How a Chinese art teacher inspired a new generation of protesters

The scenes at the iPhone factory in central China were unbelievable. Angry workers setting gates on fire, Covid testing booths being smashed and clashes with riot police.

Videos of the scenes last month at the Foxconn factory in Zhengzhou were popping up on Kuaishou, a short-video platform popular among working-class Chinese but they were quickly being scrubbed out by China’s censorship machine.

From his home in Italy, Li watched the videos in amazement - and decided to do something.

The 30-year-old Chinese art teacher, who asked that his full name not be revealed to protect his identity, saved as many as he could and uploaded them to Twitter, where the world could see them and they would be beyond the reach of Beijing’s censors.

Before long, news that protests against China’s draconian zero-Covid policies were bubbling up had spread around the world, and Li had unexpectedly thrust himself right into the heart of a wave of unrest that would sweep the country in the weeks to come.

上海乌鲁木齐路 最新视频

警察开始围堵,民众大声质问警察 pic.twitter.com/KbYucQEJCW— 李老师不是你老师 (@whyyoutouzhele) November 26, 2022

Posting from his Twitter account called “Teacher Li is not your teacher,” the videos he has shared have been seen more than one billion times in the last month. Although Twitter is banned in China, those with a VPN can still access it.

With almost no foreign or independent journalists left in China, he has played a central role in chronicling and raising awareness of recent events there, from the Foxconn factory riots to demonstrations in Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi to mass protests across university campuses and major cities such as Beijing and Shanghai.

With some protesters even demanding that Xi Jinping, the Chinese president, step down, it amounts to the largest wave of civil disobedience China has seen since the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989.

“I was the person chosen by history to blow this horn,” Li told The Telegraph in an interview. “I was pushed into this position; I had no choice but to continue.”

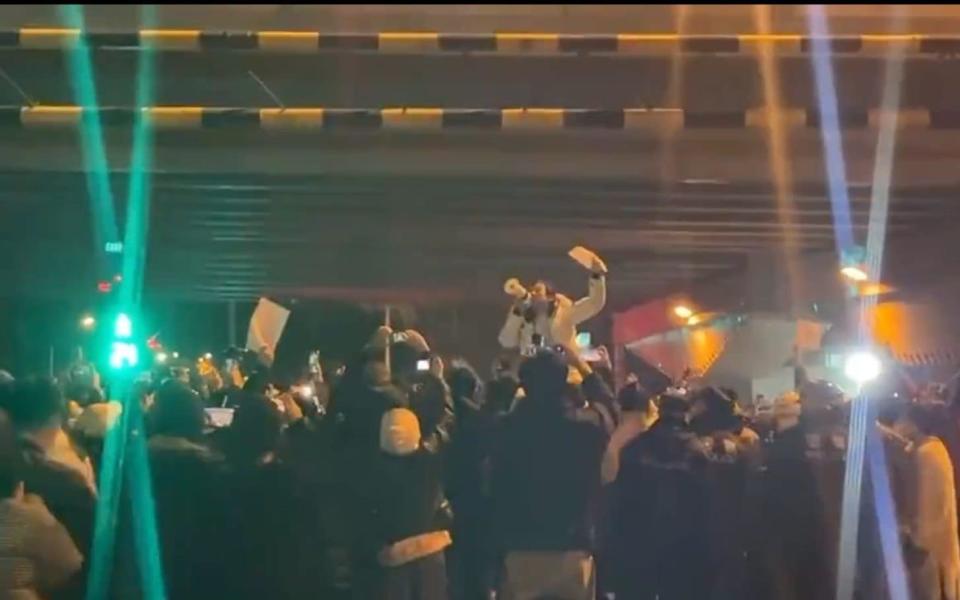

亮马桥 此刻

一白衣男子发表演讲 pic.twitter.com/51eGHjOxEm— 李老师不是你老师 (@whyyoutouzhele) November 27, 2022

Li grew up in China’s mountainous Anhui province, part of a family that had been labelled as “counter-revolutionaries” and persecuted under Mao Zedong.

His parents instilled different values in him than the hyper-nationalist education he received at school. They also encouraged him to travel abroad.

In his early 20s, he visited France and while in a hotel one night, he watched a three-hour long documentary about the Tiananmen Square protests and the resulting massacre, a banned subject in China.

“I was totally changed,” he said.

Since then he has continued to travel. He went to Italy several years ago to study art and got stuck there during Covid.

For years he used Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, to share the truth of what is happening in his country and vent about his frustrations, invariably being suspended every time he posted something the authorities did not like.

“I would open a new Weibo account every time I got suspended as a way to resist the control of freedom of speech,” he said.

But when his account was shuttered for the 52nd time this May after he wrote about social injustice cases and women’s rights, including a woman found chained in a hut earlier this year, he decided to switch to a different platform: Twitter.

武汉,民众走到哪拆到哪 pic.twitter.com/GuUMBLK6Lu

— 李老师不是你老师 (@whyyoutouzhele) November 27, 2022

Things only really started picking up last month when he shared footage from inside the Foxconn factory, footage that would otherwise have been scrubbed by Beijing.

Before long, he was being flooded with direct messages from people across China, sharing fresh footage they had seen on local social media networks. Some Twitter users even volunteered as “citizen journalists” to obtain first-hand videos to send to him to publish.

“During the [peak] period, I would receive dozens of submissions per second,” Li said.

At first, he tried his best to verify them, but he later decided it was more important to post as many videos as possible online so they could be archived on Twitter, away from the Chinese censors’ reach.

It did not take long for Chinese authorities to notice his new tactic. First it was just vague threats online. But this week, he heard that his parents back in China had received a visit from the police. He knows his work could land him or his family in jail - or leave him exiled for good.

上海乌鲁木齐路 民众高喊

共产党 下台!

这是迄今为止最为激进的口号。 pic.twitter.com/ijP7lxnIgH— 李老师不是你老师 (@whyyoutouzhele) November 26, 2022

“If I am never able to see my family again, indeed the price is very, very high,” he said. “I don’t really know if it’s worth it because I’m not in a mood to ponder that. I didn’t realise what I was doing at the time. Everything happened so fast.”

He said he became emotional watching protesters in Shanghai last weekend calling for Mr Xi and the ruling Communist Party to step down.

“People didn’t become more radical; it was the elephant in the room that grew too big,” he said. “The things most people ask for are not too much. They only ask to have a normal life.”

Many cities across the country have now started to lift some Covid restrictions, though the process is uneven and may take a long time. He is realistic about how much will really change in Beijing.

“In any case, we will remember that in these few days, some brave people stood up,” he said.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport