Geoff Capes: ‘If eight or nine tried to fight me – I would ask for more’

Six pounds of red meat. A dozen eggs. A large tin of baked beans. Two tins of pilchards. One and a half pounds of cottage cheese. A packet of cereal. Two large loaves of bread. A pound of butter. A pint of orange juice. And seven pints of milk.

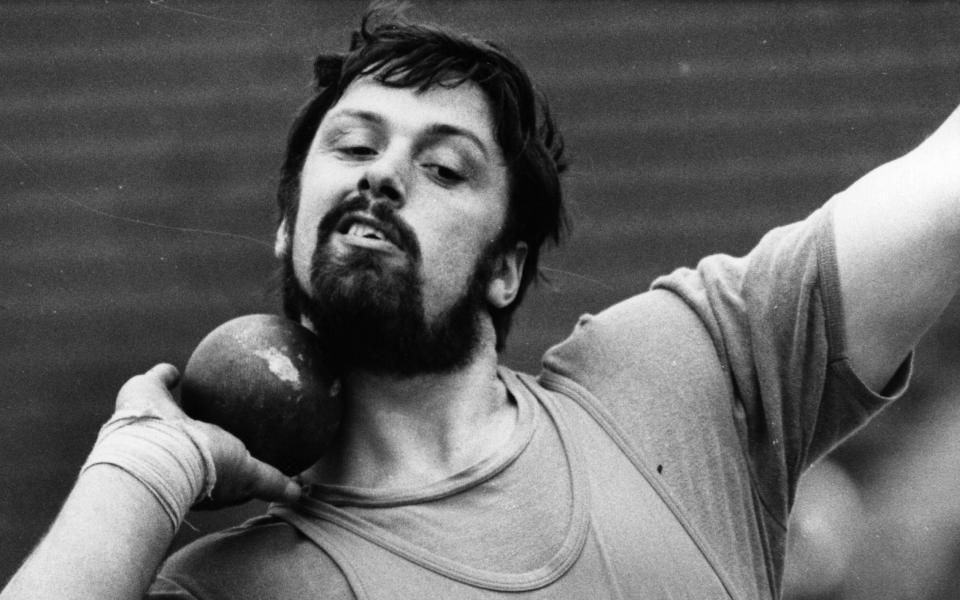

No, this was not a family’s weekly supermarket order. It was simply the daily intake of a man who was once not just officially the strongest man on the planet, the best shot putter in the world and a six-times Highland Games Champion, but the winner of a world title for breeding budgerigars.

Geoff Capes was also one of the most recognisable faces in the country, appearing prime time on every programme you can imagine from This Is Your Life and the Sooty Show (where Sweep dreamed of beating him at the tug of war) to Blankety Blank and Super Gran (who he nearly killed with a stray throw of an enormous tree trunk).

Now 73, Capes is seated in a chair that looks like the throne of a giant fairy-tale king and simply raises an eyebrow as I read aloud his old food diary.

“Twelve eggs!?” he snorts. “I could eat that now. I ate like a f------ horse! Anything I could get my hands on. But nearly all protein. It’s like a steam engine. Put the coal in. I was burning up to 10,000 calories every four or five hours.”

Capes, who would lift 120 tonnes in training per week, then smiles as he recalls the sponsorship deals that helped him bypass amateur rules that once governed Olympic sports like athletics and swimming.

“Butcher Brown is the best in town,” he says, parroting the slogan from one meat provider, before remembering how his Talbot Estate car had the words ‘Dewhurst: Master Butchers’ emblazoned on the side. It was a small price to pay for an endless supply of steak. There were also deals with the Glenryck pilchard company and a local milk producer.

“My weekly wage with the police was £9.50 – so I couldn’t live off that,” says Capes, who succinctly sums up the official assistance for athletes like him who were combining full-time jobs (often on night shifts) with regularly travelling the world to represent their country. “It was, ‘Look after yourself mate’,” he says.

Some would suggest that not much has changed and Capes, who has continuously held the official British shot put record for 51 years, remains an encyclopedic and avid student of the sport. “It’s a bit thin, isn’t it?” he says, assessing what will be the smallest Great Britain squad at a World Athletics Championships since 2005. There will be only two men across the entire field event programme, although that will include Scott Lincoln, a shot putter who is now within 40cm of Capes’ 21.68m British record – which you can see him throw below.

The great hope is that the forthcoming World Championships can help elevate British athletics’ profile towards its high water of the late 1970s and 1980s when people such as Capes, Seb Coe, Steve Ovett, Fatima Whitbread, Steve Cram, Kathy Cook, Daley Thompson and Tessa Sanderson became household names.

“We were all a gang of mates but superstars in a way,” says Capes. “We each had our own image and, if you took one per event, we were the best team in the world.“

Capes now worries for the grassroots, but there is huge excitement over the progress of two of his grandchildren, 18-year-old Donovan and 14-year-old Lawson, who train at the shot put ring he built in his home village of Stoke Rochford. Donovan won the English schools title in 2019 and is heading to the United States on a scholarship while Lawson is currently the best Under-15 in the country by a mammoth two metres. “Donovan will improve and Lawson? Watch that b-----,” Capes tells me.

They are both coached by Capes’s son Lewis, himself an accomplished former shot putter and American footballer, and they have photos and memorabilia from their grandfather’s career displayed all over the shed where they do their weight training.

Lewis then shows me a recent video of Lawson adjacent to old footage of his 6ft 5in grandad. The resemblance in their shot-putting technique is extraordinary.

“There’s a lot to get right across that seven-foot circle and you expend as much energy in that two seconds as a 200m sprinter,” explains Geoff, who is sent regular footage of the boys in action to then relay feedback.

The common family thread is the speed and timing of a rare explosive power. Lawson can run 100m in 11.6secs. His grandad once got down to 11.2sec and, even when he weighed 23 stone, could still run 200m in 23.7sec, which was fast enough to famously beat Brendan Foster in a race. “I had the same muscle fibres as a sprinter,” says Capes, whose daughter Emma was another national schools champion and a medallist in the junior Olympics.

Capes was also born with a rare natural size and, coming from a family of nine children in the Lincolnshire Fens, overcame considerable childhood challenges.

He combined his schooling in Holbeach with lifting sacks of potatoes on a farm and was frequently in trouble with authority.

“Boy spelt backwards is yob,” he says. “I was a hell of a fighter as well. If the next town came down on a Friday and there were only eight or nine of them I’d say: ‘Go back and get some more.’ I’d fight them on my own. I was quite quiet but there was an inner aggression.

“My headmaster, a guy called Joe Fathers, took great pleasure trying to knock it out of me. He was ex-Borstal. He had a choice of canes. He’d hit you anywhere – across the knuckles with a two by two. He tore my ear. On the last day I went into his office, I took the canes off the wall in the office in front of him, and walked out.”

A talent for athletics had also become evident and, in 1964, Capes competed in the same English schools championships that his grandchildren have since won.

“I threw in bare feet in a concrete circle – and came second from last,” he says. “My mother was a matron and all of my clothes came from the old people’s home after people had died.”

Capes, though, had discovered an avenue to channel what he calls the ‘chip on my shoulder’ and, after meeting Stuart Storey at the local club and offering to carry his spikes, found a life mentor.

Now 80, Storey became best known as the BBC athletics commentator from 1973 until 2008 but he was also a 1968 Olympian in the 110m hurdles and has never forgotten his first meeting with the man he still calls ‘Geoffrey’.

“He was a ruffian,” says Storey, who compares Capes and athletics with a young boxer from a tough neighbourhood in Detroit or New York who had sensed a route out.

Capes, who would hitchhike to athletics competitions, was told by Storey that he could achieve great things if he would just direct his energy. They then went off on a mutual journey of discovery in the shot put that would end with Capes becoming Britain’s most capped athlete, a double European and Commonwealth champion as well as a 17-time national champion.

An Olympic medal, however, would remain elusive and there was no World Athletics Championships until 1983. Capes did compete at three Olympics, including the 1976 and 1980 Games as one of the favourites for gold, but finished respectively sixth and fifth behind podiums made up exclusively of throwers from East Germany and the Soviet Union.

Capes points out that it was later reported that some of those in front of him had “taken gear” and, as a police officer, his preparations for the 1980 Olympics were disrupted by concerted political pressure to boycott the Moscow Games.

“Russia invaded Afghanistan, and Margaret Thatcher banned all the services from going – army and police – because they paid their wages. So I resigned from the police just before the Olympics. I lost my career, lost my pension, lost my income. They had total control over you.”

Capes could see no future as an amateur and, while convinced that he would still have challenged for a shot put medal in 1984, a new career combining the World Highland Games with the increasingly popular and lucrative strongman circuit beckoned.

With Christmas television audiences at 15 million, victories in the World’s Strongest Man in 1983 and 1985 – as well as the European Strongest Man in 1980, 1982 and 1984 – made him more famous than ever. “I remember playing rugby at school and Dad coming over to tell me that he had won the world’s strongest man – but that I wasn’t to tell anyone as it wasn’t on television for a few months,” says Lewis.

The assortment of strength tests – bending steel bars, lifting a platform of bunny girls, rolling over cars, pulling lorries, loading sacks of sand onto the back of a truck, arm wrestles and tug of war – gave the show cult status. And Capes was soon in demand for everything from 17 pantomime appearances and children’s TV to performances at the Palladium with Bobby Davro and numerous television adverts (he famously gave the VW Polo a once over by rolling it from top to bottom and side to side).

Capes shakes his head when I say that it must have been quite nice to be known as the world’s strongest man.

“There were stronger people out there – I met a lot of them in the fens of Lincolnshire,” he says. “But it was about the application of strength. Can you apply it at speed? Can you run with 400 pounds? I basically did that on a farm when I was a kid with sacks of potatoes. And I worked things out technically. They would call me ‘numbers’. If I went first, you’d see everyone copying.

“When Strongman took over everyone assumed you were on gear [but]... I remained in the Highland Games which were tested. I was probably one of the most tested athletes there ever was.

“I was disadvantaged [in World’s Strongest Man]. I can tell you that. But I beat them in natural strength, speed, agility, coordination. It earnt me some money, and got me to a lot of places. We were basically mates. It is [sport] to a degree … but I’m not sure it would get past the Wada people.”

As we talk, the constant chirp of about 200 budgerigars from the shed adjacent to the conservatory provides a surprisingly soothing soundtrack. Capes got interested in breeding after seeing some in the home of a man he had arrested when he was in the police.

He liked the calming contrast with the aggression and intensity of his sporting life, which had also included becoming a black belt in aikido and judo.

He became the president of the Budgerigar Society and says that he has never been happier than when he won the world championships in the variety category. “No matter what it was, I wanted to win,” he says.

There is a battle now with his health following a stint in hospital earlier this year. “I’ve got all sorts wrong with me,” says Capes, who has ongoing weakness in his knees and shoulders and struggles to raise his arm. “I competed with so many injuries – sometimes you wish some of the people see what you gave.”

His mobility has been particularly impacted but there are no regrets or self pity and he assures me that he is “fighting back”. And the most natural smile of all comes when remembering the camaraderie and fun of his early athletics days, such as the disappearance of a 12-bottle case of whisky from a group of British officials at the 1972 Olympics, who had become renowned for their extravagant attitude to travel and fine-dining while athletes made do with a 50p daily food allowance.

“We were drinking it all through the Games,” laughs Capes, recalling not just how he was asked, as a policeman, by federation secretary Cecil Dale to investigate this ‘theft’ but how the athletes kept it secretly stored in the loft of their accommodation. “There were so many stories,” says Capes. “I had my time. I enjoyed my life and I went around the world. How many people can say that?”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport