Inside the push to stop female footballers suffering so many ACL injuries

“You start to blame yourself,” Claire Rafferty says. “I definitely did. I would go through different phases of feeling sorry for myself. Why? Why is it me? Am I doing something wrong? Am I not training hard enough? When actually it’s stuff that you can’t really see.”

Rafferty’s journey through three ACL injuries has been well documented and her legs bear the long scars of her many surgeries. The former England international’s injuries were sustained before the professionalisation of the top flight and semi-professionalism of the Championship but female players are still suffering knee ligament injuries in worrying numbers. Research shows they are four to six times more likely to suffer an ACL injury than male footballers.

Related: Eni Aluko takes job as Aston Villa Women's sporting director

Bristol City’s Abi Harrison, Brighton’s Ellie Brazil and Laura Rafferty, the England and Manchester City defender Aoife Mannion, Tottenham’s Jessica Naz, Crystal Palace’s Ashlee Hincks, Birmingham’s Heidi Logan and, for the second time, Arsenal’s Dan Carter have been sidelined in the past six months.

“Traditionally, a lot of the research was done on males and the transferability is hard because the two different populations are quite distinct,” says Dr Andrew Greene, a senior lecturer in Sport and Exercise Biomechanics at the University of Roehampton. “Women participating in team sports are four to six times more likely to get an ACL injury, depending on the task. They are also at greater risk of developing other lower-limb injuries. When you’ve got statistics like this floating around there becomes the need to try and investigate it.”

That is what Greene is doing. So the Guardian took Rafferty to meet the biomechanist and go through some of the testing being carried out there, for free, on female footballers, including Crystal Palace players, in the hope of reducing the risks of joint injuries.

Once the experts at Roehampton have assessed a player and developed an understanding of their lower-limb mechanics, they develop a targeted neuro-muscular training protocol to address problem areas or muscular imbalances.

When discussing what makes female athletes more susceptible to ACL injuries, Greene points to the 2010 paper by Hewitt and colleagues from the US, who discussed a number of ineffective or faulty movement patterns that appear to be present in female athletes.

“From a biomechanical point of view, the authors discuss four neuromuscular imbalances that may be present in female athletes, which appear to be associated with the underlying mechanism of ACL injury and which may contribute to an athlete’s inability to safely control their landings,” he says.

This, in Greene’s words, are what they are:

• “A dominance of the quadriceps. They are the stronger muscle group, are easier to train, are easier to activate, and so they can become dominant. Athletes often stabilise the knee with these muscles, underusing hamstring and gluteal muscles which can lead to an imbalance.”

• “Related to quadriceps dominance is becoming ligament dominant. When we land or when we absorb force, what we should be doing is activating all of the muscles around the knee joint to protect, control and stabilise the joints, rather than just the quadriceps, which act at the front of the knee. But if we don’t do that, whether it’s a weakness or an imbalance, then we can increase the stress on the ligament.

“Now, the ligament is only so strong and putting a lot of force through it and changing direction, twisting it or whatever, there comes a point where eventually it fails if it is not adequately supported by the muscles.”

• “The third issue relates to limb dominance. Football is a sport where we typically have a kicking limb and a non-kicking limb. And, again from a training perspective, they might develop slightly differently. If you think about it typically, if you’re right-footed, the left limb is going to be doing an awful lot more of the stabilising tasks when you’re kicking a ball. But then also changing direction you tend to push off on your dominant limb.

• “And then along with that comes the trunk and core. If you think of the trunk, everything in relation to changing direction or stopping/starting is trying to slow down the body. If we aren’t able to keep well aligned and keep well structured as we change direction, if our trunk flexes while we’re doing that, it shifts our weight, which changes the line with which the force goes through the joint.”

So would specific neuromuscular training programmes, which focus on rectifying an athlete’s imbalances, reduce their risk of injury? Two academic papers since 2018 have shown that may be the case.

A paper last year by Weir and colleagues tracks implementation of an “injury prevention programme” with Australia’s women’s field hockey team over two years alongside regular training. “Zero ACL injuries occurred after implementation,” says Greene of the study. “So, what that means, for me as a sport scientist, is that a targeted approach with a group of female athletes playing high-level sports can have an effect on that.”

Greene intends to work with female footballers this summer to implement similar programmes. “It’s incredible,” says Rafferty, a former Chelsea and West Ham player who retired at the end of last season. “Even if you reduce the likelihood by 10% or 5% I’m sure the likes of Emma Hayes [Chelsea’s manager] would be biting your arm off to do it.”

A further paper, Webster, from 2018, suggests “ACL injury prevention programmes” reduce the risk of ACL injuries by 50% in all athletes and non-contact ACL injuries by two-thirds in female athletes.

Rafferty is strapped into the isokinetic dynamometer which, Greene says, “enables us to isolate and assess muscle torque and strength”.

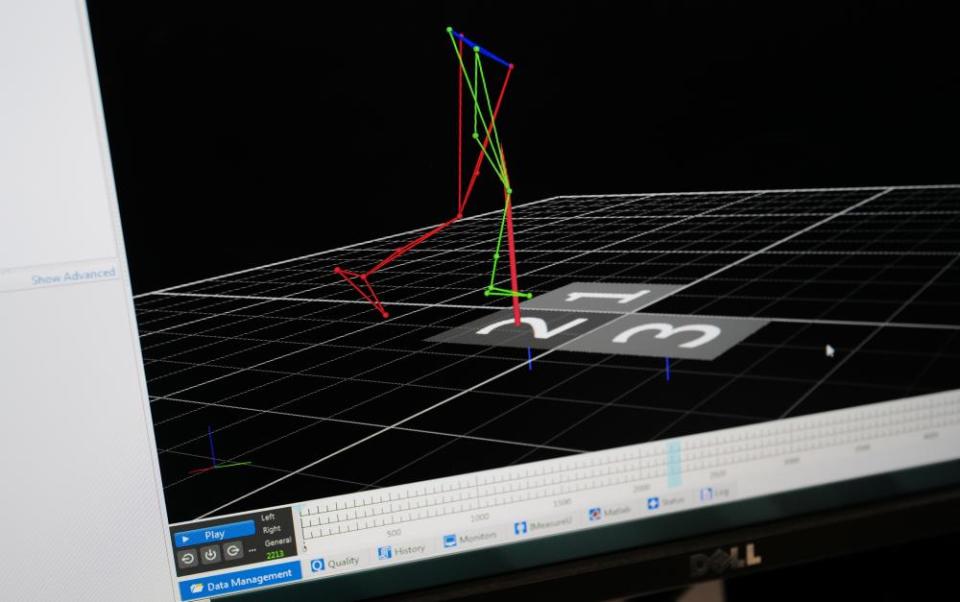

After that reflective markers are taped along Rafferty’s hips, knees and ankles. When she steps into the middle of a room lined with cameras around the ceiling’s perimeter, a three-dimensional reconstruction of the lower half of her body moves across a computer screen.

“Infrared cameras track markers on specific anatomical landmarks which we then use to reconstruct the limbs,” says Greene. “In conjunction with the markers we measure the force. We have two force platforms, which measure whatever happens as you land on them. So, by having the motion data, which is called kinematic data, and having the force data, which is called kinetic data, we’re able to do a series of calculations which lets us work out, for example, how much force is going through a particular joint, what the net action of the muscle is around the joint.”

This way they can see what the knee is doing in a way the naked eye cannot. Greene needs more players and teams involved to strengthen the study. “If you could get a couple of teams to commit to this from the pre-season, through the season, with relatively little involvement, that would be perfect,” Greene says.

“As Claire says: if you’re a female with professional football as a career option, then is 20 minutes to half an hour, an hour, two hours, an afternoon, worth it?

“Successful at reducing ACL injuries and ACL incidents while maintaining or improving athletic performance,” he reads off the Weir paper. “I mean, is that not what we want to do?”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport