Interview, Nelson Vivas: From Arsenal kicking machine to Estudiantes gaffer – and a lot more in between

Some people just end up being in the right place at the right time. “My life in football has been full of many very unlikely moments – I’m just about getting used to it now,” chuckles Nelson Vivas a day after being named Argentina’s manager of the year in his debut season at Estudiantes. “The nicest thing about football is that you never know what will happen next – even the most unexpected things can take place.”

That’s certainly been the way of it throughout a career full of some fantastic tales – and that’s before you get to him leading his current club to the top of the league, a spot in the Copa Libertadores and an epic 21-match unbeaten run, all with a previously unfancied squad.

Long before Gilberto Silva or Alexis Sanchez, Vivas became the first ever South American player to put pen to paper at Arsenal – not that he’s particularly well remembered in north London. Still, he won 39 caps for Argentina and was part of the squad that travelled to the 1998 World Cup, playing the full 120 minutes of his country’s penalty shootout victory over England. He played with everyone from Tony Adams to Diego Maradona, via Gabriel Batistuta, Dennis Bergkamp and the Brazilian Ronaldo.

Vivas is also among the very few men to have played for both Boca Juniors and River Plate, and has been managed by Manuel Pellegrini, Arsene Wenger, Hector Cuper and Daniel Passarella, not to mention Argentina’s three most renowned bosses of the modern era: Cesar Menotti, Carlos Bilardo and Marcelo Bielsa. He later acted as Diego Simeone’s right-hand man at Estudiantes, River and San Lorenzo, coaching the likes of Juan Sebastian Veron and Radamel Falcao.

In the last 20 years, Vivas has somehow managed to be on hand to witness some of football’s most iconic moments, biggest games and most important coaching revolutions. He has often been the common man who just so happened to be strolling through the background.

This is a man with more than a few stories to tell, and he has invited FourFourTwo to his current workplace to share them.

Making memories

The former right-back welcomes us to his first-floor bunker, a near-empty room with artificial grass, red-and-white walls and a few windows that overlook a football pitch and a forest. The room, which is sometimes used for physiotherapy, features just the one object: a chair. It’s clearly a place he comes to for some quiet time.

“I like this place because I can see the players’ lodge,” Vivas says as he looks out across his domain. “It was there, when I was 21 years old, that I came for a trial but ran away after two days. I just went home.”

The aforementioned career looked impossible for a man who had reached the age of 21 without having played a professional match.

“After I quit Estudiantes, I talked with my father and decided that football was not for me. I decided it would be better for me to study. I also worked with my uncle, a blacksmith, and spent 14 months on duty with the military. But then I went to have a final trial at Quilmes, and just a few years later I was playing alongside Diego Maradona at Boca Juniors, then facing England at the World Cup.”

His most vivid memory of that titanic tussle is the moment Argentina’s keeper Carlos Roa saved David Batty’s penalty – and not just because it put the Albiceleste through to the quarter-finals. “That moment was a mixture of joy and a relief for me, because I was down to take the sixth penalty,” he laughs. “Not many people know about that, but I would have taken the first sudden-death penalty.

“Michael Owen was really difficult to stop,” Vivas adds, puffing out his cheeks as he recalls the chastening experience of facing the rapid 18-year-old. “I’ve got a picture showing my ankle completely bent as I tried to stop him. Fortunately, I’ve always been a little bit elastic. As a kid, I would jump from the roof of my house and land on my feet. It is one of the reasons why I was good at headers despite being 5ft 5in, and also an explanation to why I don’t have knee cartilage anymore!”

Impressed by Arsene

Bar the lack of knee cartilage, Vivas – now a 47-year-old – still appears to be in perfect shape. The only noticeable difference from his playing times is the rebellious beard he’s recently sprouted.

“I’ve taken some weird decisions during my career, perhaps based on my lack of experience. Things that I’d never do now, like leaving Boca to join a Second Division Swiss team when I was aiming to be with the World Cup squad at the end of the season.”

Yet that move – to unheralded Lugano – turned out to be a good one. “We won the league and I played every game. I must have impressed [Argentina manager] Passarella, because he then had me man-mark Ronaldo at the Maracana. We won 1-0, which is still Argentina’s most recent win there, and I had earned my place in the team for the World Cup. It was then that Arsenal knocked on my door.”

A competent right-back who also excelled as part of a three-man defence, Vivas still recalls his first meeting with forward-thinking Gunners boss Wenger: “Once Argentina were out of the World Cup, I met Wenger in a restaurant in Paris. It was a very strange situation because I didn’t speak English, so he only talked to my lawyer, and I was sat there not knowing what either of them were talking about!”

Recently, Javier Mascherano congratulated Vivas via Twitter for an interview in which he said, among other things, that winning should not be the only measure of football success, as a manager should be able to see the broader picture. This was most likely a philosophy that was developed at Arsenal, where he made 71 first-team appearances (although just 30 starts) between 1998 and 2001.

“Arsene Wenger was a total manager, not just taking care of tactics, but of every little thing,” Vivas recalls fondly. “It has been years since I have been there, but I could still tell you, with pinpoint accuracy, the whereabouts of everything at the club’s training ground, which Arsene carefully designed right down to the tiniest detail.”

Vive la révolution

Of course, the late ’90s were a time of great change in English football. Nowhere more so than at Arsenal, where Wenger’s squad was full of old-school English footballers, and all those old traditions were blended with the French gaffer’s more considered approach. Vivas relished it.

“Having a captain like Tony Adams was incredibly inspiring,” he beams. “After training was over, he would never walk across a pitch to save himself time and effort. Pitches were sacred, only used for playing football, never to just walk across. I have never experienced such feeling of perfection as I did while I was an Arsenal player.”

Those senses of both tradition and discipline have possibly been things that he has since taken with him into his promising career as a football coach.

For a player who never so much as pulled a muscle until he was the grand old age of 35, diet was very important. And that was another area in which Wenger left his mark. “Learning what is best to eat and when it’s best to eat is something that really helps a player,” Vivas says. “Everyone knows this now, but Wenger was once in the minority.”

Still, despite learning so much and feeling so at home at one of English football’s most famous clubs, Vivas didn’t know how to prove he was capable of earning a place in the first XI. “I had to fight Lee Dixon for my place, and I would think: ‘How on Earth am I going to win my spot if there are no practice matches?’ All exercises included the ball, in reduced spaces, four goalmouths, everything precisely timed – something that I had never done before but, again, something that today is very common.

“Now, as a manager, I understand that this is the best way to analyse exactly how a player is doing. But as a player, almost 20 years ago, I didn’t understand how to prove I was good enough for the first team if we never actually played any games. I did not understand that I was part of a coaching revolution, but I was.

“Arsenal still had a backline with a decade of experience – Dixon, Adams, Martin Keown and Nigel Winterburn – but from then on it was mostly foreign players who joined the Gunners. Football was changing rapidly and Wenger was the one who saw it all coming.”

Physical on the pitch

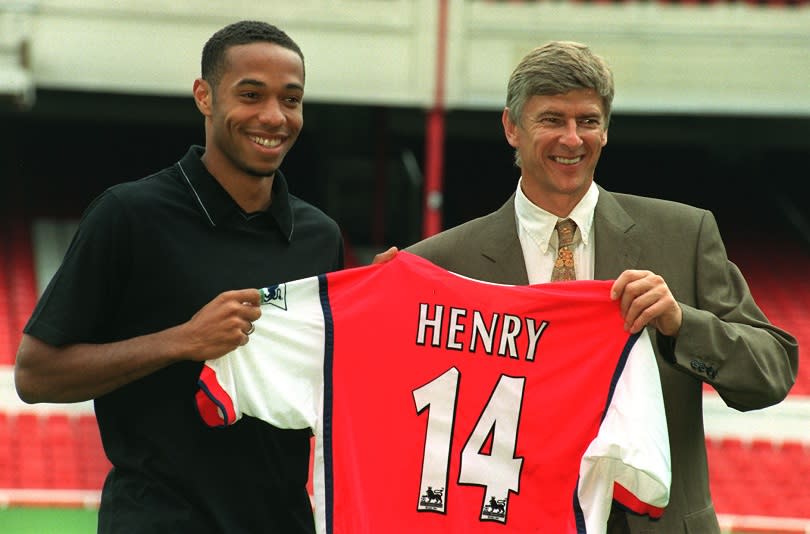

Playing so infrequently in north London was the source of great frustration, and with the risk of his work permit not being renewed, he opted to make a loan move to Celta Vigo. While on a visit to Argentina, Thierry Henry once admitted that during Arsenal training sessions, one of the most dangerous things that a player could ever do was attempt to pull off a one-two against Nelson Vivas.

“That’s true,” Vivas laughs. “You can give the ‘one’ but you’d hardly ever get the ‘two’. I remember Freddie Ljungberg baptised me ‘The Kicking Machine’. I have always done everything to try to win. I’d ask for yellow cards for the opposition players and then inside the dressing room they would nag at me, because that’s a lack of sportsmanship. Even during the training sessions, I got knocks and cuts. Don’t forget the group I trained with had Adams, Keown, Vieira...”

Ex-Quilmes manager Carlos Trullet, when discussing Vivas’s aggressive side, described him as being like “a bag of cats with a dog inside”. That aggression was always a key part of Vivas’s game, but it’s also what made him feel extremely uncomfortable when he entered the Inter dressing room for the first time – it was full of South Americans he had managed to either punch, elbow or kick in continental competitions down the years.

“First I bump into Ronaldo, and I apologise to him for a kick I had given him against Brazil. Then along comes Alvaro Recoba, and I also have to say sorry to him for another incident in a match against Uruguay.”

It was almost as embarrassing during his brief loan period at Celta Vigo when he was talking to one of his new team-mates, Goran Djorovic. “I once played against Argentina in Mar del Plata with Yugoslavia and there was this animal that hit me with a horrific tackle,” the Serbian told Vivas. “Er, that was me,” the defender was forced to reply. “He was right, too – it was a terrible tackle,” he confesses.

Trouble in Buenos Aires

Yet maybe Vivas’s most infamous altercation was one when he did not actually do anything wrong. “People on the streets still come up to me and tell me that I punched Rivaldo – but I didn’t do it,” he insists, correcting a popular fallacy within his homeland.

“We were playing at home against Brazil, we had just conceded a goal, I had just been booked, and then Rivaldo came flying in with a sliding tackle that I just managed to avoid. My instant reaction when he stood up was to punch him. I clenched my fist and started to swing, but I managed to hold it back at the very last moment. I was caught on camera, so lots of people saw,” he says.

This episode is eerily reminiscent to Paolo Di Canio’s near-punch on Winterburn after the Italian, playing for Sheffield Wednesday at the time, had been dismissed for pushing referee Paul Alcock. Of course, Vivas was on the scene, right next to the ref.

“Not long after I had signed for Inter, I was in the lift going up to my new apartment and Rivaldo strolled in – he was playing for Milan. It was just the two of us alone inside the lift. We didn’t say a word to each other. He lived in the same building! One day, I discovered my son playing with a new friend, and it was Rivaldo’s son. Can you believe it?”

Vivas loved the earlier stages of his career in football, but the enjoyment waned as the years passed. “All the people cursing at me left a mark,” he says, with his mind firmly on the abuse he suffered as a former Boca man joining River Plate in 2003.

“That experience was particularly difficult, since the crowd’s patience lasted seconds. I knew those were the rules of the game so I accepted what they said to me, but if someone dared to say anything on the street, even if it was an argument in traffic, I would get out of my car and start chasing the other car on foot. The criticism left me psychologically damaged, I didn’t even dare open any of the papers to see the rating I was getting.”

Overcoming problems

Managing his emotions has often been an issue for Vivas, and he admits to having broken doors in the majority of the houses that he has lived in, generally out of frustration. Vivas hung up his boots in 2003, after his son returned home from school one day with a drawing of the entire family, except his father: it was such a blow that it forced him into retirement. Several days before, he had reacted badly to a nutmeg during a training session and slapped a team-mate. He made a brief return with Quilmes, but then retired permanently in 2005.

Vivas has had some problems taming his demons – particularly since his second retirement from playing. Without the structure of training or any instructions from his coaches, he suddenly found himself with lots of hours to fill, and developed OCD.

“It was probably pretty hard to live with me,” he says. “All the yoghurts in the fridge needed to be organised in a certain way, just like in the supermarket. My clothes were sorted by colour, and all of them folded to exactly the same width. The car always had to be parked with the wheels a certain distance away from the curb, and perfectly aligned with each other. Otherwise I’d pull out and park again and again. I felt frustrated if something was out of place or not in the way I wanted it to be.”

He has since overcome some of these problems with the help of therapy, although some remain. The biggest help perhaps came when Simeone offered him the role of assistant manager at Estudiantes, which has enabled Vivas to once again focus all his obsessions on football; analysing the opponents, planning training sessions and creating tactical systems.

“Simeone jokes that he prevented me from committing suicide, but we were all very obsessive and hard workers and we had a great time,” he says. “I prepared lots of notebooks with annotations. When Diego decided to move abroad, to Catania in 2011, I could not go with him. My daughter was two, I had just divorced and I didn’t want to stop seeing her. What he has managed to achieve with Atletico Madrid has been remarkable. He is undoubtedly one of the best managers in the world at the moment.”

Success in the dugout

The first time Vivas branched out on his own in management, at Quilmes, it ended rather badly – and very quickly. He punched a fan after his first game, with the scrap caught by television cameras. “It was a fan that had been cursing me for the whole 90 minutes, from behind the fence,” Vivas explains. “So I reacted.”

He was summoned to the club president’s office and then sacked on the spot. “It was a difficult moment,” he reflects. “I was in a bad place, but suddenly everything just clicked. I started reading about meditation, Buddhism, and found the serenity I needed to take the next step. I’m very different now, more serene.”

Last year, Estudiantes sporting director Agustin Alayes offered him the chance to coach the reserves. “With all the managers I’d worked for, and all the experience I had, I thought it was a good way to try to leave a mark on players who were developing.”

One thing led to another and Vivas was soon appointed first-team manager by the club’s president, Juan Sebastian Veron (who returned as a player, aged 41, in December 2016 to fulfil a promise made about executive box sales). “Equilibrium is a word that I am using quite a lot. It is the word I would tattoo on myself if I had to pick one. Equilibrium means not getting over-excited when you win, not feeling a tragedy when you lose, being able to cope with the team’s problems and issues with serenity. Equilibrium is not trying to impose your ideas, but to convince the players to apply them. It’s a negotiation. Sometimes you have to give in.

“I’m learning. It’s an honour to be compared with Diego Simeone, Mauricio Pochettino and [current River Plate boss] Marcelo Gallardo – all players of my generation – but I’m remaining balanced; I’m only starting. In Argentina, you win one football match and are told you are the best, but then you lose one match and are forced to believe that you are the worst,” he says, underlining exactly why he is not getting overly carried away with his early success.

After everything he’s seen in the game, Vivas could be forgiven for being happy that, at last, the stories are about him.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2017 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport