Golden Goal: José Cardozo for Toluca v América (2003)

Team goals have a highbrow appeal of their own, and few have hit the heights like this euphoric crescendo in the Mexican league

There are multiple ways to score a goal, but none are as highbrow as the team goal. They stimulate the arty fart in every football fan. The main reason for that is that they generally involve lots of clever, elegant passing and movement. (Even though it was the work of three men, nobody called this a team goal.) The other is that – good morning Private Eye, ohayō gozaimasu Pseuds Corner – there is a creative grandeur to the team goal that you don’t find elsewhere. The thrill of the orchestra needs no explanation, and not only because we can’t think of an adequate way to convey it.

That thrill is greatest during the crescendo, which is the essence of any team goal. If you are lucky, the commentator will instinctively supply a vocal surge too – as Gerald Sinstadt did during a hypnotic commentary on Mick Channon’s Southampton’s famous goal against Liverpool in 1981-82 that is as near to perfect as dammit. There are so many moving parts to the team goal that it is rare and precious to see them all work in sync. The degree of difficulty and speed involved means that the goal is usually much greater than the sum of those moving parts – especially as it is the result of improv rather than a song sheet or a script.

Related: Golden Goal: Claude Makélélé for Chelsea v Tottenham Hotspur (2006) | Michael Butler

Toluca’s euphoric crescendo against América in 2003 is full of such improvisation, yet it is so serene, slick and knowing, with such perfect rhythm, that it almost looks scripted. In the context of a sport where imperfections happen all the time, the flawlessness is extraordinary. José Cardozo scored the goal, though Zinha and Rafael García deserve equal billing. The whole thing looks like CGI wizardry rather than the work of three footballers who, for a few beautiful seconds, entered the zone together.

The fact it came during a trouncing of one of their biggest rivals made it infinitely sweeter. The team goal is a statement of superiority at the best of times, a kind of legitimate showboating, but nothing says ‘I hate you’ quite like a swaggering passing move to go 5-0 up.

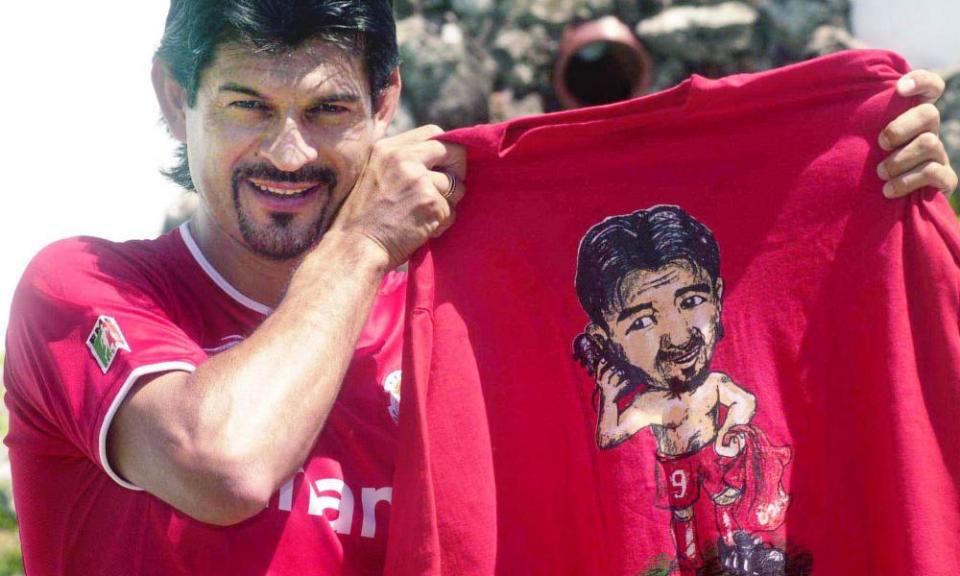

Extravagant minimalism

Cardozo is one of those South American legends that Europe never really got to know. He was part of Paraguay’s golden generation – everyone’s got one – and was the leading scorer in their history with 25 until Roque Santa Cruz overtook him. His 249 goals for Toluca remain a club record. That included a preposterous 36 in 25 matches in the 2002 Apertura, after which he was named South American Player of the Year – joining a reasonably prestigious list that includes Pele, Diego Maradona, Zico and Elias Figueroa.

It was in the following season’s Apertura that he and Toluca tore América a new aperture. The goal, which really deserves its own 1970s-style goal diagram, was the second of yet another Cardozo hat-trick. Toluca were 4-0 up when América went through the motions of another attack. Vicente Sánchez won possession near his own corner flag and pushed the ball down the line to Cardozo. Nine touches, five passes and 15 seconds later, the ball was in the net.

Related: Golden Goal: Esteban Cambiasso for Argentina v Serbia & Montenegro (2006) | Gregg Bakowski

A lot of team goals have some extraneous probing or keep-ball at the start of the move, which add quantitative but not qualitative value. Here, every touch – and one spectacular non-touch – has a specific, progressive purpose. The move is minimalist, yet also extravagant. It includes an elaborate dummy, a hurdle, a one-two, a back flick, a disguised pass, all kinds of off-the-ball movement – and a group of defenders who, at that particular moment in time, could have taken a polygraph test and would have sworn their name was Andy Wibble.

Each touch is more teasing than the last, until you feel like you can take no more. The best bit comes at the end: when García breaks through, you think that must be it; he’ll belt it past the keeper. Instead he uses the eyes in the side of his head to square the ball, take the keeper out of the game and allow Cardozo to reappear from out of shot to score an open goal. That final flourish of walking the ball in turns a great team goal into one of the greatest team goals.

It’s not only crescendos that reach a climax. Footballers frequently compare scoring to sex, and different types of goal evoke different images. Long-range belters are scored behind the bike sheds; at the other end of the scale lies the team goal, the culmination of luscious, seductive foreplay, an exponential sporting climax. Cardozo’s goal wasn’t just sexy football; it was tantric football.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport