that the game was “unsuitable for women”. The ban not only forced female football underground for five decades but helped reimpose socially conservative ideas about women’s place in wider society. “There are some very funny moments in Wor Bella but it’s not all laughter, it should also make people angry,” said Waugh. “Really angry.”

Dryden describes the 1921 FA ban as “scandalous” and is delighted to be bringing Bella, who died from dementia in 1979, back to life. “The play is a tribute to the million-plus women who stepped into exhausting and dangerous industrial work when men were conscripted in 1916,” she says. “Apart from serving the war effort, they raised money to support injured soldiers, widows, and orphans. They were selfless.”

Wor Bella is at The Bread & Roses theatre in Clapham, south London, from 22-24 April and the Theatre Royal in Newcastle upon Tyne from 27-28 April

Get in touch

If you have any questions or comments about any of our newsletters please email moving.goalposts@theguardian.com. And a reminder that Moving the Goalposts runs twice-weekly, each Tuesday and Thursday.

This is an extract from our free weekly email, Moving the Goalposts. To get the full edition visit this page and follow the instructions.