Spectacular goals at risk of dying out in the Pep Guardiola era

It was a particularly fine Goal of the Month in December 2006. Adrian Chiles introduced the BBC and Lightning Seeds institution from an FA Cup third-round match between Tamworth and Norwich City. “A really rather cracking December goal of the month competition,” he says, before we cut to Bramall Lane.

A long throw is launched into the box and headed clear to the D where Keith Gillespie thwacks an imperious volley into the corner. Morten Gamst Pedersen does the sort of thing you remember him for. Matty Taylor scores the Matty Taylor goal. Paul Scholes’ Villa Park volley, then Michael Essien with a rising curler at Stamford Bridge hit from approximately Earl’s Court.

What is striking is the audacity and the range, not just of shot but the differing type of goals. Such variety is vanishing from the current Premier League. In videogame circles it was once considered a faux pas to find space close to the byline and cut the ball back across goal for an easy finish. Now goals like those seem like the only way to get ahead.

It goes beyond the goals, there is a clear flattening of styles in the top flight. Control is everything and teams are more regimented in the way they move, with the ball and without it. Spontaneity is more likely to get you substituted than applauded. Whenever a new coach is appointed they will generally say the same thing. They like to keep possession, play at a high tempo, press and win it back quickly.

We have just seen two ludicrous games involving Chelsea in the space of six days, their 4-1 at Tottenham then a 4-4 draw at Manchester City. In that light this is a counter-intuitive question to ask. But has Premier League football become more boring?

Perhaps we are all just more aware of football’s inner workings. Wolves manager Gary O’Neil appeared on Monday Night Football last month to demonstrate the clever way his double-pivot in midfield had trumped Bournemouth’s attempted press. Depending on your view this was either a thrilling glimpse behind the curtain or a slightly depressing reflection of how little freedom is given to talented footballers.

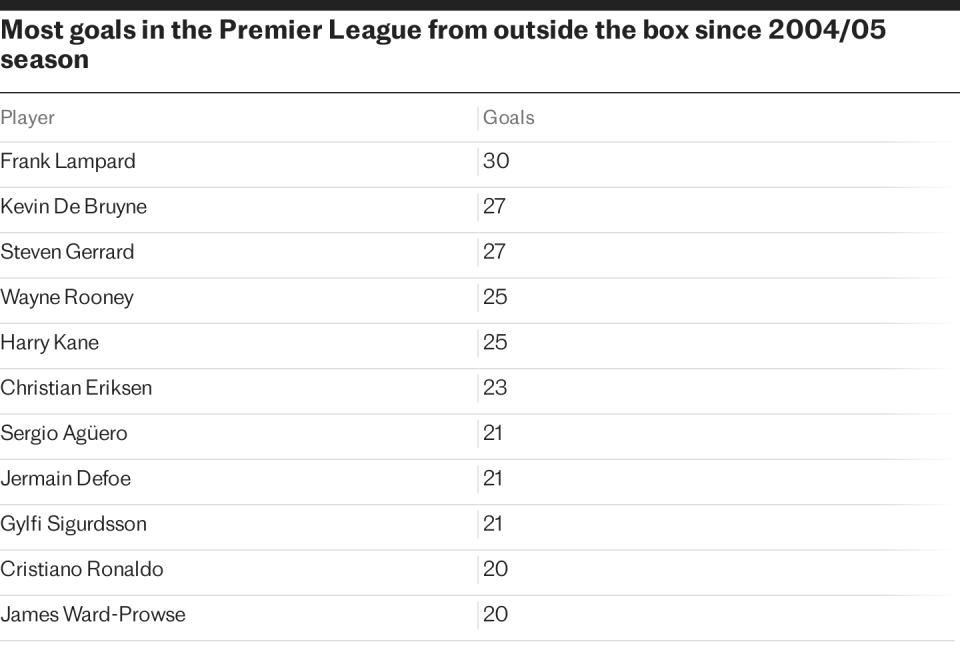

Risk-taking is on the wane. In the past 20 years there has been a steady reduction from around 13 shots per game from outside the area to closer to nine currently. The headed goal is also in decline, accounting for nearly one in five Premier League goals in 2004/05, now more like one in 10. Direct free kicks are going the same way as shots from outside the box, although goals from outside the area have held steady, suggesting players are being cleverer about choosing which shots to take. Or they are under strict instructions. You imagine the average xG of Tony Yeboah or Matt Le Tissier shots would now be a cause for disciplinary proceedings.

A rare critical voice was raised from within the coaching fraternity last year. “A robotic game is being made,” said Cesc Fabregas, then with Monaco now at Como, and speaking to Marca. “You watch games and you know what is going to happen. A little pressure, a long ball behind the back, the striker pushes it to the end or for the midfielder to arrive and it becomes very monotonous in many teams.”

If you must have a villain, make it Pep Guardiola. Success is the most powerful propaganda for orthodoxy and the brilliance of his highly-regimented methods are being copied around the world. Few dare to try anything different. Thomas Frank’s Brentford have had a mild minority of possession in the Premier League this season and other outliers exist in specific scenarios, like Ange Postecoglou’s novel decision to set an offside trap on the halfway line when down to nine men against Chelsea. Only Diego Simeone is a consistent dissenter at the top level, and you sense few coaches are namedropping him in job interviews.

‘Players do it because they get the rewards’

So how are the perfectionists and detail-oriented football obsessives transmitting their ideas? “I’ve gone to clubs abroad and watched an hour spent on throw-ins,” says Mark Warburton, former manager of Brentford, Rangers, Nottingham Forest and QPR. “I think it’s not completely rigid like NFL, with specific plays. But I think we are definitely gravitating towards aspects of the game which are far more structured and pre-prepared.”

Patterns of play have been worked on for years down to non-league level, but they are more detailed now and designed to create specific scenarios on the pitch, especially the contrived overloads so key to success for Guardiola’s Manchester City. Most coaches now run shorter training sessions, but at a higher intensity. Time in the video analysis room makes up for the deficit.

It does not sound like much fun. “Players aren’t stupid,” says Warburton. “If they see something benefit them, even if they hate doing it, they’ll do it because they get the rewards. But sometimes the level of detail is extreme. If there is an individual moment of genius, a player drops a shoulder and beats two men, then your best-laid plans are out of the window.”

It is not all Guardiola’s fault. The standardisation of coaching courses churns out graduates with broadly similar views and the rise of data means many English clubs employ multiple analysts. “Data is massive and many people don’t appreciate how important it is, but it can’t be everything,” says Warburton.

“Recruitment can’t be 100 per cent data led. But it’s certainly having a huge influence on the game and that will certainly increase over the next three to five years. It just can’t be to the detriment of any aspects of the game that we all love.”

How much these changes matter will depend on your general outlook. A football fan can still enjoy the sport in its most basic form, untroubled by secret pressing triggers, should they choose. But there is a sense that something is being lost.

‘Very risk-averse’

Nick Hancock once depended on the volatility of football to make his living. The host of They Think It’s All Over now helms the podcast The Famous Sloping Pitch and laments the loss of a more unpredictable time. “Players are much better and much fitter and have a wider range of skills, but that doesn’t make the game more exciting,” he says. “I hear people at games slagging off players for doing things and I’m thinking ‘they’re only doing exactly what they’re told.’ The days of a player grabbing the game by the scruff of the neck and turning it around are kind of gone.”

His view is that today’s more preordained style is a product of saturated football coverage and a fear of failure. “I get the feeling that the players and the officials are never as happy as when there’s a break in play, because they can’t be guilty of anything.

“Pressure and judgement makes the game very risk-averse. That’s magnified by the fact that they’re always trying to inoculate the game from human error. That’s exactly what the game isn’t. It’s sublime skill and athleticism but it’s also about the fallibility of human beings. By having perfect pitches and seven substitutes, all of those things are there to help guarantee that the right team wins.”

It may be some time before we see a proper clash of styles again. The crazy gang cannot beat the culture club when everyone is a culture club. “Teams will evolve to join the possession trend that is clearly the current blueprint for success,” says Jack Manship, an analyst and scout for Doncaster Rovers. “Teams like Brighton, Aston Villa, Newcastle who, sure, never used to park the bus for long periods of time, are now dictating the play in a lot of their games, which is why they find themselves in much stronger positions than they have in the recent past.

“It’s also no coincidence that most of the teams who have the least possession on average are down near the bottom of the Premier League this season.”

He sees ultra-defensive tactics going out of fashion before Pep-lite football, and Warburton expects a future which is even more influenced by Guardiola. “I think we’re going to see a complete breakdown of formations as we know them. Various coaches have always done various tweaks but I think now, with Pep especially having a huge influence, we’re going to see formations go.

“Your centre-half will end up wide left and we’ll produce players who are more comfortable in all areas. The days of a big Jack Charlton-type centre-half are going to be gone.” That is at least a different sort of unpredictability and excitement. Where do you get your kicks, jinking wingers or subtle in-game tweaks from a 3-4-3 to a 2-4-3-1?

For now at least the noise and fury of the Premier League frequently still seems as vital as its adverts. Slowly though, expect a further slide towards regimentation. If current trends continue football will become ever-more refined, optimised, and ultimately charmless.

Think of your gun-to-the-head favourite match of all time. Was it impeccable or was it loose, wild and unhinged? In future that second category may no longer exist.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport