Football abuse: from one lone voice to a national scandal

Two weeks after Andy Woodward told of his sexual abuse as a young player, English football faces the worst crisis in its history

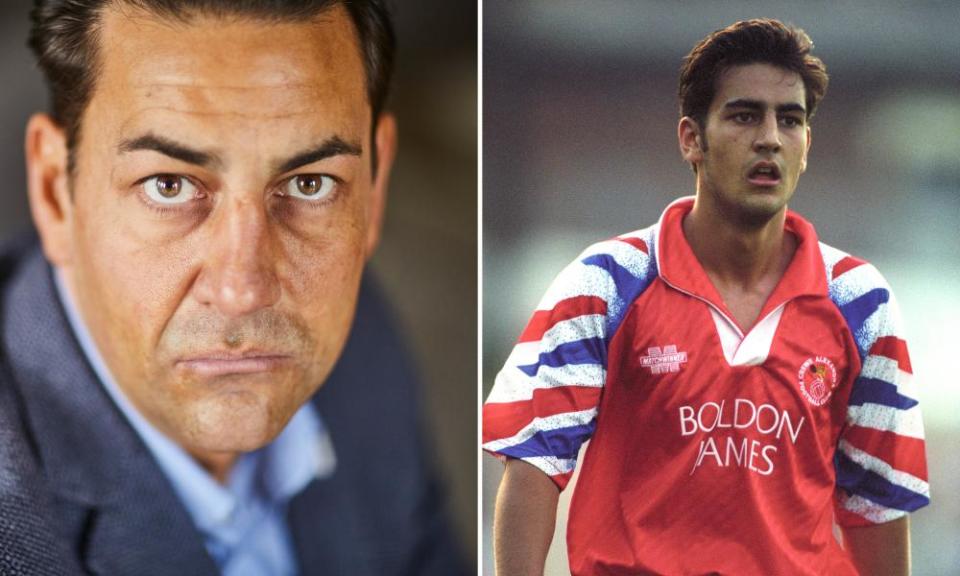

It began with the former footballer Andy Woodward bravely stepping out of the shadows to describe to the Guardian the sexual abuse he endured as a young player. Two weeks on it has spiralled into a scandal engulfing clubs and communities across the UK.

By Friday, 18 police forces were investigating leads from at least 350 alleged victims, the NSPCC children’s charity was processing almost 1,000 reports to a hotline and one of the world’s most famous clubs, Chelsea, was facing questions about whether it had tried to hush up abuse allegations.

All those involved – police, football administrators, players and their relatives, children’s charities, lawyers – are convinced it will not end here.

The former England striker and NSPCC ambassador Alan Shearer was the latest to express his shock at what has emerged and solidarity with those who had come forward.

“Over the last week I have been shocked and deeply saddened to hear of the abuse that colleagues, and in some cases former team-mates, suffered,” he said.

“I have nothing but huge respect and admiration for all the players who are now coming forward, bravely breaking years of silence in a bid to help others. They’ve carried a terrible burden for too long.”

Shearer sought to reassure parents of children who would be playing football this weekend that changes had been made.

“We can never be complacent but thankfully huge progress has been made in the last 10 years when it comes to safeguarding. All clubs now have dedicated people tasked with keeping kids safe, but there’s always more to be done.”

He also made it clear he believed the scandal was likely to escalate. “As the weeks go on, it seems likely that there will be more people coming forward who suffered abuse within football, and they will need to be given our support so as they can get the help they need and should have had years ago.”

Two players at Newcastle United were among those who came forward this week. Derek Bell told the Guardian how he was groomed and violated between the ages of 12 and 16 by the convicted paedophile George Ormond, his coach at the Montagu and North Fenham boys football club.

Ormond went on to become involved in youth coaching at Newcastle, where he abused player David Eatock, during the Kevin Keegan years in the 1990s. “I can still remember the look on his [Ormond’s] face, how terrifying it was, and how his eyes were possessed,” Eatock told the Guardian.

The former England, Manchester City, Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur player Paul Stewart described in harrowing detail how he was abused by the late Frank Roper, a well known youth coach in the north-west of England.

“He said he would kill my mother, my father, my two brothers if I breathed a word about it,” said Stewart. “And at 11 years old, you believe that.”

Individual clubs including Newcastle, Manchester City and Crewe have launched inquiries into how they handled allegations of abuse, or coaches who had turned out to be offenders.

On Tuesday, the former coach Barry Bennell was charged with eight offences of sexual assault against a boy under the age of 14. The offences allegedly took place between 1981 and 1985.

The Football Association has launched an independent review, which will be led by the barrister Kate Gallafent QC, who specialises in human rights and sport.

The FA chairman, Greg Clarke, described it as one of the biggest crises in the organisation’s history. Asked about claims that clubs may have tried to bribe players to stay silent about their abuse, he described the concept as “morally repugnant”. He has promised that any club guilty of “hushing up” sexual abuse to protect their image will be punished.

That promise may be tested after the Daily Mirror revealed that the former Chelsea player Gary Johnson signed a confidentiality agreement with the club in 2015 in return for £50,000 after he alleged he was abused by the club’s then chief scout Eddie Heath in the 1970s.

“I think that they were paying me to keep a lid on this,” he told the Mirror. “Millions of fans around the world watch Chelsea. They are one of the biggest and richest clubs in the world. All their fans deserve to know the truth about what went on. I know they asked me to sign a gagging order and how many others are there out there?”

Chelsea has refused to comment on the details of the allegations, only saying that it has appointed an external law firm to carry out a formal investigation into a former employee, and would pass those findings on to the FA.

On Friday, Southampton, a club renowned for its youth system, said it had contacted the police after receiving information in relation to historical child abuse. It followed BBC interviews with two former players, Dean Radford and Jamie Webb, who said they were groomed and abused by a former club employee.

Police chiefs said there was no sign of any let up in the reports of abuse. By the end of the week Greater Manchester police said it had identified 10 suspects after receiving reports from 35 victims. The priority for forces was to assess whether those named posed a present risk to children, and to deal with them before moving on to investigate historical abuse claims.

But the allegations emerging are not confined to football, or even to sport.

The National Association for People Abused in Childhood (Napac) said it had seen a tenfold increase in the number of adult survivors of child abuse registering for its support groups, rising from 10 registrations a week to 100 in the last three weeks.

The Napac chief executive, Gabrielle Shaw, said: “This is not just about football; huge numbers of people suffered abuse in childhood, within the family or institutions. Survivors often feel shame, pain and confusion about what was done to them.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport