Cricket must make bold climate choices in post-Covid world

Last Sunday, Steve Smith fidgeted to his second successive 62-ball century against India. The night before, Sydney broiled in its warmest November night (25.4 degrees at 1am), while Smithville recorded New South Wales’s hottest November temperature as the mercury hit 46.5 degrees. In rural New South Wales, bushfires are already burning and less than half of Australia’s expected rainfall for the month has fallen. Yet, officially, the Australian summer started only on 1 December.

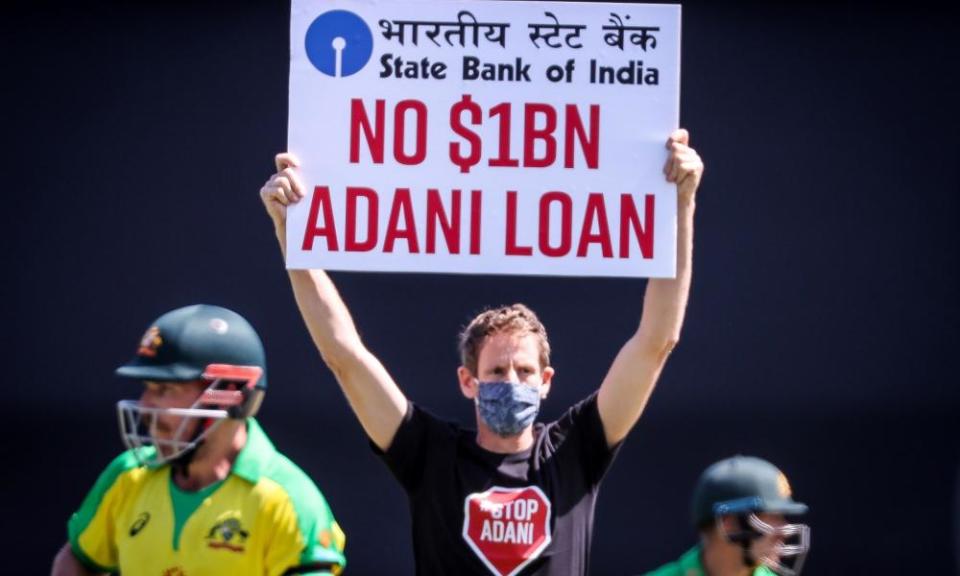

The terrible bushfire season of 2019-2020 killed or displaced three billion animals, killed 33 people, destroyed more than 3,000 homes and scorched 11.46m hectares of land as well as disrupting recreational cricket across the country and causing the cancellation of a Big Bash game in Canberra because of heavy smoke. But when two climate protesters ran on to the pitch at the SCG during the first one-day international against India, they weren’t just raising the profile of the climate crisis in Australia. They were also trying to raise awareness in India, where the State Bank of India is reported to be close to finalising a $1bn loan for Adani’s controversial coal project in Queensland. A loan would allow the company, finally, to dig the mine and build the railway to open up the Galilee Basin, one of the largest unexploited coal reserves in the world.

Related: The Spin | Gone in 11 seconds: how technology fixed cricket fixture headaches

The project has been tagged “the most insane energy project on the planet” by Rolling Stone magazine and “an act of climate vandalism that represents everything that has gone wrong with politics in the civilised world.” It threatens the survival of the Great Barrier Reef as well as releasing what climate groups estimate to be 4.6bn tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere. India, where most of the coal will be heading, is one of the most climate-vulnerable countries in the world and suffers from debilitating levels of air pollution in major cities, something that brought play to a temporary halt during a Delhi Test against Sri Lanka in 2017. The traditional owners of the land where the mine will be dug, the Wangan and Jagalingou people, have also protested that the project would cause chaos to their way of life.

Adani has been unable to find direct funding from any bank because of the reputational risk involved to anyone linked with the mine. The State Bank of India actually withdrew a proposed loan in 2015 after intense public pressure, and other companies are said to have refused to work with Adani on the project.

Ben Burdett, one of the two protesters who clambered on to the SCG field, past bemused Indian fielders and the first crowd at a men’s international match since the pandemic, issued a statement: “Millions of Indian taxpayers who are watching the first game of the Indian cricket tour have a right to know that the State Bank of India is considering handing their taxes to a billionaire’s climate-wrecking coal mine.” This was not, then, a direct attack on cricket or one of its corporate sponsors, but does hint at what is likely to come. Just as cigarette firms are no longer seen as suitable donors for sports teams, so big climate-polluters will become increasingly undesirable as commercial partners. The invaluable youth market, one that poll after poll reveals to be increasingly panicked about the state of the planet, will demand it.

Recently, Tottenham have come under pressure because their shirt sponsor AIA (an insurance company based in Hong Kong) is reported to have more than £3bn invested in coal. Spurs are not alone in having shirt sponsors from industries with dubious climate records but they are perhaps more vulnerable to pressure because of their reputation as a club that care about their own environmental stance. In October they signed up to the Count Us In initiative, which, among other things, promises to “choose financial institutions and funds that invest responsibly”.

Over on planet cricket, the Indian Premier League’s array of sponsors – including (purely for your entertainment) an official confidence partner, official hygiene partner, official smile partner, stamina partner, official mask partner and official goodness partner among others – is dazzling. Chennai Super Kings are owned by India Cements (the cement industry counts for 8% of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions) and sponsored by Gulf Oil; Sunrisers Hyderabad are sponsored by JK Lakshmi Cement. Meanwhile, Cricket Australia’s sponsor Alinta Energy is the seventh biggest climate polluter in the country.

In the febrile financial seas in which we are currently bobbing, sports would not be blamed for clinging to any old port in a storm. But Forest Green Rovers, the famously sustainable League Two football club that have been certified carbon neutral by the United Nations, have seen their sponsorship revenue double over the past year, despite the after-effects of Covid. Gloucestershire CCC, the first UK cricket signatory to the UN’s Sports for Climate Action Framework, have found similar enthusiasm for their environmental stance. Forest Green’s owner, Dale Vince, has said that many of their new sponsors have come not from companies traditionally linked to sport, but from “the emerging or developing field of environmental products and services”.

The post-vaccine world that we crawl towards in the spring has the chance to be a better one. Cricket’s place during the pandemic, a pocket of hope on a mud-splattered rec, gives it the status to make bold climate choices and makes it a place where decisions, like the Adani dam, can be held up to the light.

• This is an extract taken from The Spin, the Guardian’s weekly cricket email. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport