Philippa York: You’re not a normal person to be able to cope with these bike races

“You’re not a normal person. You just can’t be, because a normal person wouldn’t be able to cope with what you go through in these bike races.

“The stimulation you get in professional bike racing is different from anything else on the planet and if you’re able to thrive in those situations, you’re really not normal.”

Philippa York’s description of herself, and those like her who choose to put themselves through hell riding up and down near vertical mountains in the pursuit of glory, cannot be disputed.

But it’s this absence of a “normal” person’s mindset that made York such an exceptional athlete.

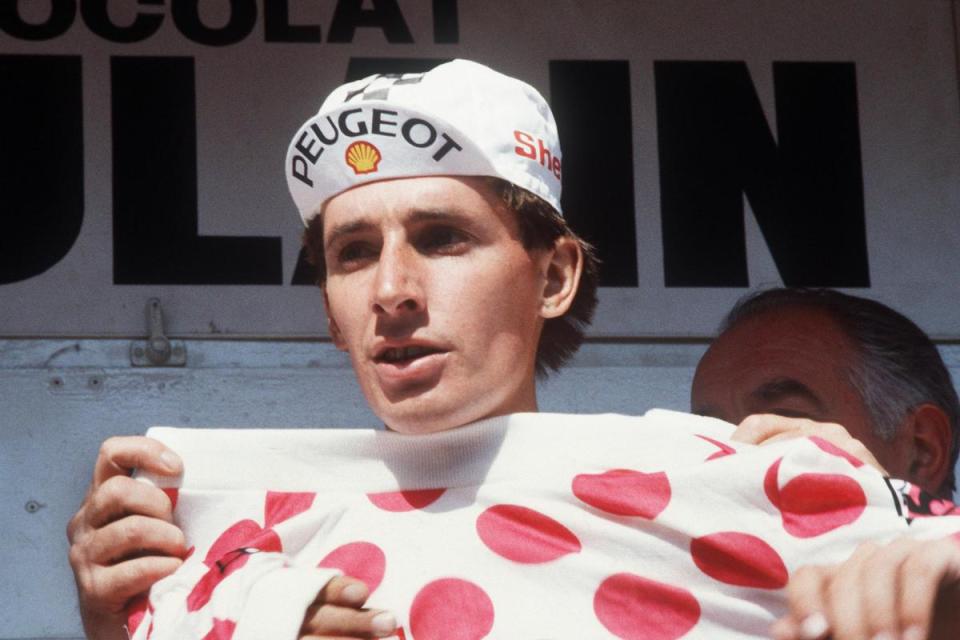

This summer is the fortieth anniversary of York’s greatest achievement on a bike, and one of the greatest achievements in Scottish sporting history.

Philippa York, who raced as Robert Millar

At the 1984 Tour de France, York, who was then known as Robert Millar, won the mountains classification, becoming the first British rider ever to claim the overall polka dot jersey.

She remained Britain’s most successful cyclist in the world’s most famous bike race for almost three decades, until Bradley Wiggins was crowned champion in 2012.

To describe York as a trailblazer in her day would be something of an understatement.

Born in the Gorbals in Glasgow in 1958, York was not, unsurprisingly, surrounded by cyclists.

But having discovered she had a talent for bike racing, she quickly realised that cycling may be her route to a better life.

“When you come from a poorer background, like most of Glasgow used to be, there’s only a couple of ways out of that and usually it meant that you left Glasgow,” says York, who now lives on the English south coast.

“Back then, it was unique to dream about being a professional cyclist. My parents didn’t discourage me but becoming a pro cyclist was a step not many people could see themselves doing.

“But aged about 16, I realised becoming a pro cyclist was a thing and I thought well, it has to be better than working in a factory so I looked at the steps I’d need to take to make it happen.”

By the time York made the decision to move to mainland Europe in 1979 – she relocated to France – she was already Scottish junior champion and Scottish senior hill-climb champion, as well as having established herself on the British scene.

The move to France was, however, a shock to the system.

“The winter before I moved, I learned to speak French from courses on cassette tapes,” the 65-year-old recalls.

“France was very different from what I’d come from. It wasn’t better or worse, it was just a different lifestyle.

“If you didn’t fit into their world, they rejected you and cycling-wise, you start at the bottom of the hierarchy.

“At first, I did think wow, this is hard but I loved it – even if I’d not progressed any further, I was getting paid to go out cycling so what could be better than that?”

In York’s early days as a professional, she had no aspirations of becoming one of the best in the world.

She entered professional cycling at a time where one of the sport’s all-time greats, namely Bernard Hinault, was dominating, and just as two more – Greg LeMond and Laurent Fignon - were beginning to emerge.

But it quickly became apparent that York had what was required to make it in a sport that’s as physically demanding as any.

In her opening seasons as a pro, York, racing as Millar, claimed several notable results but it was her debut Tour de France, in 1983 when racing for the Peugeot team, in which she really came to the wider public’s attention.

York was one of the world's very best pro riders in the 1980s

In the Pyrenees, York took her first Tour stage win before ultimately finishing third overall in the mountains classification.

It was a result that was to set her up perfectly for her mountains triumph the following year.

“Winning that stage in ‘83, I felt relief. And then it gives you a level of confidence, especially when you realise not many people from Britain had ever won stages at the Tour de France, so I did think I wouldn’t mind doing that again,” she says.

“As soon as the ’83 Tour finished, I started planning what I was going to do that winter with a view to winning the mountains classification the following year.

“My training stepped-up another level and I looked at everything I needed to improve upon to deal with what was to come.

Mentally, I worked on my weaknesses. In certain situations, my emotions would come into play and you don’t need any emotions in bike racing.

“In ’84, I wasn’t team leader but I was second in command.

“Throughout the race, some days you’re good and some days, you’re not so good. But you get used to a certain level of pain and fatigue.

“To win the mountains classification was, again, a relief. It’s 12 months of work that’s gone into it.

“But you don’t actually get to enjoy it at the time because almost straight away, you move onto the next thing. You think about doing it again and also about whether you’re good enough to step up yet another level to being one of the people who can win a Tour de France.”

It’s almost impossible to put oneself in the saddle of these riders.

The conditions riders endure during cycling’s grand tours, and particularly during mountainous stages, are unlike anything else in the sporting world.

The inclines are often treacherous, and the fans are mere centimetres from the athletes’ faces.

York can vividly recall much of what she went through on these stages, but not all.

“It’s a long time ago – it’s forty years since that ’84 Tour. There’s just too many races and stages to remember everything,” she says.

“On a mountain stage, it’s really, really noisy – people are screaming in your face, there’s helicopters above and your head’s thumping. While you accept that’s your working conditions, it does wear you out and afterwards, you want to just lie on your bed and process what’s happened that day.”

York’s achievement on her bike was distinct, and so was her personality.

She was often described as brusque with the media, and sometimes flat-out rude.

But she had a mentality that was years ahead of her time.

Team Sky may have popularised the term “marginal gains”, but York was training that way decades before Sir Dave Brailsford coined the phrase.

And so, with such dedication to her cause, it’s hardly surprising that York had little time for much of the rigmarole that often surrounded the top riders.

“You get used to being in the public eye but in the 1980s, it was guys like John McEnroe who were the role models and you look at how they dealt with someone asking a shi*ty question and they’d tell them to eff off. That becomes your template.

“Every minute I was spending doing other commitments was time I wasn’t doing my recovery. And my role wasn’t to be nice to people, it was to produce a result.

“Everything is focused on the outcome so things like being emotional, pleasant and having empathy just don’t exist. Your ego and desires are very different to normal people and that’s what allows you to have the ability to go into that competition sphere and have that drive.

“I once spent a year improving my flexibility so that, when I fell off, I would hurt myself less. I figured that if I was more flexible and I fell off and bounced down the road, it’d hurt but not as much as it would have if I’d had less flexibility. That was the level of madness I had.”

York was contending with something her fellow riders were not, though.

Having first recognised she was “different” at the age of around five, York spent her racing career battling gender dysphoria.

To everyone else, she was male but that’s not how York felt. And so, despite her incredible success on her bike, York was emotionally in turmoil.

“Internally, I was a mess. A complete mess. I wondered if I was crazy because then, I had no contact with other people like me. I thought there must be something wrong with me and there’s a whole load of mental stress that comes with that,” she says.

“Some seasons, I’d be ok and I’d go the whole year with no dysphoria and other years, it’d be bad. So then, I’d have to completely turn off my whole emotional system.

“That level of focus you need as a rider definitely helps you shut other things out.”

York recorded several other notable results following her polka dot jersey win in 1984 including a brace of second-places in the Vuelta a España in 1985 and 1986 and second in the 1987 Giro d'Italia, as well as winning the climber’s green jersey that year.

York retired from professional cycling in the mid-1990s and dabbled in coaching but she then disappeared from public view, only re-emerging in 2017 having transitioned from male to female.

It’s been quite a journey, and the fact that York’s exploits at the Tour de France four decades ago remains one of this country’s great sporting feats says much about her achievement.

When asked for a summary of her career, she sounds satisfied more than anything. But she’s in no doubt that, as a person, she’s much more contented these days than she ever was as a bike racer.

“I probably am happy with my career as a whole. Could I have done certain things better? Yes. But overall, I didn’t do too badly,” she says.

“I’m much happier now that I’ve transitioned, though.

“If I watch replays of myself racing back then– do I recognise that person? Vaguely.

“But I still ride my bike, although not very fast and not very far. I go round hills instead of up them now. I’m happy with that, though."

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport