The kick that killed a career: the sorry decline of France star Reynald Pedros

Words: Ben Lyttleton and Cedric Rouquette

France and the Czech Republic had gone the distance. After 120 draining and ultimately goalless minutes, their Euro 96 semi-final – played at Old Trafford mere hours before England faced Germany at Wembley – was set for the inevitable conclusion: a penalty shootout.

Les Bleus had defeated the Dutch 5-4 on penalties in the previous round at Anfield, when each of their five kickers made no mistake. The tie was won when Bernard Lama saved from Clarence Seedorf.

France kicked first against the Czechs, and once again every one of their five men scored. Zinedine Zidane, Youri Djorkaeff, Bixente Lizarazu and Vincent Guerin all found the net. So did Laurent Blanc, wearing No.5 and taking penalty No.5, although his effort was weakly hit and almost saved, the ball squeezing under Czech keeper Petr Kouba.

Every time France scored, the Czechs responded in kind. First Lubos Kubik, then Pavel Nedved, Patrik Berger, Karel Poborsky and Karel Rada – all five converted. So, after 10 kicks and with the shootout score tied at 5-5, it went to sudden death.

Promising start

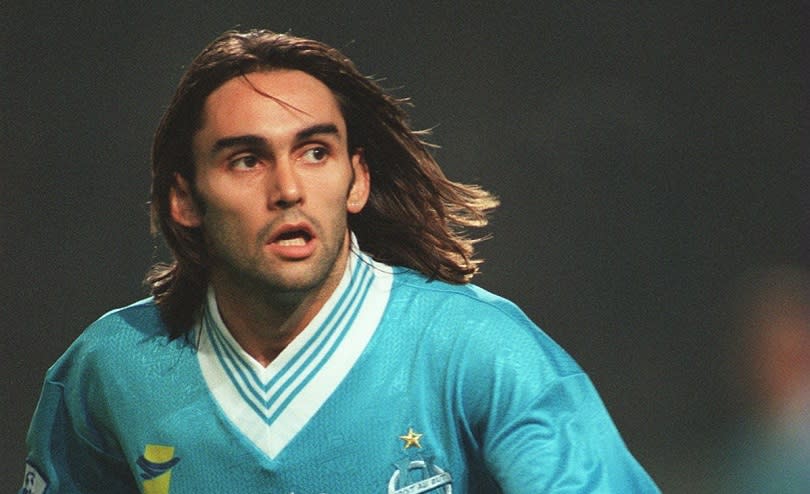

Up next for France was 24-year-old midfielder Reynald Pedros. He'd joined Nantes at the age of 14, then worked his way through their academy to make it to the first team under the fabled Coco Suaudeau, who instigated ‘jeu a la nantaise’ – a fluid style of one-touch attacking football that would culminate in Nantes winning Ligue 1 in 1995. Pedros played on the left wing and, alongside Patrice Loko and Nicolas Ouedec, was part of the ‘trio magique’ that would routinely destroy defences.

Pedros had a role in one of the most memorable goals in French football history, scored by Loko in August 1994 against PSG. Running in from the wing, Loko exchanged a volleyed one-two with Pedros on the edge of the area and then smashed home a stunning goal, without the ball bouncing once. The following season, Nantes reached the Champions League semi-finals, losing to eventual winners Juventus 4-3 on aggregate.

Pedros played for France Under-21s and then the seniors; in fact, he was on the pitch for France’s lowest moment, the World Cup qualifier against Bulgaria in 1993 in which they conceded a late goal that prevented them from going to the United States. Strangely, 5ft 8in Pedros was meant to be covering the post at the corner from which Emil Kostadinov scored Bulgaria’s opener.

By the time Euro 96 came along, Pedros was seen as part of French football’s exciting future. With a World Cup on home soil just two years away, there was an enormous buzz about a group of players that included Zidane, Djorkaeff, Christophe Dugarry and Pedros, Nantes’ 24-year-old star.

Stepping up to the plate

Yet the fierce competition for places at the tournament meant Pedros wasn’t quite top of les Bleus’ pecking order. He played half an hour as a substitute against Bulgaria in the group stage, and 40 minutes of the quarter-final against the Netherlands. Pedros had put himself forward as the sixth kicker against the Dutch, not that he was required, and did the same having come on after an hour against the Czechs – even though one of his team-mates wasn’t so sure about the idea.

“I was surprised to see Reynald go to take a penalty,” said Guerin. “I thought a more experienced player would be taking that kick. I almost told him to come back, but hey, you can’t say that to a player – he’s the one who has made the decision to go.”

Pedros saw it as his responsibility. Although he didn’t regularly take penalties for Nantes, he was a technical player and practised them in training. “I was focused, thinking: ‘There’s no need to rush’ – there was no anxiety at that moment at all,” Pedros tells FFT over coffee on a sunny Parisian afternoon 20 years later.

“I knew I had to make a decision, so I made one. I decided to aim to the goalkeeper’s left, as I had done on the few previous occasions I was asked to take a penalty.”

It was a decision that would prove costly, and – incredibly – mark the beginning of the end of Reynald Pedros’ career.

Fateful kick

Pedros was left-footed, so aiming to the goalkeeper’s left means kicking to his natural side – something most players who aren’t regular penalty takers tend to do. The problem, explains Pedros, was “the technical execution”. He’s right: after a slight stutter in his run-up, he took a poor penalty.

“There just wasn’t enough power,” the 44-year-old admits. “It was too central, and not very high. But then, if the goalkeeper had gone the other way, nobody would have mentioned it. He made the right decision.”

Pedros looked lost after the kick was saved. He ruffled his hair, then lifted his shirt over his head so he wouldn’t see his team-mates’ reactions. After all, the Czechs hadn’t missed any of the 19 penalties they’d taken in major tournament shootouts up until that point. Miroslav Kadlec stepped up next, and smashed his kick straight down the middle. Bernard Lama, who dived early, had no chance.

“When that went in,” Pedros remembers, “I just thought: ‘Shit. It’s all over’. I don’t remember any bad words from my team-mates, though. No one had a go at me.”

In fact, one of the coaches, Philippe Bergeroo, took him aside in the dressing room to cheer him up. “There are worse things than this that happen in life,” he said. Coach Aime Jacquet felt sorry for Pedros, and blamed himself for putting the relative novice in that position.

Pedros thought about the French penalty just before his; the one taken by Blanc. It was in almost exactly the same spot as his, but Kouba failed to stop it. “Five centimetres the other way,” he says. “That’s where fortune comes in.”

Barcelona calling

Pedros may not have had Zidane's status in France at the time, but he was on the way up. He'd won the league title. He'd reached the Champions League semi-finals. He'd played almost an hour for his country in the European Championship semi-final. And then he missed that penalty. Just like that, his career went in the totally opposite direction.

After he’d stepped down following France’s World Cup heroics at home in 1998, Jacquet said Euro 96 had, in his eyes, been preparation for that tournament. He was assessing the players, working out the best combinations and personalities for what would prove to be France’s first World Cup triumph. None of the players had the same thought. Pedros had other things on his mind – mainly his future.

He'd decided to leave Nantes that summer and wanted to find his next club before Euro 96 began. Monaco had been first to make him an offer. He said yes. But then president Jean-Louis Campora told the French press of the interest and said: “I don’t know if it’s a good idea – I don’t know if he’s the right fit.” Pedros phoned the coach, Jean Tigana, and said he didn’t want to make the move. Tigana told him to ignore the president’s comments – “That’s just the way he is,” he said – but Pedros didn’t feel wanted.

Barcelona were the next club to come in for the midfielder. They made a clear offer, but Pedros’ wife didn't want to go to Catalonia, preferring instead to stay in France. “I said no to Barcelona for family reasons,” he says. “I tried to convince her but she would not change her mind. I should have gone there.”

There was a Plan C available to him, however. Marseille were back in Ligue 1 after their relegation caused by the Bernard Tapie bribery scandal two years previously. Sports director Marcel Dib and coach Gerard Gili both wanted him. “We are going to build a big team to get back into Europe,” Gili told him. Pedros went for it. Now, he says: “I think it would have been better if I'd broken my leg.”

Misadventure in Marseille

Pedros was on holiday after the European Championship when he got a call from Gili saying he needed to come back and join the squad early. He went, but was immediately surprised at the lax training sessions. While at Nantes he'd had personalised training regimes to get the best out of him. “At Marseille,” he says, “I barely worked: no pain; no real effort.”

He kept his place in the France team, but only in the short term. Pedros played against Mexico in Paris and was whistled every time he touched the ball. Either he couldn’t hear it or he blocked it out, because he has no recollection of it happening. When one of the backroom staff said to him after the game: “That reaction to you – it’s just not normal”, Pedros had to ask what he was talking about. “I couldn’t believe it was all about the penalty,” he laments. “As far as everyone else was concerned, including myself, it was old news.”

Pedros’ last appearance for France came against Denmark in November 1996. He brought his Marseille form to les Bleus. He understood why he was dropped, but hoped that things would improve at Marseille and that he could force his way back in.

The side were meant to compete for Europe, but ended up closer to the relegation zone. The big names the club had promised would join Pedros never materialised. The supporters made their displeasure quite clear, and the pressures off the pitch affected performances on it. Within six months, Pedros wanted out.

And so began an itinerant career packed with choices that never quite worked out. The player who had Barcelona knocking at his door in the spring of 1996 ended up playing for eight different clubs in four different countries over the next eight seasons.

La dolce vita

In January 1997, Pedros moved to Parma in Italy (by this stage, he had split up from his wife so was free to move abroad). He had to get used to tougher training sessions: from a friendly one-hour workout with Marseille to an intense two hours at Parma. He liked the atmosphere there and the squad was strong, featuring Gigi Buffon, Hernan Crespo, Fabio Cannavaro, Roberto Sensini and Dino Baggio. He became good friends with Lilian Thuram and Daniel Bravo, who is now his punditry colleague on French TV station Canal+.

Thuram gave Pedros some advice that he struggled to get his head around. “When you are in the box in a good position, you just have to shoot,” the defender told him. “Your team-mates will never pass to you even if you’re in a better position, so you should do the same.”

That wasn’t in Pedros’ nature. “Unbearable” is the word he uses to describe that attitude. “To think only of myself on the pitch would be to deny my true self,” he says. “If someone is in a better position, I make the pass.”

As well as the different mindset, Pedros’ body wasn’t used to the change, either. He tore a thigh muscle, limiting his appearances. Parma finished the 1996/97 Serie A season in second place, and Pedros returned for the final three matches of the campaign – just in time, in fact, to be one of the 40 players summoned for France coach Aime Jacquet’s end-of-season get-together. In Tignes, Jacquet announced that his World Cup selection would be based on players who were playing regularly for their clubs.

Pedros wondered what that meant: “If I’ve played one game out of three, is that enough? Does it need to be every game?” At the beginning of the next season, he spoke to the Parma coach Carlo Ancelotti about his situation. The Italian said he couldn’t promise a game every week, but would find a loan deal to a club that would play him: Napoli. “It’s just what you need,” said Ancelotti, “and they have a fierce crowd who will love you.”

He couldn’t have been more wrong.

The Napoli coach didn’t want Pedros; nor did the sporting director. “It was a catastrophe,” the Frenchman sighs. “In two months there, I didn’t play a single game.” The Partenopei changed coach twice, five new players came in, and Pedros just watched it all unravel.

Nowhere like Nantes

That winter, Lyon came in for him, and Pedros accepted the offer. Only after that agreement did he speak to Jacquet about the move. The France manager said he would allow Pedros to have some medical tests with the national team doctors, but saw his return to France as a failure. Pedros knew then it would be hard to force his way back into contention. He at least played regularly for Lyon, but was never called back into the France squad.

“I made all that effort for nothing in the end,” he recalls now. “It was hugely frustrating.”

Part of the problem for Pedros was that his education at Nantes was so unique that wherever he went after working with Coco Suaudeau was going to be a step down: “When I was at Nantes, I didn’t realise how different things would be away from there.”

Nantes taught him to be altruistic; to prioritise the collective above the individual. But it only really worked at Nantes. The standard was much higher with the France team, of course, but nowhere else was he able to recreate that collective team ethic.

“Sometimes,” he says, “I think Nantes gave me a bad education by teaching me those qualities – but it’s still the football that I love. That was the peak, and it came very early to me. I thought it would also be like that everywhere else. I didn’t understand that it could be so different at other clubs.”

Regrets, he's had a few

After Lyon, Pedros played for clubs lower down the French ladder – Montpellier, Toulouse, Bastia – and then, as age and injuries took their toll, he saw out his playing days at Maccabi Ahi Nazareth in Israel and Al-Khor Sports Club in Qatar.

A few years ago, Pedros wrote a book about his experiences, called Le Complex Canari (Nantes’ nickname is the Canaries). “I know where I failed and where I succeeded, but my book is an attack against the system of football,” he said in an interview. “You have to stop believing that everything is rosy just because you play football for a living. Behind every failure there’s an explanation – and it’s not always a sporting one.” He mentions his regrets: turning down Barcelona before the European Championship in England, and that injury at Parma.

And what about the penalty and its legacy? He could surely sympathise with Didier Six, who's claimed that his penalty miss in the 1982 World Cup semi-final loss to West Germany was one of the reasons why he was never entrusted with a managerial role in France. Pedros took amateur coaching jobs when his playing career finished, at Saint-Jean-de-la-Ruelle and Saint-Pryve Saint-Hilaire, and often spoke of his wish to return to Nantes in a coaching capacity.

It never happened. For Pedros, opprobrium over that fateful penalty came briefly from the fans, but he rarely felt it from within the game. It cannot be compared to the fate of David Ginola, who was singled out for blame after that World Cup qualifying home defeat by Bulgaria in 1993.

Putting it behind him

There is one exception to that, however. Marcel Desailly, who was playing in that match against the Czech Republic, was talking about his France memories on a Canal+ documentary called Les Yeux dans les Bleus. Desailly warned about the dangers of taking big penalties: “Just look at Pedros – he missed a penalty and we never saw him again.”

“I don’t like to waste time on things that are not worth it,” is Pedros’ response. “I’m proud that I took the penalty, because it was my duty. So when you hear something like that, you know your family and friends will be more upset than you. For me, it made me laugh. Now I am a pundit on Canal+ and when I see someone miss a penalty, I can talk about the technique, the psychology – everything.

“The others say I am an expert, and it’s true. The guy who craps himself when he’s asked to take a penalty – he shouldn’t be saying anything at all. It’s not a problem for me. I know who my friends are.”

The Euro 96 penalty miss may have started a dramatic career slide for Pedros, but it was not the sole cause of it. Some bad decisions, some bad luck, a few injuries and a unique and unrepeatable football education all contributed to the change in direction – though, in his eyes, his remains a football career to be proud of.

However, it does remind us that for every young superstar that comes along, there are hundreds more who, if a certain goalkeeper happened to dive the other way, could have joined them. Pedros doesn't think about that any more. “For me,” he says, “what’s important is the human side – the emotions and your feelings. That’s more important than whether the ball goes in or not.”

This feature originally appeared in the July 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport