Gary Lineker lip-syncing on Wogan and Marco van Basten’s volley – last time Germany hosted the Euros

Euro 88 has a rare distinction. It was the last international football tournament that featured neither a sending-off nor a goalless draw and in which none of its knockout matches went to extra time or penalties. Mind, there may have been a reason for that: the competition, hosted in what was then West Germany, consisted of only 15 matches. As opposed to the 51 that will take place in the united Germany over the next few weeks. In the days before tournaments became ever more bloated, this one featured just the two groups of four, with two countries qualifying from each into a semi-final. It was all over within a fortnight. And for England things were even more succinct: they were back home within six days.

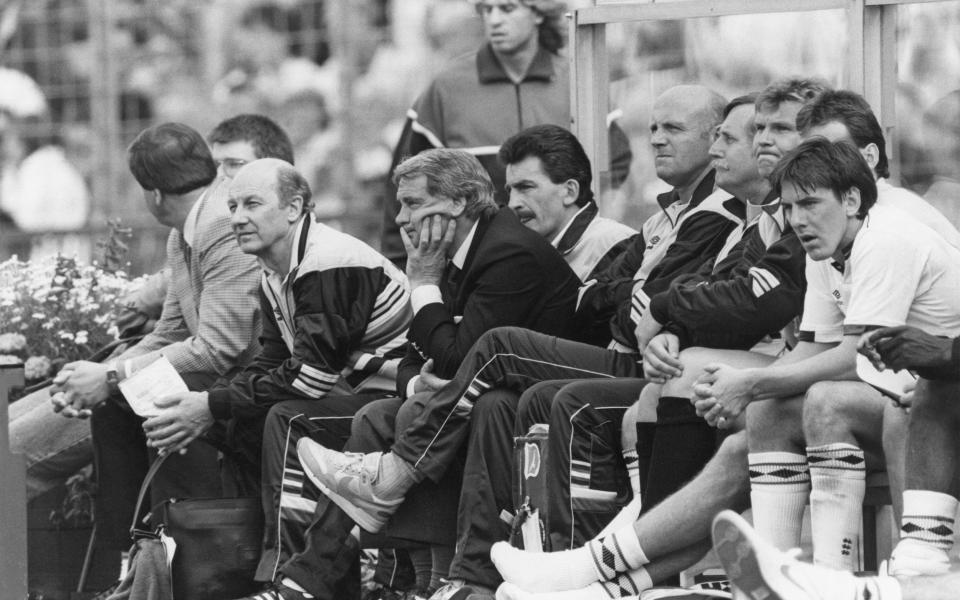

Some 36 years on, though, it is not its brevity, nor the lack of goalless draws or red cards for which the tournament is largely remembered. Nor is it for the official England song, lip-synced on the Wogan show by Bobby Robson and his squad (Gary Lineker juggling a football, Tony Adams in the background attempting to lift weights in time to the music), which has legitimate claim to be the most embarrassing football number ever committed to vinyl. To add to its comedy value it was titled – ironically, given how the team fared – We’re Going All The Way.

Back in 1988, the England football team appeared on BBCs Wogan show with their Euro 88 song… 'We're going all the way'

In the tournament…

Played 3

Lost 3

Finished bottom!#England #Euro2020 #Euro88 pic.twitter.com/pSJ3pNwNkO— TV Football 1968-92 (@1968Tv) July 13, 2021

No, the tournament is largely sealed in the public memory for a goal that may well be the finest ever scored in an international final. It came in the 54th minute of the match between Holland (as they tended to be called back then) and the Soviet Union (a political entity participating in its last ever European championship). The game was played at the Olympic Stadium in Munich, because in those days Berlin was a city divided between east and west. And Holland were some side. With Ruud Gullit and Marco van Basten in their pomp up front, and a pair of ball-playing centre-backs operating behind them in Ronald Koeman and Frank Rijkaard who were way more technically gifted than the brutal stoppers of the era, they were easily on a par with the great Dutch XIs that had reached the World Cup finals in 1974 and 1978. And they soon took the lead, thanks to a Gullit bullet of a header.

But it is what happened nine minutes into the second half of the game that still resonates down the years. After the Dutch had engaged in a lengthy period of possession, the ball was passed out to Arnold Muhren on the left wing. The veteran former Ipswich and Manchester United midfielder, who had just celebrated his 37th birthday, dispatched a cross which wafted over the heads of both the Soviet defenders and the Dutch attackers, apparently drifting harmlessly beyond any threat. Except that Van Basten, whose hat-trick in an earlier group game had accounted for England, was lurking at the far post. And somehow, from an angle so acute it seemed to defy all laws of geometry, he launched a devastating volley, which flew beyond the Soviet keeper Rinat Dasayev, a last line of defence so difficult to breach he was nicknamed The Iron Curtain, before he had even noticed it was coming.

For a moment the stadium was stunned into silence. Even Van Basten, as he wheeled away in celebration, seemed astonished. Rinus Michels, in the midst of his third spell as Dutch manager, may have been the architect of total football in his time at Ajax in the 1970s but he looked utterly amazed by his striker’s dexterity. He put his hand over his eyes as if he could not believe what he had seen. Many years later, Muhren admitted he had mishit his cross, sending it far further than he had intended. It was, he said, “a poor ball. Marco made it beautiful”. He was right there.

The celebrations in a stadium which appeared to have turned orange for the occasion were extensive. But oddly, they were not as pronounced as they had been when the Dutch had overcome West Germany in Hamburg in the semi-final. That occasion, according to the writer David Winner in Brilliant Orange, his book about the Dutch football revolution, had sent the entire nation delirious, the celebrations extending over days. Indeed the Dutch team had got collectively plastered after their win before the next evening heading off for a drunken group outing to watch a Whitney Houston concert. And that even though there was a final to be played just three days later.

In part, the reckless hue of the reaction was due to the lingering memory of the German invasion of the Netherlands 48 years previously. One group of the thousands of Dutch supporters who had poured over the border for the tournament brought with them a banner which neatly referenced the past plundering of their nation by the invaders. It read: “We’ve come for our bicycles.” But Gullit reckoned the delight was largely in response to more recent events. It was revenge for the defeat to the Germans in the 1974 World Cup final, when Johan Cruyff’s magnificent team had failed at the last.

“Fourteen years before, the whole country had sat weeping in front of the television as they watched the Dutch suffer defeat,” he said. “We had come to put that right.”

Hans van Breukelen, the goalkeeper who saved a Soviet penalty in the final, was more to the point. “The semi-final win was much more important for us,” he said.

But even so, they completed the deal and won the final, Gullit lifting the trophy in sheer delight. It remains, like England’s 1966 victory, the only time the Dutch have ever won an international tournament. Its excellence, however, still lingers.

Which is more than can be said for England. Playing in only their third Euros finals, they lost all three of their group games. Despite boasting players of the calibre of Bryan Robson, Peter Shilton and Glenn Hoddle, they were beaten by Ireland, Holland and the Soviets in the group stage. It was a miserable campaign, which suggested the continuing post-Heysel ban on English clubs’ participation in European competition was having a profound effect on the international side. Indeed it is unlikely to be a tournament Gareth Southgate, always assiduous in his referencing of history, will have brought to the attention of his players as they head to Germany 36 years on. Unless it was to tell them how not to do things.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport