How the FBI won ‘the World Cup of fraud’ as Fifa scandal arrives in court

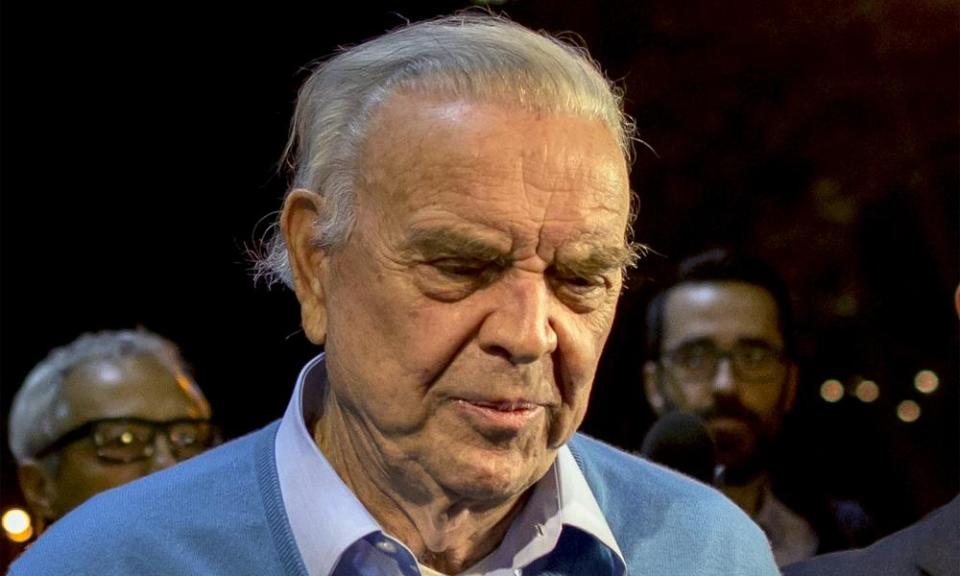

On Monday in a spartan Brooklyn courtroom, three former South American football chiefs accused of taking bribes and corruption will finally reach criminal trial, two and a half years on from the arrests in Zurich of Fifa barons that led to the toppling of Sepp Blatter’s regime. The three denying charges that include racketeering and “multiple acts involving bribery” over the sale of Copa América and other television rights are José Maria Marin, former president of the Brazil football association (CBF); Juan Ángel Napout, a Paraguayan who used to be president of the South America football confederation (Conmebol); and Manuel Burga, president of the Peru FA for 12 years and a member of Fifa’s money-dispensing development committee.

Substantial figures as they are, much more significant when assessing the impact of the US investigation into Fifa is to consider the former masters of the football universe who have already pleaded guilty, and the others charged but opposing extradition.

The latest to-do list for the presiding judge, Pamela Chen, states that 23 former football administrators and marketing executives have admitted guilt to crimes of financial corruption. They include Jeffrey Webb, who was president of the Confederation of North, Central American and Caribbean Football Associations (Concacaf); Costas Takkas, one of Webb’s fixers; Alfredo Hawit, who took a $250,000 bribe when he was the interim Concacaf president; and two sons of Jack Warner, the long-term Concacaf president, who is also charged with serial corruption.

The guilty plea dramatically unsealed last Monday from the FBI’s investigation into the alleged links of Donald Trump’s presidential campaign with Russia carried the hallmarks of the methods that unearthed the corrupt Fifa panjandrums. When the seven executives were hauled out of their beds in Zurich’s five-star Baur au Lac hotel and accused of the “World Cup of fraud”, the US Department of Justice revealed that one baron at the heart of it all, Charles “Chuck” Blazer, had already pleaded guilty.

The American’s flip from Fifa powerbroker to admitted fraudster and informer echoes that of George Papadopoulos, the former Trump campaign foreign affairs adviser revealed to have pleaded guilty to lying, who is now believed to have worn a wire since in conversations with associates. The exploration by the FBI, the Internal Revenue Service and the Department of Justice of endemic corruption in football followed the template now believed to be operating in the presidential investigation. They pinned Blazer with his undeniable guilt, secured his agreement to inform on others, then moved on to those whose names he sang. Investigators followed the evidence, and the money, secured more guilty pleas and informants, and proceeded to the next targets.

One crucial witness for the ultimate compiling of an indictment against 27 defendants, a who’s who of football potentates in the Americas, was clearly José Hawilla, the former president of Traffic, a prominent marketing company based in Brazil. Traffic was famed for having brokered a $160m deal in 1996 for Nike to sponsor the Brazil national team for 10 years. In his admission of guilt, Hawilla told the authorities he paid a kickback of $20m to Ricardo Teixeira, the long-term CBF president and a member of Fifa’s executive committee.

Hawilla, who awaits sentencing, illuminated in his guilty plea the culture of entitlement that had enveloped the heights of world football administration. He said he started Traffic as a legitimate company, buying South American football TV rights and selling them to broadcasters. But then the Paraguayan Nicolás Leoz, another of Fifa’s most powerful chiefs, president of Conmebol from 1986 to 2013, demanded the first bribe as long ago as 1991: “Leoz told Hawilla … that Hawilla would make a lot of money from the rights he was acquiring,” the indictment stated. “Leoz did not think it was fair that he did not also make money. Leoz told Hawilla that he would only sign the contract if Hawilla agreed to pay him a bribe.”

Hawilla said that from then on his company was endemically corrupt. Routinely, on almost every major deal to buy TV rights for the great South American football countries, he had to pay bribes, to Leoz, Teixeira and other football bosses, including Julio Grondona, president of the Argentina FA from 1979 and a central power-broker in Blatter’s Fifa until his death in 2014.

Blatter, whose 2015 election for a fifth term as Fifa president was scuppered by the arrests, still seethes about the US’s ruthless intervention. He argues, with some justification, that the corruption charged was in the Americas, and had nothing to do with Fifa in Zurich, which should not have been targeted. Blazer helped himself to piles of dollars from his base in the heart of the US, Trump Tower in New York, not at Fifa HQ in Switzerland.

But these complaints ignored the gross instances of alleged corruption that did relate to Fifa business. The worst accusation of all at the heart of the initial 164-page indictment was that Jack Warner of Trinidad & Tobago, for 21 years the head of Concacaf, had taken a $10m bribe to vote as a Fifa executive committee member for South Africa to host the 2010 World Cup. Blatter, when I interviewed him last summer for my book, The Fall of the House of Fifa, was scathing about Blazer, who had gorged on corrupt gains over 21 years as Concacaf general secretary and a Fifa executive committee member. “Blazer was at the [London 2012] Olympics as a representative of Fifa, and he was wired by the FBI,” Blatter lamented. “So, what is such a country trying to give us lessons in how to honestly do a job?”

Blatter will always believe that the FBI and IRS began their work, with a tap on Blazer’s shoulder on 56th Street in Manhattan in November 2011, because the US was resentful that Fifa had spurned its bid to host the 2022 World Cup and voted for Qatar instead. Yet that overlooks some blatant episodes. Corruption was in effect publicly advertised in Trinidad in May 2011 by the handing out of $1m in $40,000 payments, literally in brown envelopes, to delegates of FAs in the Caribbean Football Union (CFU) on the order of Warner. The payments followed a meeting at which the delegates were addressed by the Qatari Mohamed bin Hammam, who was standing as a presidential candidate to challenge Blatter in that month’s presidential election.

Warner denied it was bribery; Bin Hammam was found by the court of arbitration for sport to have been “more likely than not the source of the money” and was later banned from football for life.

The other problem with Blatter’s fixation on the Qatar vote is that a criminal investigation – whatever prompted it –would amount to nothing if there were no corruption to find. By any measure, with its guilty pleas, confiscation of assets and the threat of long jail sentences, the US evisceration of football authorities has been astonishingly successful.

Once they got going on the Trinidad dollars, subsequent public allegations made by Warner against Blazer, and the emptiness where Blazer’s tax returns should have been, the investigators unearthed mountains of dirt. Blazer, who died in July this year, pleaded guilty to 10 criminal charges in November 2013: tax fraud, racketeering, his $1m share of the alleged $10m South Africa 2010 bribe, and multiple, serial bribe-pocketing for selling TV rights to Concacaf’s international Gold Cup tournaments dating as far back as 1993. In his formal plea and agreement to cooperate fully with the investigation, Blazer admitted to all of this and said: “I knew that my actions were wrong at the time.”

Yet through those years when Blazer was travelling the world in private flights, staying in five-star hotels, feasting at the heart of football in the US, all the while wielding World Cup hosting votes and leverage at Fifa, he gave no indication that he knew any of his actions were wrong. Contemplating these men awaiting trial this week, or those to be sentenced after admitting guilt, it is jolting to recall how untouchable they appeared for so long.

Warner, charged with the $10m bribe and corruption on TV deals dating back to 1994, has been characteristically contemptuous of his accusers and remains in Trinidad contesting the law on extradition to the US. Teixeira, who has not admitted any wrongdoing, is in Brazil, which has no extradition treaty with the US. Leoz’s lawyers have always said he is innocent; he is reported to be under house arrest in Paraguay and contesting extradition.

Marin, Napout and Burga will finally have their opportunity to defend themselves in court. But given the guilty pleas of so many other former inhabitants of world football’s heights, the “World Cup of fraud” has already been proven.

David Conn’s book, The Fall of the House of Fifa, is published by Yellow Jersey

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport