Bob Knight: 'He never really let the world see the good side.' But it was there.

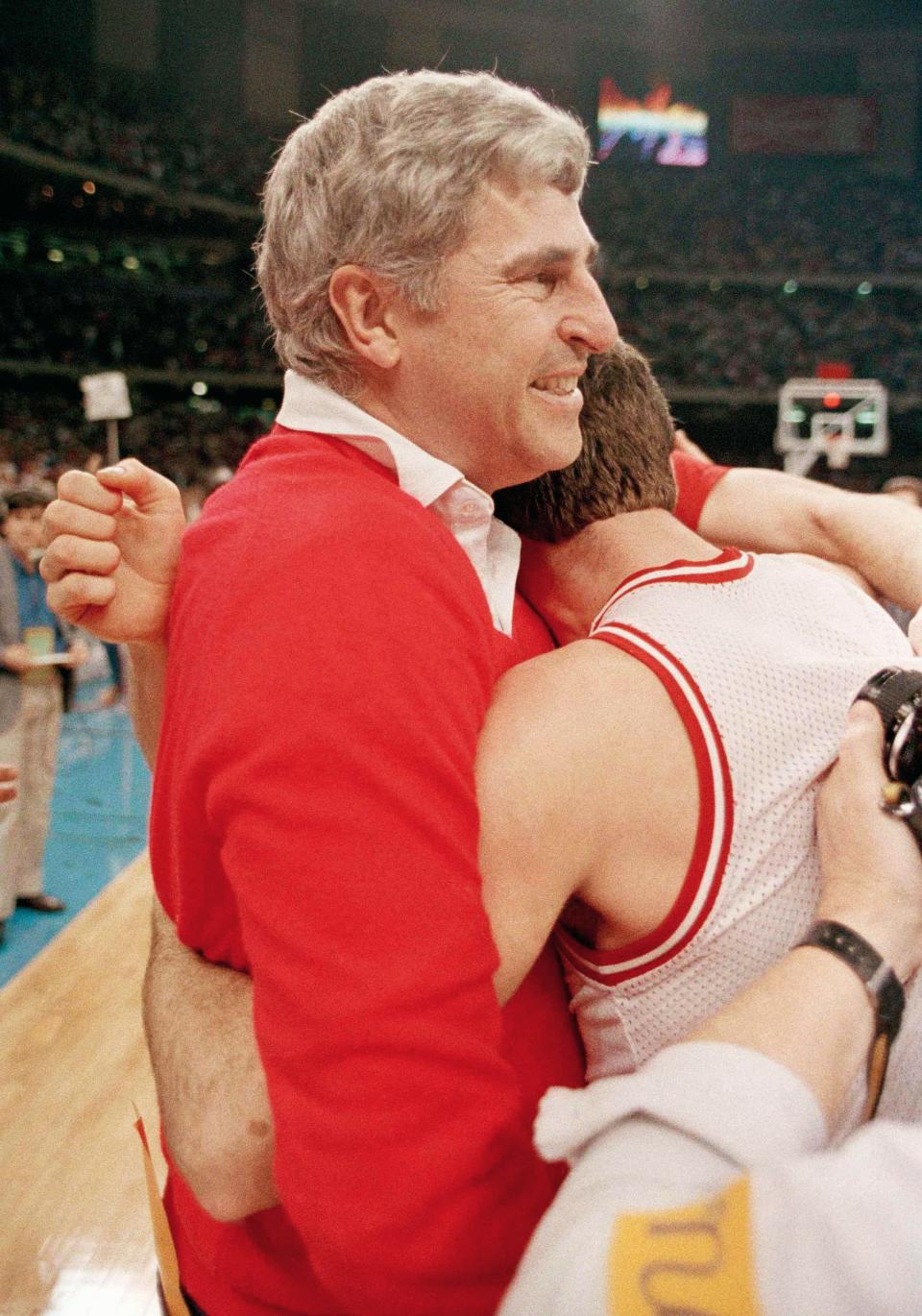

BLOOMINGTON − As Bob Knight became softer in his old age, his memory sometimes failing, the twilight years looming and the good old days of Indiana University basketball far behind him, he started doing unthinkable things. He started saying unrecognizable things.

They were things that didn't match the fierce, raucous, cursing, red-sweater-wearing IU coach the college basketball world was used to.

Knight went from a looming, fiery, seemingly cold-hearted, sometimes out-of-control personality who threw chairs, mocked reporters, and made players uncomfortable, to an elderly, still towering, feeble figure who would stand up in front of crowds and endear them.

He would make those fans laugh, then he would make them cry. Knight cried, too.

In the final years of his life, Knight made countless public appearances. From high school gyms to local bars to political conventions to retirement homes to packed speeches in stadiums, Knight would show up and, inevitably, tears would fall.

Knight would talk about all his kids, the players he coached, and how he always wanted the best for them. How he wanted them to get a good education and to be good men who got good jobs and made a difference in the world. And Knight would cry.

He would talk about Landon Turner who, in 1981, the summer between his junior and senior seasons playing for IU, was paralyzed in a car crash. It ended his college career and his future in the NBA. Knight talked about how unfair that was, how Turner had so much greatness ahead of him. And he would cry.

Knight would talk about his relationship with former Purdue coach Gene Keady which, through the years on the court, had been contentious, but in later years had mellowed into a wonderful friendship. And he would cry.

Knight made his return to Assembly Hall for an IU basketball game in February 2020, surrounded by dozens of former players, and he cried. He showed up to Bloomington bars, making impromptu speeches, and he cried.

But as Knight took the stage in front of a crowd of more than 500 inside Center Grove High School in April 2019 for an appearance called "An Evening with Bob Knight," he became as emotional publicly as he ever had.

Through tears, Knight looked up at all those fans, barely able to get the words he wanted to say to come out. "The best days of my life," he said, "were when I was at IU, coaching for you guys."

The crowd rose to their feet, and they cheered. The standing ovation was more about the emotions Knight showed them that night than it was for any championship-winning team he had coached at IU.

Those fans that night saw a side of Knight they didn't know existed, a side that was sweet, humble and, until then, unimaginable.

But that crowd had no idea. This soft side of Knight had been there all along, for decades, as he swore at referees and taunted reporters. He just hid it from the public.

Through the years, Knight did countless, selfless, giving things behind the scenes, but he never wanted publicity. He gave millions of dollars of his own money to help causes of diversity and education. He visited dying fans and helped struggling college students and professors find their way.

He changed the way high school basketball coaches ran defense and drew up plays. He gave teachers inspiration with his focus on academics. He became an idol to diehard fans. He became a revered symbol to men and women of what passion, hard work and grit could produce.

In 29 years with IU, from 1971 to 2000, Knight led the program to a 662-239 record, made 24 NCAA tournament appearances and won titles in 1976, 1981 and 1987.

As the world looks back on Knight, who died Wednesday at the age of 83 as, arguably, one of the greatest college basketball coaches to ever take the helm of a team, they will remember Knight's impact on the court.

But few will remember, or even know about, or even stop to think about the immeasurable impact Knight had off the court, which was widespread and rippled throughout the entire state.

That side of Knight has been overshadowed by his winning record, by his controversial coaching style and by his domineering presence which seemed, at times, ruthless.

"But people should know. There was also a side to him that was so kind and generous," said former Indiana Governor Evan Bayh. "But for some reason, he never really let the world see it."

Bayh was lucky enough to see it firsthand.

'He cared deeply about our youth'

It was 1989 and Bayh had been in office just two weeks as governor of Indiana when his receptionist walked in to tell him he had a visitor. That visitor's name was Bob Knight and he was adamant he needed to talk with Gov. Bayh.

"I said, 'Wow, OK, sure, show him in,'" Bayh said. Knight walked into the governor's Indiana Statehouse office. The coach wasn't really smiling, but he didn't look mad, either.

Bayh had no idea why Knight was there. At first, they exchanged pleasantries, Knight congratulating Bayh on his new office, and Bayh telling Knight how he was a 1978 IU graduate from the era when Knight coached his teams to two seasons that included only one loss. Knight smiled.

Then Knight got down to business. He needed Bayh's help. "You see governor? We've got a problem with drug use by too many kids in our state."

Bayh agreed, encouraging Knight to go on. "Frankly they won't listen to me, and they won't listen to you," Knight said. "But they adore basketball players."

Knight was incredibly worried about drug use among Indiana youth, authentically worried, Bayh said. It kept him up at night. He cared deeply and he desperately wanted to do something about it.

Inside Bayh's office that day, Knight told the governor he had produced a video, getting NBA stars Larry Bird, Magic Johnson, Michael Jordan, Isiah Thomas and Kevin McHale to look straight into the camera and tell kids why they shouldn't do drugs, why they were bad, how they wouldn't succeed in life if they turned to drugs.

Knight had used his own money to produce that video and to make thousands and thousands of copies. He offered those videos to Bayh, pleading with him to make sure they were shown in middle schools throughout the state.

Of course, Bayh was all in. But that interaction with Knight left him with a newfound respect for this IU coach, one that had nothing to do with basketball.

"He just did that because he cared about our youth," said Bayh. "He never got any publicity for that. And he didn't want any publicity for that."

'He really inspired us as teachers'

Before Debbie Muterspaugh was a young, up-and-coming teacher in the 1970s who admired the academic discipline Knight instilled in his players at IU, she was a little girl who watched IU basketball.

Her mother, Vera Sackett, born in 1912, was a diehard IU fan and, in her 60s, 70s and 80s, she became a diehard Knight fan.

"You never talked to her when Bob Knight was playing," Muterspaugh said at her mother's funeral in 2005, "because she didn't want to be bothered during the game."

Growing up, Muterspaugh was well aware of Knight's basketball prowess on the court. But after graduating from Lawrence Central High, getting her teaching degree and becoming a first-grade teacher at Indianapolis Public Schools, Muterspaugh was inspired by Knight's focus off the court.

As she taught children at inner city schools, Muterspaugh watched Knight give his own money to libraries and causes that helped urban youth. She watched as he insisted that all his players study hard and graduate.

"As an educator, I thought that was wonderful," Muterspaugh said. "He really inspired us as teachers."

A lot of people focused on negative things Knight did. Muterspaugh always focused on the positives, and she is sure he didn't just inspire her but countless teachers throughout the state.

"He was Bobby Knight, an icon at the time, a hero, I mean he was Bobby Knight," said Muterspaugh. "And he was out there telling the world how important education was."

High school basketball coaches 'idolized him'

Knight would open his practices at IU, which were off limits to the public, to Indiana high school basketball coaches. And, for nearly three decades, those coaches would descend on the Bloomington campus, soaking in everything they could from Knight, designing their plays around what they watched him do.

"I think most of the coaches that started out in the 1970s and 1980s idolized him," said Jimmie Howell, an Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame coach, who attended Knight's practices.

As Knight coached at IU, Howell coached high school -- Mt. Vernon, Muncie South, Brownsburg and Lapel -- and he watched the game change.

"The reason high school teams today have all the motion offense is because of what Knight instilled when he started at IU," Howell said.

And as Knight played hard man-to-man defense, high school coaches did too, even as zone defenses were prevalent at the time.

"Him playing man-to-man showed it could be done, the ball movement they had when he was coaching, the screening," Howell said. "He had a lot to do with setting screens for players, especially off-ball screens for shooters."

High school coaches started using role players, because Knight did, players who probably weren't going to score, but were good rebounders or fierce defenders.

The high school coaches admired how Knight's teams were so disciplined. "A lot of coaches wanted their kids to do this. They tried to get their kids to do this," Howell said. "Knight demanded they do it."

And that gained respect, not just from high school coaches, but from fans, said Howell. "I think a majority of IU fans became IU fans because of Bob Knight."

'People didn't see the good side as often as the bad side'

Jim Sherman will never forget the day his unlikely friendship with Knight was born. It was the mid-1980s and Sherman was a renowned psychology scholar and professor at IU's department of psychological and brain sciences. He was sitting in his office on the phone when the administrative assistant burst through the doors.

"You better get off that phone right away," she told Sherman. "Coach Knight is on the phone and he wants to talk to you now."

Knight had called to thank Sherman personally for a letter he had written to the coach. The letter came after Sherman was interviewed by a newspaper reporter for an article. When the article came out, Sherman was astounded at how biased the reporter had been.

Coach Knight, I understand now why you are so wary and leery of the press, Sherman wrote in his letter. Knight absolutely loved that. He had never liked the press and he wasn't shy about making that known.

On the phone in Sherman's office that day, he and Knight commiserated about the media and talked a little basketball. As they hung up, Knight told Sherman he was welcome to come to practice, any practice, any time.

Sherman went to those practices, a lot, where he sat in the bleachers and absorbed everything Knight did, everything he was and was not. Knight would come over and talk to Sherman and the two became friends.

Through the years, Sherman was interviewed by the media as a psychiatrist who was also a friend of Knight's. People often asked Sherman if Knight was misunderstood.

"I don't think he was misunderstood. I think he was what he was, and he wore it proudly," Sherman said. "You either accepted what he was, or you didn't. He would be cruel, he could be not empathetic, he could erupt and that's who he was.

"So, if he was misunderstood, it was that a lot of people didn't see the kindness or thoughtfulness. People didn't see the good side of him as often as they saw the bad side of him."

Sherman always admired Knight for the way he did his job honestly. In 29 years of coaching at IU, Knight had only one serious NCAA violation, that one incident with Steve Alford.

In late 1985, Alford posed for a Gamma Phi Beta sorority calendar that was sold to raise money for charity. He was photographed in a sports coat, a button-down shirt open at the top and blue jeans. Even though Alford didn't make a cent on the photo, it was still an NCAA violation, and he was suspended for a game.

That incident got a lot of publicity, as did Knight's tirades on and off the court, but the nice things Knight did behind the scenes never did, the things he did for players and the university. "They never got any notice," said Sherman. And that's the way Knight wanted it.

As he coached at IU, Knight set up a fund for the university library. He donated plenty of his own money and rallied other people to donate. When IU was trying to build a minority student activity center, Knight wrote a personal check for $250,000, after other funding fell through.

Knight took time to talk to students and professors. He genuinely cared about their lives, Sherman said. Knight was a mentor to him as he navigated his career, as he got job offers from other universities.

"More than anyone else, he talked to me and gave me good advice on whether I should go," said Sherman. "He was very generous with his time, not to everyone, not to the media and not to people he didn't know. But he was very kind and generous to people that he knew and trusted."

'He was your biggest advocate'

When Knight was fired as IU's coach in September 2000, he turned to Andy Murphy, who was an IU basketball student manager the final four seasons of Knight's career.

Knight needed to clean out his office in Bloomington and he called Murphy to help. Murphy found himself standing in Knight's office with an Olympic gold medal in one hand and three national championship rings in the other.

"It was awesome," Murphy, who suffers from ALS, said in 2021, of being on a team with a coaching legend. "Knight was demanding and hard on you but if you were loyal to him and worked, he was your biggest advocate."

Murphy found that out when he went through one of the hardest times of his life.

After graduating from IU, Murphy received a job offer with the Orlando Magic as a video coordinator. It was a basketball lover's dream job. Before starting that job, he went to Cincinnati for a guys' trip with his brother and a couple friends. One night, walking back to the hotel, four men with baseball bats came out of an alley and beat and mugged Murphy.

They took one of his shoes and his IU commemorative watch he'd gotten as part of Knight's team. Murphy woke up in the hospital, after being found by police in a pool of blood. He had suffered a traumatic brain injury. Doctors advised Murphy not to take the Orlando job. It was too high stress, too many hours and he needed to recover.

During that time, Knight was there for Murphy. He replaced the watch and helped him land another dream job, this time at Ohio State.

Murphy had no idea what Knight had done until he was driving to Denison University in Ohio where he had been offered a job. It was not really the job he wanted, but he didn't have anything else. As Murphy drove to Denison to accept the offer, he found out Ohio State was looking at him for a position.

He then found out that was all because of Knight. Knight hadn't told Murphy what he had done. But when Ohio State reached out and the person on the other end called him "Murph," he knew. That's what Knight called him. Knight had pulled some strings for Murphy.

Knight was always doing things for others, said Bayh. And yet, no matter how loud the naysayers became, he never wanted people to know.

"He was very generous, very philanthropic and he cared deeply," said Bayh. "Yes, there was a side to the coach, even his friends will realize and say, 'There was a little bit of a cantankerous side to him that didn't always work in his favor.'

"But there was a softer side to him that was there all along."

Follow IndyStar sports reporter Dana Benbow on Twitter: @DanaBenbow. Reach her via email: dbenbow@indystar.com.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: IU basketball Bobby Knight's positive impact widely unknown

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport