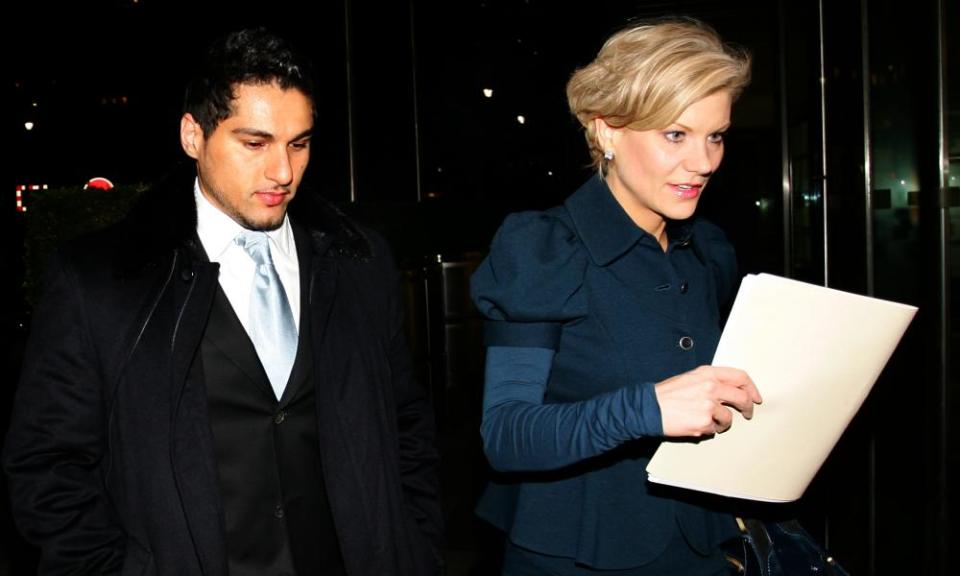

Amanda Staveley: the unusual case of Newcastle United’s would-be-owner

For supporters of Newcastle United, the great, underperforming north-east football institution, the indignities of ownership under Mike Ashley have ground up the gears again. Ashley, boss of cut-price retailer Sports Direct, broke months of silence following his decision in October to advertise the club for sale by this week authorising a statement denying there is any “deal on the table” from the businesswoman Amanda Staveley or that there are any current discussions with her.

Staveley, who has adopted a very public interest in buying the club, maintains that she has an offer “on the table” of £250m, £100m short of the minimum Ashley wants. It is not clear why Ashley would be expected to accept less even than the £263m he has spent on Newcastle, which he has made financially stable, in a vastly more lucrative Premier League than when he took over in 2007.

Supporters encouraged to believe in a Staveley takeover as the only salvation from Ashley are entitled to know much more about her and her businesses, rather than the general impression of connectedness and mega-wealth which customarily travels with her.

Staveley’s reputation derives principally from two deals she was involved in with the same investor, Sheikh Mansour of Abu Dhabi, both completed in quick succession almost 10 years ago. She is said by sources close to her to have £28bn under management – an extraordinary sum – including wealthy investors in the Middle East, Far East and the US, and countries’ sovereign wealth funds. It has been suggested that Newcastle may be too small a deal for such investors and that Staveley might pay for the club mostly out of her own wealth.

Given this portrayal, it is striking that PCP Capital Partners LLP, Staveley’s UK-registered company, has no assets or employees. It qualifies for official Companies House filings as a “micro entity”, having had no income in the year to 31 March 2017, and debts of £3.6m. The accounts for the year to 31 March 2009, covering the period of the two deals with Mansour, are barely more substantial.

The assumption has always been that Staveley must have a very substantial operation in Dubai or elsewhere, although there are no other public filings of financial information. Sources close to her have said she does have operations in other countries but is not required to publish accounts there.

Staveley did not do standard financial training; she is described as self-taught in corporate finance, after meeting wealthy men from the Gulf when she ran a restaurant near Newmarket, where their racehorses ran. She did play a role in Mansour’s acquisition of Manchester City, working with his advisers and connecting them with the seller, the former Thai prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

Staveley also introduced Mansour and his advisers to his £3.5bn investment in Barclays Bank during the financial crisis, from which the sheikh ultimately reaped a fortune in profit. Mansour paid Staveley a £30m fee for that work, which she has said was paid to her Jersey-registered company, and she revisited this 2008 deal two years ago, when she launched a lawsuit against Barclays. Her claim is that Mansour had initially agreed to give PCP Capital Partners 10% of his investment for free and that PCP would then have made a profit by selling it, amounting to £721m. She claims that this 10% share was not ultimately forthcoming because of the structure of the deal, which she alleges she agreed to based on false statements from Barclays executives.

This huge legal action has been brought not by another major financial entity of Staveley’s but by PCP Capital Partners LLP, her tiny, UK-registered company. It describes itself in the claim as: “A private-equity firm set up for the purpose of making investments both on its own behalf and on behalf of investors on a transaction-by-transaction basis.”

Barclays, in its defence document setting out the bank’s vehement rebuttal of the claims, does not even accept that description, citing the Companies House record and dismissing PCP Capital Partners as “a company of no substance whatsoever”.

Its defence document rejects the idea PCP was a potential investor in Barclays, describes Staveley’s claim that Mansour was going to give her 10% as “embarrassing for want of particularity [detail]” and challenges her to prove it in court.

She first signalled interest in Newcastle when she turned up at St James’ Park in October for the match against Liverpool, apparently on the invitation of Rafael Benítez, who was the Liverpool manager in 2008 during one of Staveley’s two efforts to buy that club, neither of which completed.

Asked by the Guardian for more information about her business and the funding of the Newcastle offer, her representative said she was too preoccupied with other deals to respond in detail at short notice. She did, though, authorise the naming of one Newcastle co-investor, the rich list-topping property billionaires, the Reuben family. The Reubens do not have funds under Staveley’s management; they said she approached them in November, after she had publicly made known her interest in Newcastle. Although a son, Jamie Reuben, did then quickly agree financial terms to support her, the account of his uncle Simon, one of the billionaire Reuben brothers alongside Jamie’s father David, is that the family looked at the proposition but, following the rejection of Staveley’s bid, are emphatically not investing.

The identity of Staveley’s other partners and make-up of the £250m bid have not been revealed. What happens next, as the saying goes, remains to be seen.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport